The common understanding is that, setting air resistance aside, all objects dropped to Earth fall at the same rate. This is often demonstrated through the thought experiment of cutting a large object in half—the halves clearly don't fall more slowly just from having been sliced into two pieces.

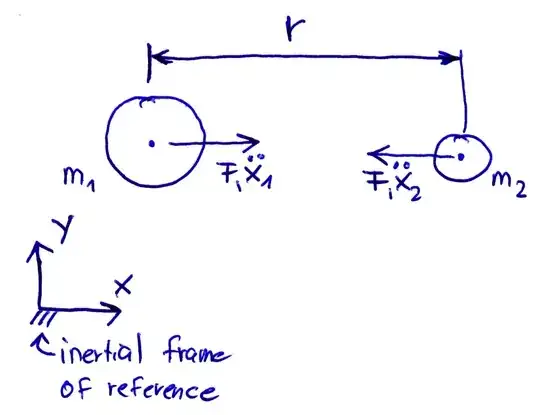

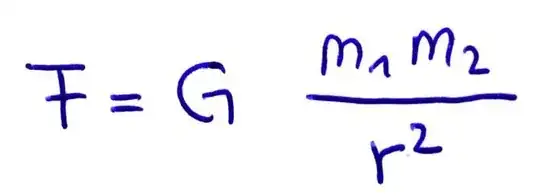

However, I believe the answer is that when two objects fall together, attached or not, they do "fall" faster than an object of less mass alone does. This is because not only does the Earth accelerate the objects toward itself, but the objects also accelerate the Earth toward themselves. Considering the formula: $$ F_{\text{g}} = \frac{G m_1 m_2}{d^2} $$

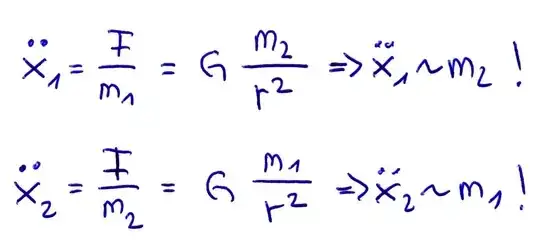

Given $F = ma$ thus $a = F/m$, we might note that the mass of the small object doesn't seem to matter because when calculating acceleration, the force is divided by $m$, the object's mass. However, this overlooks that a force is actually applied to both objects, not just to the smaller one. An acceleration on the second, larger object is found by dividing $F$, in turn, by the larger object's mass. The two objects' acceleration vectors are exactly opposite, so closing acceleration is the sum of the two:

$$ a_{\text{closing}} = \frac{F}{m_1} + \frac{F}{m_2} $$

Since the Earth is extremely massive compared to everyday objects, the acceleration imparted on the object by the Earth will radically dominate the equation. As the Earth is $\sim 5.972 \times {10}^{24} \, \mathrm{kg} ,$ a falling object of $5.972 \times {10}^{1} \, \mathrm{kg}$ (a little over 13 pounds) would accelerate the Earth about $\frac{1}{{10}^{24}}$ as much, which is one part in a trillion trillion.

Thus, in everyday situations we can for all practical purposes treat all objects as falling at the same rate because this difference is so small that our instruments probably couldn't even detect it. But I'm hoping not for a discussion of practicality or what's measurable or observable, but of what we think is actually happening.

Am I right or wrong?

What really clinched this for me was considering dropping a small Moon-massed object close to the Earth and dropping a small Earth-massed object close to the Moon. This thought experiment made me realize that falling isn't one object moving toward some fixed frame of reference, and treating the Earth as just another object, "falling" consists of multiple objects mutually attracting in space.

Clarification: one answer points out that serially lifting and dropping two objects on Earth comes with the fact that during each trial, the other object adds to the Earth's mass. Dropping a bowling ball (while a feather waits on the surface), then dropping the feather afterward (while the bowling ball stays on the surface), changes the Earth's mass between the two experiments. My question should thus be considered from the perspective of the Earth's mass remaining constant between the two trials (such as by removing each of the objects from the universe, or to an extremely great distance, while the other is being dropped).