I've seen this claim made all over the Internet. It's on Wikipedia. It's in John Baez's FAQ on virtual particles, it's in many popular books. I've even seen it mentioned offhand in academic papers. So I assume there must be some truth to it. And yet, whenever I have looked at textbooks describing how the math of Feynman diagrams works, I just can't see how this could be true. Am I missing something? I've spent years searching the internet for an explanation of in what sense energy conservation is violated and yet, I've never seen anything other than vague statements like "because they exist for a short period of time, they can borrow energy from the vacuum".

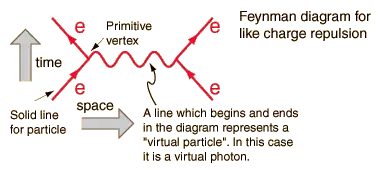

The rules of Feynman diagrams, as I am familiar with them, guarantee that energy and momentum are conserved at every vertex in the diagram. As I understand it, this is not just true for external vertices, but for all internal vertices as well, no matter how many loops deep inside you are. It's true, you integrate the loops over all possible energies and momenta independently, but there is always a delta function in momentum space that forces the sum of the energies of the virtual particles in the loops to add up to exactly the total energy of the incoming or outgoing particles. So for example, in a photon propagator at 1-loop, you have an electron and a positron in the loop, and both can have any energy, but the sum of their energies must add up to the energy of the photon. Right?? Or am I missing something?

I have a couple guesses as to what people might mean when they say they think energy is not conserved by virtual particles...

My first guess is that they are ignoring the actual energy of the particle and instead calculating what effective energy it would have if you looked at the mass and momentum of the particle, and then imposed the classical equations of motion on it. But this is not the energy it has, right? Because the particle is off-shell! It's mass is irrelevant, because there is no mass-conservation rule, only an energy-conservation rule.

My second guess is that perhaps they are talking only about vacuum energy diagrams, where you add together loops of virtual particles which have no incoming or outgoing particles at all. Here there is no delta function that makes the total energy of the virtual particles match the total energy of any incoming or outgoing particles. But then what do they mean by energy conservation if not "total energy in intermediate states matches total energy in incoming and outgoing states"?

My third guess is that maybe they're talking about configuration-space Feynman diagrams instead of momentum-space diagrams. Because now the states we're talking about are not energy-eigenstates, you are effectively adding together a sum of diagrams each with a different total energy. But first, the expected value of energy is conserved at all times. As is guaranteed by quantum mechanics. It's only because you're asking about the energy of part of the superposition instead of the whole thing that you get an impartial answer (that's not summed up yet). And second... isn't the whole idea of a particle (whether real or virtual) a plane wave (or wave packet) that's an energy and momentum eigenstate? So in what sense is this a sensible way to think about the question at all?

Because I've seen this claim repeated so many times, I am very curious if there is something real behind it, and I'm sure there must be. But somehow, I have never seen an explanation of where this idea comes from.