Consider two positive quantities $b>0$ and $c>0$ with associated "small errors" $\delta b>0$ and $\delta c>0$, and

$$a(x) = \dfrac{b+x \delta b}{c-x \delta c}$$

where $x\in(-1,1)$ is an extra parameter that works as a sort of "bookmark": $x$ keeps track of the "small" elements in the expression, namely $\delta b$ and $\delta c$. In which range do we expect $a(x)$ to vary? The minimum is for $x=-1$ (minimize the numerator and maximize the denominator!) and the maximum is for $x=1$:

$$

a_m = \dfrac{b- \delta b}{c+ \delta c} < a(x) < \dfrac{b+ \delta b}{c- \delta c}=a_M

$$

To the linear order in $x$ (we can do this despite the fact that $x$ is not necessarily small because $x$ bookmarks the small errors!), we have

$$

a(x) \approx \dfrac{b}{c}+x \dfrac{c \, \delta b + b \, \delta c}{c^2}+ O(x^2)

$$

In the above expression, $O(x^2)$ means that we stop the expansion before quantities like $(\delta b)^2$, $(\delta c)^2$, $ \delta b \,\delta c $ appear. In this approximation, $a_m$ and $a_M$ still correspond to $x=- 1$ and $x=1$, so that

$$

a_m \approx \dfrac{b}{c}- \dfrac{c \, \delta b + b \, \delta c}{c^2}

\qquad \qquad

a_M \approx \dfrac{b}{c}+ \dfrac{c \, \delta b + b \, \delta c}{c^2}

$$

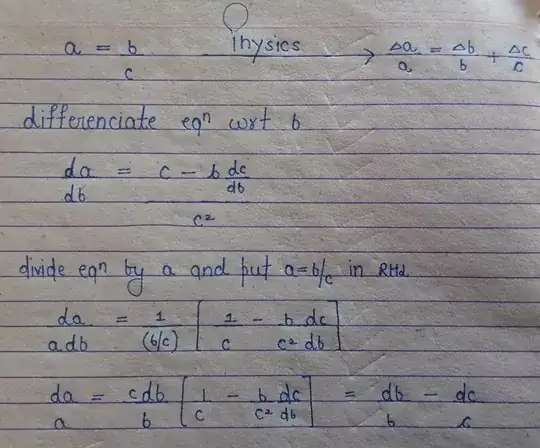

In the end, we obtain the expression for $\delta a>0$ by considering the half-distance between $a_m$ and $a_M$:

$$

\delta a = \dfrac{a_M-a_m}{2}\approx \dfrac{c \, \delta b + b \, \delta c}{c^2} = \dfrac{ \delta b}{c} + a \dfrac{\delta c}{c}

\quad \Rightarrow \quad

\dfrac{\delta a}{a} \approx \dfrac{ \delta b}{b} + \dfrac{\delta c}{c}

$$

Extra: You may use the same method to justify the error propagation for the product $a=bc$ by considering

$$a(x)=(b+x \delta b)(c+x\delta c)$$

for $0<\delta b <b$ and $0<\delta c <c$. Again, $a_m=a(-1)$ and $a_M =a(1)$ and $\delta a =(a_M-a_m)/2$. The formula to the linear order in $x$ is the same as the one for the quotient discussed above, see this.

Important note: The theory of propagation of uncertainty and the (more advanced) uncertainty quantification provide a better (statistical) justification for this simple result, as well as its validity range.

"Quadratic" approach (see the comments) - Given a random variable $X$ that is a linear combination of other two random variables, e.g. $X=sY+rZ$, we have that (see this for the proof or Wikipedia):

$$

Var(X) = s^2Var (Y) + r^2Var(Z) + 2sr Cov(Y,Z)

$$

where the covariance is: ${Cov}(Z,Y) = {E}\left[ (Z-{E}[Z]) (Y-{E}[Y]) \right]$.

Now, if $X=f(Y,Z)$, we can use the above formula if we take the linear approximation $dX \approx \partial_Y f dY + \partial_Z f dZ $: we have that $s=\partial_Y f$ and $r=\partial_Z f$.

The deviations $dX$, $dY$, $dZ$ are legit random variables: $dX= X-f(E(Y),E(Z))$, $dY=Y-E(Y)$, $dZ=Z-E(Z)$, where $E$ denotes the expected value. Moreover, $Var(X+c)=Var(X)$ for any constant $c$, so that $Var(X)=Var(dX)$. the same is valid for $Y,Z$.

In the end:

$$

Var(X) = Var(dX) \approx (\partial_Y f)^2 Var(Y)+ (\partial_Z f)^2 Var(Z) + 2 (\partial_Y f)( \partial_Z f) Cov(Y,Z)

$$

We can apply this formula to $a=bc$ (the case $a=b/c$ is analogous): $c$ plays the role of the random variable $X$ and the values $a,b$ are realizations of the random variables $Y,Z$. We also assume that $Y,Z$ are independent (so their covariance is zero). Therefore, $f=bc$, $\partial_bf=c$, $\partial_cf=b$ (for consistency, these derivatives are formally calculated at the observed/expected value) and

$$

Var(a) \approx b^2 Var(c)+ c^2 Var(b)

\qquad

\Rightarrow

\qquad

\dfrac{Var(a)}{a^2} \approx \dfrac{Var(c)}{c^2} + \dfrac{Var(b)}{b^2}

$$

You may be surprised to see that the result is quadratic, but this is not mysterious: Why is propagation of uncertainties quadratic rather than linear?. As said, the simple prescription discussed in the first part of this answer is just a convenient approximate way of estimating the expected interval in which the variable $a$ can vary.

Better estimation of the variance of $X$ can be given by considering the algebra of random variables.