@JMLCarter's answer is what would be expected of you at your academic level, I guess, but I have to warn you that your formula is actually incorrect if you are serious about probability and statistics.

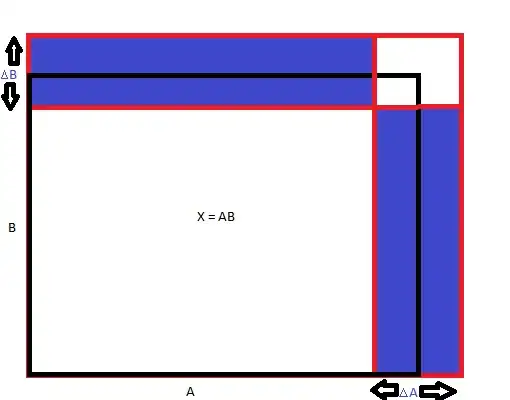

Why probability and statistics, you may ask? Because in a lot of practical applications, $A$ does actually not represent a single value but a random distribution of values, what you would get by repeated measurements. You can then define a mean value $\newcommand{EE}[1]{\langle #1 \rangle} \EE{A}$ and we also need to define how the values are spread about that mean value, which will give us a way to measure the uncertainty. This is done by looking at the mean value of the square of the differences to the mean: $V(A)=\EE{(A-\EE{A})^2}$, a quantity called the variance of $A$. Then the uncertainty you seek is just the square root of the variance: $\sigma_A = \sqrt{V(A)}$, or conversely the variance is the square of that uncertainty. So your $\Delta A$ is my $\sigma_A$, etc. $\sigma_A$ is called the standard uncertainty of $A$ by the way. We define similar quantities for $B$ and $X$.

I will assume a very important condition: that $A$ and $B$ are independent, i.e. that whatever is the source of error for one does not influence the other. This has an important consequence: the mean of $AB$ is just the product of the means (i.e. there is no "interference" between $A$ and $B$), or mathematically.

$$\EE{AB}=\EE{A}\EE{B}.$$

Thus the variance reads

$$V(AB) = \EE{(AB-\EE{AB})^2}=\EE{(AB-\EE{A}\EE{B})^2}.$$

Then, we have the awesome trick:

$$AB - \EE{A}\EE{B} = \EE{A}\EE{B}\left[\left(\underbrace{\frac{A-\EE{A}}{\EE{A}}}_{\displaystyle\delta_A}+1\right)\left(\underbrace{\frac{B-\EE{B}}{\EE{B}}}_{\displaystyle\delta_B}+1\right)-1\right]

=\EE{A}\EE{B}\left[\delta_A + \delta_B + \delta_A\delta_B\right]. \tag{I}

$$

We will then assume that $\delta_A$ and $\delta_B$ are small. Such a statement makes sense since their mean values is 0. We can therefore allow ourselves to neglect the term $\delta_A\delta_B$. We square:

$$(AB - \EE{A}\EE{B})^2=\EE{A}^2\EE{B}^2(\delta_A^2+\delta_B^2 + 2\delta_A\delta_B)$$

and take the mean,

$$V(AB)=\EE{A}^2\EE{B}^2\left(\frac{V(A)}{\EE{A}^2}+\frac{V(B)}{\EE{B}^2}\right),$$

exploiting the fact that $\delta_A$ and $\delta_B$ are independent since $A$ and $B$ are so, and therefore that $\EE{\delta_A\delta_B}=\EE{\delta_A}\EE{\delta_B}=0$.

Finally, we get

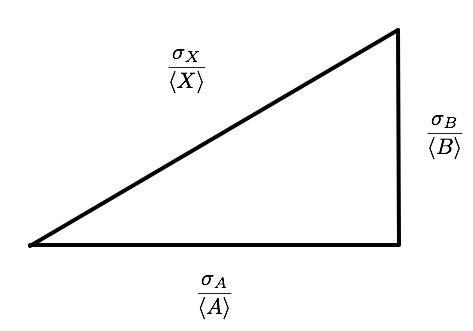

$$\frac{\sigma_X}{\EE{X}} = \sqrt{\left(\frac{\sigma_A}{\EE{A}}\right)^2+\left(\frac{\sigma_B}{\EE{B}}\right)^2}\tag{II}$$

This is actually the correct formula as per the laws of statistics. So how much does it differ from your naive formula? You can see it on the following diagram.

You are basically replacing Pythgoras theorem with: the hypothenuses is the sum of the two other sides. Well, we have the triangular identity

$$\frac{\sigma_X}{\EE{X}} \le \frac{\sigma_A}{\EE{A}} + \frac{\sigma_B}{\EE{B}}$$

So at least the naive formula gives an upper bound: you find an uncertainty for $X$ which is guaranteed to be bigger than the correct one, which is fortunate!

Addendum: since the question was marked as a duplicate, I should at least try to add to the previous answer. We can compute $\sigma_X$ exactly without neglecting anything. Let's restart from eqn (I): we square without neglecting anything and get

$$(AB - \EE{A}\EE{B})^2=\EE{A}^2\EE{B}^2\big(\delta_A^2+\delta_B^2 + 2\delta_A\delta_B + 2\delta_A^2\delta_B + 2\delta_A\delta_B^2+\delta_A^2\delta_B^2\big)$$

and then take the mean value, using the fact that $\delta_A$ and $\delta_B$ are independent,

$$\sigma_X^2 = \EE{A}^2\EE{B}^2\big(\EE{\delta_A^2}+\EE{\delta_B^2} + 2\underbrace{\EE{\delta_A}}_0\EE{\delta_B} + 2\EE{\delta_A^2}\underbrace{\EE{\delta_B}}_0 + 2\underbrace{\EE{\delta_A}}_0\EE{\delta_B^2}+\EE{\delta_A^2}\EE{\delta_B^2}\big).$$

Thus we finally get

$$\frac{\sigma_X}{\EE{X}} = \sqrt{\left(\frac{\sigma_A}{\EE{A}}\right)^2+\left(\frac{\sigma_B}{\EE{B}}\right)^2+\left(\frac{\sigma_A\sigma_B}{\EE{A}\EE{B}}\right)^2}$$

thus adding a corrective term to the previous eqn. (II). And that is the fully correct formula without any approximation whatsoever.