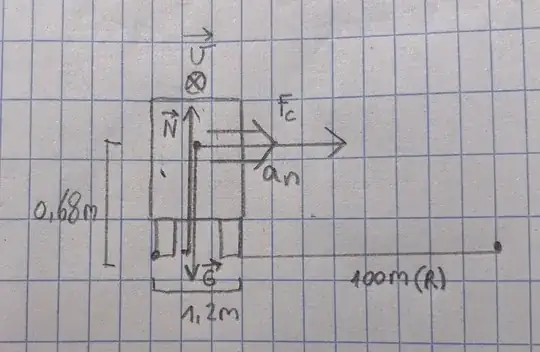

I'm studying for my first engineering exams and i'm a bit stuck on a problem. I have eventually found the answer but I don't understand it completely. I have to find the speed at which a car is going to flip over while cornering. (details in picture). I've drawn a free body diagram and I don't really understand centripetal force. Is it the same as the normal acceleration in a corner (Pointing to the center of the corner)? And how come those are the same (and I never learned anything about centripetal force :))? Also,the centripetal force is the same as the friction force, but why isn't the centripetal force then drawn lowe (where there wheels touch the ground)?

The second question is, how can the car tip over, because both forces (gravitational and cetripetal) are pointing to the same side around the outer tire, creating the same torque (in the wrong direction for tipping it over). I know it's wrong but can't point my finger on it.

- 141

4 Answers

In my physics experience, I have found it more effective to think of it as centripetal acceleration rather than centripetal force. They're incredibly related (through $F=ma$), but I find it is easier to think about what is happening if we remember that it isn't really a force. At best it's a pseudo force.

Centripetal acceleration is a side effect of framing a problem in a rotating frame. Consider two frames. One is just sitting on the side of the road (a nice non-rotating frame). The other is centered on the center of the corner and rotating at a constant rate such that one axis points at the car. The physics for these two systems must be the same. It's the same physical system, so the behavior must be the same. We're just measuring it differently. The numeric values we get when measuring positions/forces/velocities in the different frames will be different, but they correspond to the exact same vectors. Think about a simple example where you are facing East, and there is a cup 3m to your left. It doesn't matter if you think of it as (0m forward, 3m left, 0m up) in your forward/left/up frame or (3m North, 0m East, 0m down) in a frame fixed to the earth in north/east/down. It's referring to the same vector.

We can see that Newton's simple $F=ma$ doesn't work in non-inertial frames such as the rotating frame we described above. If it did, objects would naturally curve through space (they don't... they go in a straight line). The equations of motion in a rotating frame are slightly more complicated. With a little calculus, we find that they include a centripetal acceleration, $F=ma_r - 2\Omega\times v_r$, where $a_r$ and $v_r$ are the acceleration and velocity in the rotating frame and $\Omega$ is the rate it is rotating. That second term is the centripetal acceleration that we are talking about. (There's also Coriolis and Euler effects, but they don't play a part in this particular example, and can be rather confusing at first)

There's a lot of formality here. I've gotten in trouble too many times by not being formal about these things, so it's worth taking the time to realize that this centripetal acceleration is a side effect of thinking about the problem in a rotating frame of reference. Newton's simple $F=ma$ only applies in inertial frames, not rotating ones. The above centripetal correction term is needed to arrive at the correct equations of motion in the rotating frame.

So let's use this frame. In the rotating frame, the car's position is constant. It doesn't change because we picked a rotation speed to make it equal to zero. This simplifies lots of calculations because in this frame, $a_r=0$. With this we see that the sum of all forces must equal the centripetal acceleration. If it were not, the car would not be following the circle perfectly (or would be doing it at a different speed... but we accounted for that by choosing a frame properly).

Because this is a centripetal acceleration, the entire body must accelerate, and that requires a force proportional to its mass. This is why the centripetal effects go through the center of mass. They're really an acceleration of the entire body, and less of a force.

There is only one force in the system which can generate an acceleration in this direction: the force of the road on the car at the tires. Note this is not at the CG. It's on the ground. Its magnitude is exactly that which is needed to achieve the centripetal acceleration needed to stay constant in this rotating frame. There are two remaining forces in the system. There's the force of gravity through the CG (thus not inducing a torque), and there's the normal force of the tire (technically I just split the force of the tire up into its sideways sheering forces and the normal force). If you look at the diagram, these will create torques in opposite directions.

So how does this relate to speed? The faster one goes around the corner, the higher $\Omega$, so the higher the sheer force needs to be to generate sufficient sideways accelerations. At the highest speed possible, the torque generated by this sideways force is equal and opposite to the acceleration of the normal force from the tire.

Now all of this depended on a carefully chosen reference frame that's spinning at exactly the right rate. We could have done the exact same calculations in the inertial frame, using a frame on the side of the road, not rotating. We would come up with the same speed. However, the calculations would look different. There would be no centripetal acceleration, because we are thinking in an inertial frame. However, the car would no longer be at a constant position ($a_r=0$). We now need to pay attention to the fact that the car is following the curve. This will induce a bunch of sines and cosines, and you'll have to use calculus to figure out the right accelerations -- and to show that the magnitude of those accelerations does not change during the corner.

The result will be exactly the same, but it requires higher level math. By carefully choosing our rotating frame to make the problem simpler ($a_r=0$), we are able to sidestep a lot of that extra math. But, in exchange, we need to remember that $F=ma$ doesn't apply in a rotating frame. Corrections are needed. As long as you remember to put them in, a rotating frame can save you tons of calculations.

As an example, consider a problem involving a wheel weight on the tire. In a north/east/down frame on the road, it's motion is a very complicated cycloid. But with a correct frame, moving at the speed of the car and rotating at the rate of the tire spinning, it's position is constant. That means all of the complex math got bundled up into our equations of motion for that frame, rather than in the actual forces and torques. That just makes life easier.

- 53,814

- 6

- 103

- 176

If no forces acted on the truck, it would continue in a straight line at constant speed. Traveling in a circle as shown in your diagram means it is deflected to the right. There must be a force doing the deflecting. The force is perpendicular to the direction of travel, which makes it point toward the center of the circle. That force is the friction of the tires, which should indeed be drawn down low. See Toppling of a cylinder on a block for more on how this force will tip over a truck.

If you hit the brakes as you turn, there is also a component of force backward along the direction of travel. The truck slows as it turns. If you hit the gas, there is a component force forward, and the truck speeds up. If you do neither, the speed stays constant as the truck turns. In that case, the only force is the centripetal force.

See this for pictures of how centripetal force is calculated Direction of centripetal acceleration. It works out the $a = v^2/r$.

- 49,702

This situation is sort of begging to be analyzed in a rotating frame (in which the truck is stationary and you have a fictional centrifugal force). As you have shown it in a non-rotating frame, I will use that method instead.

There are two forces acting on the truck: gravity, which acts through the center of mass, and the force from the road. It is convenient to decompose the force from the road into vertical and horizontal constituents: the normal (equal and opposite to gravity) and friction forces. You are correct that the centripetal force and the friction force are one and the same, and that this force acts at ground level (i.e. the force vector should be drawn at the bottom). As long as the truck does not start to tip, the net torque around the center of mass must be zero. The gravity force provides no torque, so the normal and friction forces must cancel (i.e. their resultant vector points through the center of mass). If you imagine the truck trying the corner a bunch of times, with speed increasing a bit each time, the effective horizontal position of the normal force (where you draw the vertical vector showing upward force from the road) shifts outward a bit each time. When the truck is at its maximum speed before starting to tip, the normal force is at the very edge: all the force is on the outer tire. Thus the ratio of friction to normal forces at this speed is the same as the ratio of the half-width of the truck to the height of its center of mass. From this you can back out the speed.

- 10,037

In order for a car to follow a curve in the road a force towards the inside of the curve must be provided.

As a kid, have you ever tried this game:

There is a sturdy pole, the diameter of the pole is small enough that you can hook it with your hand, and you run in such a direction that as you run past that pole you hook it with your hand. You use that sliding grip to run a very tight corner, maybe even doing a 180 that way.

Or if you don't have a recollection of such activity, you can go ahead and find a pole nearby to try it. For instance, the pole of a street sign.

In order to go around a corner a force-towards-the-inside must be provided, and in the absence of a pole to grab the grip of your feet is all you have to provide that force-towards-the-inside.

The neat thing about grabbing the pole is: your center of mass is high up: closer to your shoulders than to your feet. Hooking that pole is so effective because it obtains the force-towards-the-inside where you need it: close to your center of mass.

All of the above is to explain why in the drawing the arrow marked '$F_c$' is attached to the center of mass of that vehicle. That is where the force-towards-the-inside is needed.

The shorter name for force-towards-the-inside is 'centripetal', from the latin words 'centrum' and 'petere'. 'Petere' means 'to seek'

Centripetal force => center seeking force

About safe cornering speed:

We will assume that the wheels never start skidding sideways.

There is for that vehicle a tipping-over-force: if you push hard enough you can get the vehicle to tip sideways. The wider the wheel basis relative to the height of the center of mass the harder it is to tip the vehicle sideways. Given the width of the wheel basis, and the weight, and the height of the center of mass you can calculate the magnitude of the tipping-over-force.

If the speed of the vehicle through the corner is so large that the required centripetal force is larger than the tipping-over-force then the vehicle will tip over.

Incidentally, that critical speed is not dependent on the weight of the vehicle. For a heavier vehicle the tipping-over force is larger, but the required centripetal force is also larger, in the same proportion.

The critical speed is independent of the weight because gravitational mass and inertial mass are equivalent. We express the weight of an object in terms of gravitational mass, and we express the inertia of an object in terms of inertial mass, and the two are always equivalent.

- 24,617