Filling in some information about limits from Nathan's answer (+1).

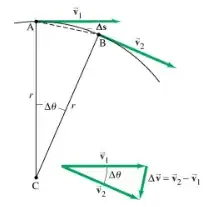

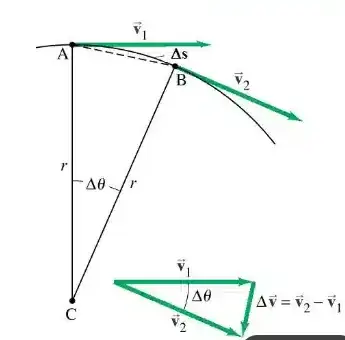

In the diagram, you calculate the centripetal acceleration by using the velocities at A and B. This tells you about the rate of change in velocity over the interval. But you want to know the rate at which velocity is changing at one point somewhere in the interval. All the other points have velocities that are a little bit different. So the answer you get is an approximation.

$$a_{centripetal} \approx \frac{v_B - v_A}{t_B-t_A}$$

You can make it a better approximation by using a smaller interval. How good can you get? Can you get a perfect answer with absolutely no error (assuming perfectly uniform circular motion)?

You can. You look at smaller and smaller intervals that give better and better approximations. You figure out what number the approximations are headed to, and that is the perfect answer.

We can do this for the angle at the base of the isosceles triangle.

Every triangle you look at has an angle $<90^o$. Are the approximate angles headed to $91^o$? No. None of them get as big as $90.5^o$, so they never get to $91^o$. You can apply the same argument to eliminate every number bigger than $90^o$.

Likewise you might ask if they are headed to $89^o$? No. You can pick a slimmer triangle where the angle is $89.5^o$. The approximations go past $89^o$. Again, you can apply a similar argument to eliminate every number $<90^o$.

The only number you can't eliminate is $90^o$.

It would be nice if you could just use a "triangle" with $90^o$ angles. But if you try, A and B are the same point. You wind up with

$$a_{centripetal} = \frac{v_B - v_B}{t_B - t_B} = \frac{0}{0}$$

Taking a series of approximations is forced on you. A derivative handles this for you. It tells you the answer to where are the approximations $\frac{v_B - v_A}{t_B-t_A}$ headed?