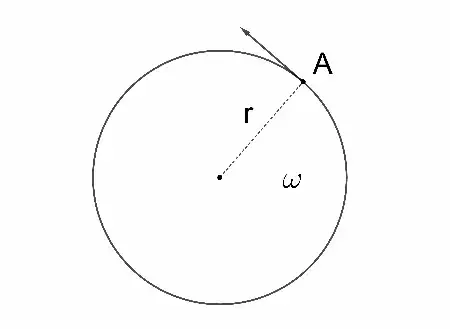

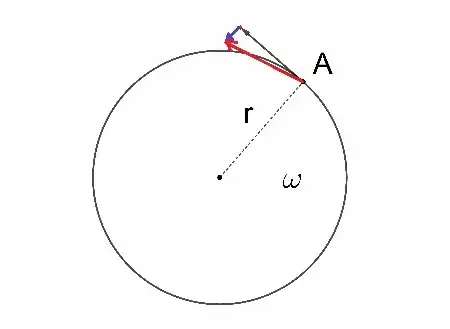

The concern raised in this question, as I understand it, is that we start with a tangential velocity:

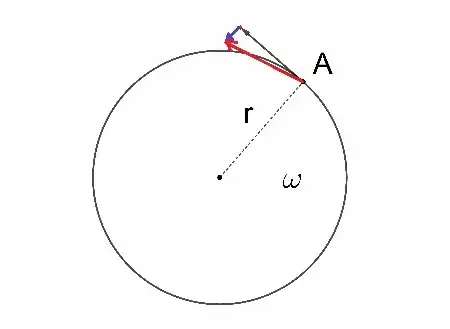

But then, the acceleration, being perpendicular to the velocity, causes the increment $\mathbf{a} \Delta t$ (the blue vector in the diagram) of velocity to be added, thus forming a right angled triangle of vector addition:

This being the case, the concern raised is due to Pythagoras' theorem; the new velocity vector seems to be longer.

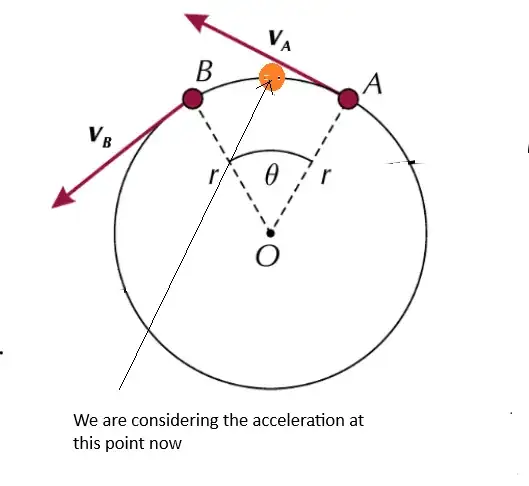

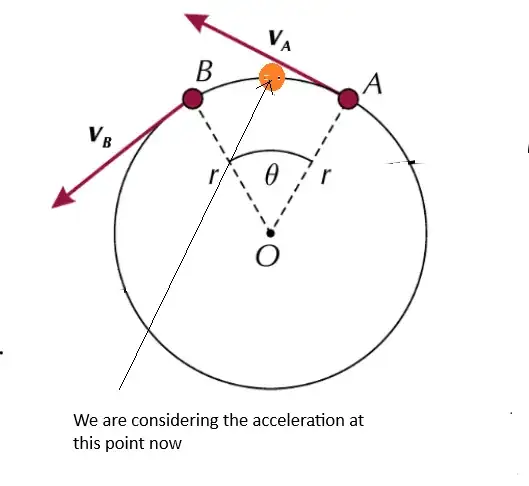

Proper formal proofs (or the argument via work in another answer) can sidestep these problems but in this answer I am attempting to allay the concerns raised about this pictorial/visual argument. Perhaps the best way to do this is to visualise the following situation:

We see in the diagram above that for the moment under consideration, the starting velocity is $\mathbf{v}_A$ and the ending velocity is $\mathbf{v}_B$. Now consider the average acceleration during this short interval. Well, being the average it seems intuitively reasonable to imagine this acceleration being concentrated at the point exactly between point A and point B. Now we have an isosceles triangle instead of a right angled triangle and so the velocity vector does not change its magnitude.

Final comment: Of course, when limits are taken it doesn't matter whether we consider the right triangle or this isosceles triangle. Nevertheless, from an intuitive point of view, hopefully the original poster may find this second visual argument a little more convincing.