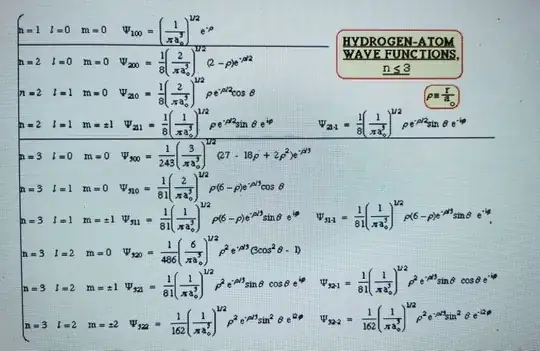

The different probability cloud shapes of the Hydrogen atom (consisting of one proton and one electron) can be solved using the spherical wave function. The answer is often summarized as follows:

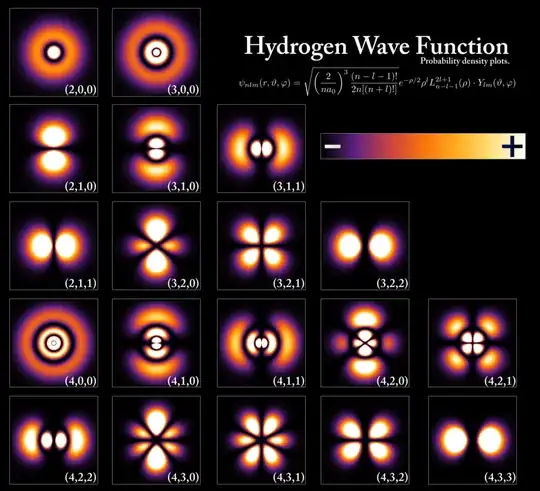

When plotted with 3D graphics, they look something like:

My question is about the direct verification of these "strange" (so to speak) shapes. I have searched and found almost no experimental results that directly verify all these shapes, for example by taking many separate measurements and tabulating the results into a 3D cloud. There is an experiment that purportedly show the (1,0,0) and (2,0,0) and (3,0,0) shape of the probability cloud, but what about the exotic shapes like (4,1,1) and (4,2,0)?

If we show these pictures to a 6 year-old, the first thing they will probably say is: "I don't believe it. Proof it and show me!" Great claims require great experimental proofs. The greater the claim, the greater the burden of proof, right? :)

EDIT: i did read the related post Is there experimental verification of the s, p, d, f orbital shapes? and follow the links given in the answers. It is one experiment where it looks like the top-most (1,0,0) and (2,0,0) and (3,0,0) shapes are reproduced. Unfortunately, only the spherical ones are reproduced, and arguably it would easier to approximately reproduce a general "round" spherical shape compared to a very strange characteristic one like, for example (4,2,0), which if it can be reproduced very accurately is a good omen that the Schrodinger function produces this "shape", as it is not easy to produce this exact specific probability cloud with some other functions...