The fields $\bf E$ and $\bf B$ are the fundamental components of the electromagnetic field. They define the field via its effects, producing a force on a charge $q$:

$$

{\bf f} = q ( {\bf E} + {\bf v} \times {\bf B}).

$$

One can in principle do the whole of electromagnetism using just these fields.

In a material medium (e.g. glass, or a metal, or a semiconductor, or a gas, etc.) these fields are very complicated however. They vary at lot on the distance scale of the atomic spacing, getting huge near atomic nuclei and smaller elsewhere. So most of the time we do not treat the fields at a point, but rather we average over a region of space of the order of a few atomic spacings (e.g. a nanometre in a solid, or a larger region in a gas). This is where other things such as polarization $\bf P$ and magnetisation $\bf M$ come into play. If we divide the charge in any region into the part associated with little electric dipoles (called bound charge) and the rest (called free charge) then we have

$$

q_{\rm tot} = q_{\rm bound} + q_{\rm free}

$$

so the first Maxwell equation reads

$$

{\bf \nabla} \cdot {\bf E} = \frac{q_{\rm b} + q_{\rm f}}{\epsilon_0}

$$

where I used the subscripts $b$ and $f$ for 'bound' and 'free'.

Now a basic result (which can be proved with a little standard manipulation, it is first year undergraduate level) is that

$$

{\bf \nabla} \cdot {\bf P} = -q_{\rm b}

$$

where $\bf P$ is the dipole moment per unit volume, called polarization. So it follows that

$$

{\bf \nabla} \cdot (\epsilon_0 {\bf E} + {\bf P}) = q_{\rm f}.

$$

Well look at that! The right hand side is nice and simple, because it only involves the free charge, and it often happens that we know from the start how much free charge there is. There might even be none at all! (e.g. a light wave travelling in glass in ordinary circumstances). So we choose to give the combination $(\epsilon_0 {\bf E} + {\bf P})$

a symbol of its own: we call it $\bf D$. This is how the field $\bf D$ gets introduced, with its associated equation

$$

{\bf \nabla} \cdot {\bf D} = q_{\rm f}.

$$

The story for $\bf H$ is similar.

First we derive by analysis that the magnetization is connected to the part of the total

current that is caused by little current loops, with other contributions coming from free current and changes in the dipoles. The central result of this derivation is that the total current can be divided up as

$$

{\displaystyle \mathbf {j}_{\rm tot} =\mathbf {j} _{\mathrm {f} }+\nabla \times \mathbf {M} +{\frac {\partial \mathbf {P} }{\partial t}}}.

$$

Next we use this in the fourth Maxwell equation, and we notice that a convenient way to write the equation is to give the combination

${\bf B}/\mu_0 - {\bf M}$ its own letter ($\bf H$) and we arrive at

$$

{\bf \nabla} \times {\bf H} = {\bf j}_{\rm f} + \frac{\partial \bf D}{\partial t}.

$$

Again, this is convenient because often we want to treat problems without worrying about what the magnetisation current and the bound charge is doing.

So, to conclude, fields $\bf E$ and $\bf B$ are the basic fields. (Together they make up a tensor called the field tensor, but you don't need to know that.) Fields $\bf D$ and $\bf H$ are introduced for reasons of mathematical convenience and the associated physical insight. They are particularly useful when thinking about capacitors and inductors and electromagnetic waves propagating in media when the free charge and free current are known.

The other two Maxwell equations do not involve the sources so they are not affected. They are

$$

{\bf \nabla} \cdot {\bf B} = 0

$$ and

$$

{\bf \nabla} \times {\bf E} = - \frac{\partial \bf B}{\partial t}

$$

Note, for example, it is $\bf B$ not $\bf H$ which has zero divergence. So $\bf B$ lines always run in closed loops, but $\bf H$ lines do not need to if there is some magnetization around. In a similar way, if some medium carries no free charge then the $\bf D$ field runs in closed loops (or it may be zero), but the $\bf E$ field might not.

On usefulness

The fields $\bf D$ and $\bf H$ are useful when considering things like capacitors and inductors, but they really come into their own when considering electromagnetic waves in dielectric media. It would be hard work calculating things like reflection coefficients without them. And they also come into their own in the consideration of energy. The energy flow for example is given by the Poynting vector

$$

{\bf S} = \frac{1}{\mu_0} {\bf E} \times {\bf B} - {\bf E} \times {\bf M}

$$

---a rather tricky formula. But how much easier it is in terms of $\bf E$ and $\bf H$:

$$

{\bf S} = {\bf E} \times {\bf H}.

$$

On relative permittivity and permeability

We always have ${\bf \nabla} \cdot {\bf H} = - {\nabla} \cdot {\bf M}$ and

${\bf \nabla} \cdot {\bf B} = 0$. But this means it will often not be possible to write ${\bf B} = \mu_0 \mu_r {\bf H}$, so answers which only

make reference to that formula are missing a major part of the physics.

In particular you usually can't use ${\bf B} = \mu_0 \mu_r {\bf H}$ when thinking about permanent magnets.

In the case of a permanent magnet you have a static case with no free current, so ${\bf \nabla} \times {\bf H} = 0$, which means the integral

of ${\bf H}$ around a loop is zero, but this will not be true for $\bf B$,

so there is no simple proportionality between them.

However, in many simple amorphous media it happens that, at low fields, ${\bf M} \propto {\bf H}$. So in this case ${\bf B}$ is also proportional to ${\bf H}$ so we can introduce the relative permeability $\mu_r$ defined through the equation

$$

{\bf B} = \mu_0 \mu_r {\bf H}.

$$

This is a useful equation, but much more restricted in its validity than the other ones I have written above. (Actually we can also use this result slightly more generally, in non-linear materials where $\bf M$ is not proportional to $\bf H$ but is in the same direction; in this case $\mu_r$ will depend on ${\bf H}$.)

Similarly, simple dielectric media will have polarization proportional to $\bf E$, and consequently $\bf D$ proportional to $\bf E$, so we define a relative permittivity $\epsilon_r$:

$$

{\bf D} = \epsilon_0 \epsilon_r {\bf E}.

$$

But what is the difference between $\bf B$ and $\bf H$ in physical terms?

${\bf B}$ is the field which gives the force on a moving charge, and it is the field which is induced by a changing electric field. It is the one involved in electromagnetic induction. Its integral over a surface is the flux.

$\bf H$ is the field which is easily calculated from a given amount of free current, and the component of $\bf H$ along a boundary does not change when you move from one medium to another (if there is no surface free current). This makes $\bf H$ useful in calculating what electromagnetic waves do, and it is also useful for tracking energy movements via the Poynting vector ${\bf S} = {\bf E} \times {\bf H}$.

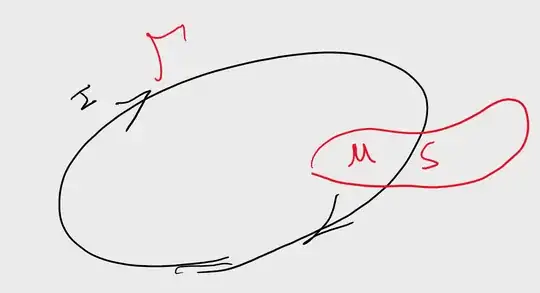

A permanent magnet has $\bf B$ running in loops and $\bf H$ following $\bf B$ outside, but not inside, the magnet, in such a way that its integral around a loop is zero

(unless there is a current flowing nearby), c.f.

Direction of H and B inside and outside a bar magnet

A lump of glass with light waves propagating in it has both $\bf B$ and $\bf H$. If you have an inductor made of a solenoid with a fixed current, then when you slide a piece of glass into the cylinder (keeping the current constant) the value of $\bf H$ does not change but the value of $\bf B$ does. And if you slide in a piece of soft iron the value of $\bf B$ changes enormously. In this case the current supply providing the constant current will do some work, which provides the field energy.

A comment on units and physical dimensions

One of the puzzles of this area of physics is why $\bf B$ and $\bf H$ have different physical dimensions in the SI system of units, and so do $\bf D$ and $\bf E$. One should not hang too much on that. It is just a human choice about definitions. The people inventing the SI system could, with good logic and physical sense, have chosen to introduce the field ${\bf B} - \mu_0 {\bf M}$, giving it the symbol say $\tilde{\bf H}$. Then we would all be learning the formulae

$$

\tilde{\bf H} = {\bf B} - \mu_0 {\bf M}

$$

and

$$

{\bf \nabla} \times \tilde{\bf H} = \mu_0 {\bf j}_{\rm f} + \mu_0 \frac{\partial {\bf D}}{\partial t}.

$$

This way of looking at things has the handy result that $\tilde{\bf H}$ and $\bf B$ have the same physical dimensions, which makes a lot of sense, but it results in a $\mu_0$ in the formula relating $\tilde{\bf H}$ to current and the inventors of the system of units wanted to avoid that. So there we have it.