Polarization rotation due to a polarizer: in the comments I said that a polarizer does not rotate the polarization (a birefringent medium does). It blocks one component, the linear component parallel to its axis. I hold this, but I thought about the following system where a polarization rotation seems to happen due to the action of many polarizers. I never thought about it before, I hope (it's true and) it can help (but sorry, no quantization here, just classical).

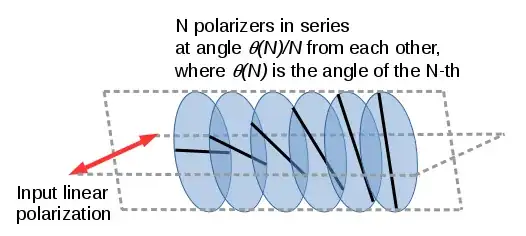

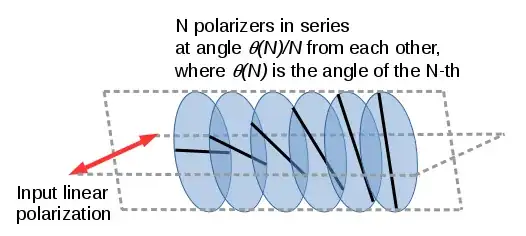

Let's imagine a linear polarization at $0^o$ arriving on a series of $N$ polarizers as in this picture:

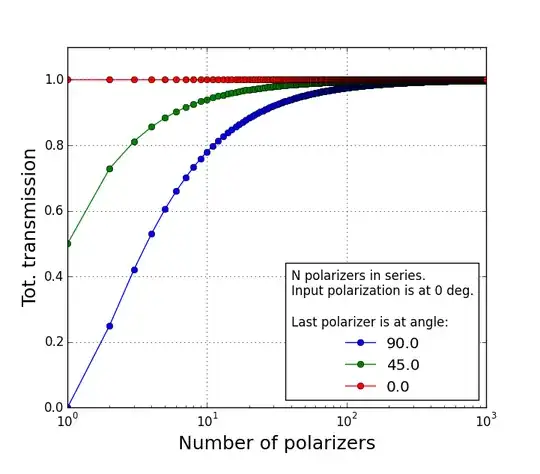

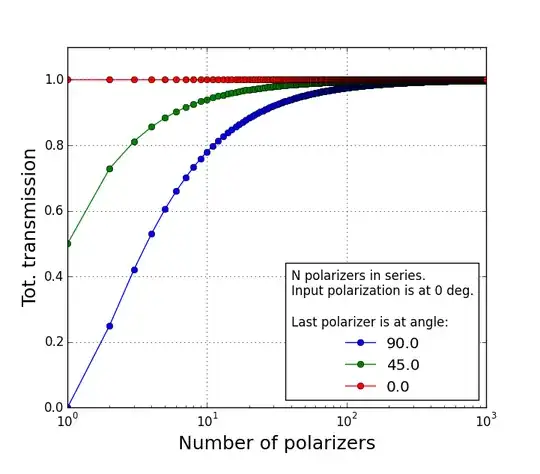

each polarizer is rotated by the same angle with respect to the previous one, so their axis spiral from horizontal up to the angle of the last one ($\theta(N)$, $=\pi/2$ in the figure, but you can choose it). Malus law says that the transmission of one polarizer is $I=I_o \cos^2(\alpha)$, where $\alpha$ is the angle between its axis and its input linear polarization. So the total transmission from the series of polarizers will be $T=(\cos^2(\theta(N)/N))^N$, where we can choose the angle of the last one ($\theta(N)$).

In the next figure I plot $T(N)$ for $\theta(N)=0, \pi/4, \pi/2$. When $\theta(N)=0$, no matter how many polarizers are there, they'll be all parallel and $T=1$ always. For $\theta(N)=45^o$, if there is only one polarizer (i.e. the last one, $N=1$) $T=0.5$. For $\theta(N)=90^o$, if there is only the last polarizer ($N=1$), $T=0$ because it's perpendicular to the polarization.

But in any case, increasing $N$ the transmission goes to 1. So, the polarization is kind of guided by the polarizers, and actually rotates with little losses if $N$ is large. I think this could be what happens in the liquid crystal displays, where the twisted arrangement of the molecules act as the polarizers here.

This is the closest I could think when you mention rotation by a polarizer.