"I just want to know, before entering the slit, the particles had no vertical momentum. But after that, they got vertical momentums. Now, how it proved the Uncertainty Principle? Feynman wrote that as the pattern diffracted, the uncertainty of vertical position i.e. vertical momentum increased. Can you tell me how?"

Let's take the things one by one. Look at the picture in my former answer. From the wave inside the slit, Huygens' principle tells us that every point generates a new spherical wave. You can see this more clearly in the animated picture in the site I indicated above. Now, since the slit is very narrow, what gets out from it? A spherical wave. If the slit were very, very wide, the parallel wave coming to the slit would have exited approximately as a parallel wave, but since the slit is so narrow, the spherical waves emitted from the few points of the wave inside the slit, exit the slit in the spherical form. So, here we have a linear momentum component arising, $p_y$.

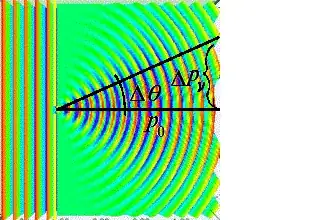

Thus, the wave comes to the slit with linear momentum $p_0$ along the horizontal axis, and this momentum is simply deflected in all the directions, under all the angles $\theta$. So, its direction spreads out. The horizontal component of the linear momentum decreases a bit, $p_x = p_0 cos\theta$ and there appears a vertical component $p_y = p_0 sin\theta$. As long as $\theta$ is very small, $cos\theta ≈ 1$ and $sin\theta ≈ \theta$, s.t.

$$p_x ≈ p_0, \ \ \ \text {and} \ \ \ p_y ≈ p_0 \theta \tag{i}$$.

Until now it's clear?

Now we go to the uncertainty principle, that says similar things, but in a more mathematical form. For our experiment, the principle says,

$$\Delta y \Delta p_y \ge \hbar/2 \tag{ii}$$

The $\Delta$ from a quantity means standard deviation, but I don't want to complicate you with math. It means in short how big is the undetermination of that quantity. In our case, the undetermination in the height $y$ in the particles' position in the slit is the very slit height, which is very small, as you see in my picture, or in the animations in the site I recommended. So, $\Delta p_y$ is quite big,

$$\Delta p_y \ge \frac {\hbar/2}{\Delta y} \tag{iii}$$

To get some approximate idea of how big is $\Delta p_y$, you can see in my picture the height that I denoted by $\Delta p_y$. Again, I don't want to complicate you with math, but behind the slit we can see, at some distance an interference pattern with maxima and minima of brightness. If the distance from the slit is proportional to $p_0$ then the height of the central maximum is roughly proportional to $\Delta p_y$.

Until now is clear?