I was thinking to ask this on Math Stackexchange, but maybe here would be better since I also hope the answers also explain from quantum computation context.

Problem

So I was reading the paper "Concrete quantum-cryptanalysis of binary elliptic curves", and I got stuck in understanding how to construct a multiplication by constant circuit for binary field. In their CHES presentation and their other paper, the authors describe that it is easy to construct the circuit from a matrix since multiplication by constant is just a linear mapping.

On their other paper, they present this matrix as a representation of multiplication by $1 + x^2$ modulo $1 + x + x^4$:

$\Gamma = \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 1 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 & 1 & 1 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $

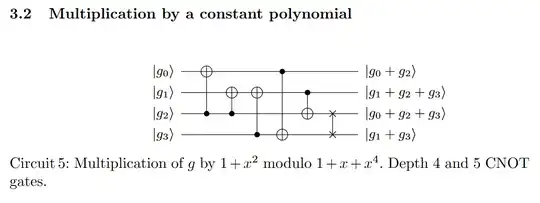

which by LUP decomposition, corresponds to this circuit:

Questions

The questions are interrelated. They are:

1. How to construct matrix $\Gamma$?

2. Why the multiplication matrix is a 4x4 matrix for a 4-qubit circuit? I thought it would be 16x16 $(2^n = 16)$?

3. Is that particular matrix ($\Gamma$) really correct for all values?

My Attempts So Far

For Question 1

My guess is by creating two matrices, e.g., $INPUT$ and $OUTPUT$, which includes all possible inputs and the corresponding output after the constant multiplication. Then, the matrix $\Gamma$ can be obtained from $OUTPUT * INPUT^{-1}$.

I have tried from scratch: calculated all the possible 16 input and the corresponding output pairs (derived from SageMath) and make the mapping (i.e., $\left| x0,x,x^2,x^3 \right> = \left| 0010 \right> \rightarrow \left| 1110 \right>, \left| 0100 \right> \rightarrow \left| 0101 \right>$, and so on...

However, then I realized that the resulting matrix is a rectangular 16x4 matrix rather than a square matrix for each $INPUT$ and $OUTPUT$, so the inversion can not be done when I tried that on Matlab.

For Question 3

For each possible input, I applied $\Gamma$ to verify the output result. While 6 of them are correct, the other 10 are wrong. For example, $\left| 1011 \right> \rightarrow \left| 2231 \right>$ rather than $\left| 0011 \right> $.

I am not sure that kind of paper would contain such errors. So my bet is my approach was all wrong.

I would be very grateful if anyone could guide me on this. Any help is appreciated. Thanks!