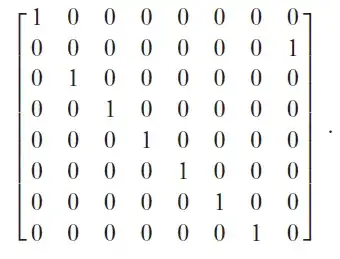

I have been trying to solve this puzzle of constructing this transformation from CNOT and Toffoli gates as mentioned in NC page 193 (Ex 4.27)

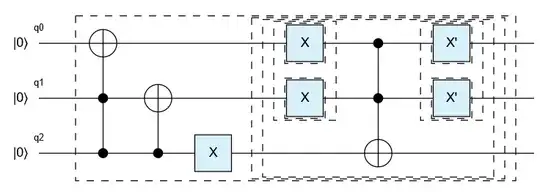

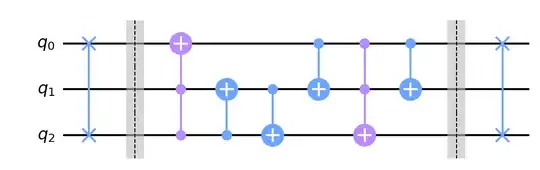

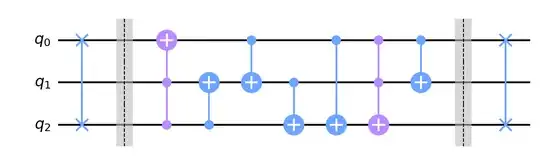

Here is what I have done:

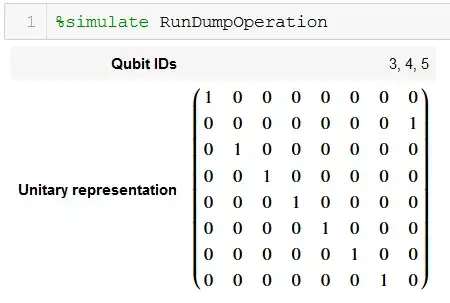

- First observation is it has 8 rows and columns, so it is showing the table for 3 qubits.

- Whenever it is not $|000\rangle$ and $|111\rangle$ it always add 1. $|001\rangle$ becomes $|010\rangle$ etc.

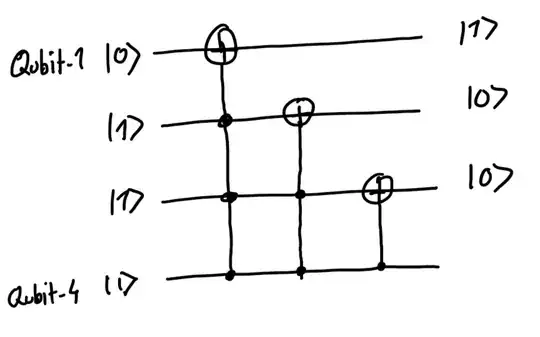

- I ignored the complicated part just tried to implement the easy always add 1 part.

- One observation for $|001\rangle$ to $|110\rangle$ is the LSB qubit is always flipped.

- At this point I realized I would keep one line for $|1\rangle$ and it would help me always flip a state. (let's call it qubit 4)

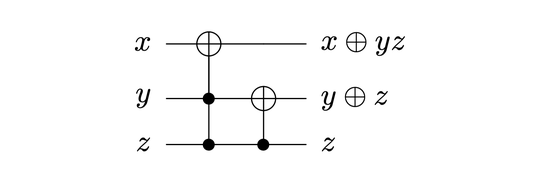

- Then I realize when would qubit 2 and qubit 1 change. Qubit 2 changes when qubit 3 and 4 both are 1. Qubit 1 change when qubit 2,3,4 are 1.

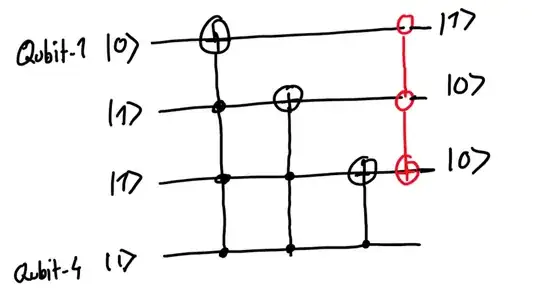

- Then I ran the rest of the two cases and checked what output they generated and brute forced to correct it using Toffoli gates.

Is it possible to verify if this is how the puzzle is intended to be solved or did I miss something?

(Also CCCNOT gate is a feasible gate right? or am I making things up?)