It is indeed an approximation, in particular an approximation that is usually good at high enough temperatures.

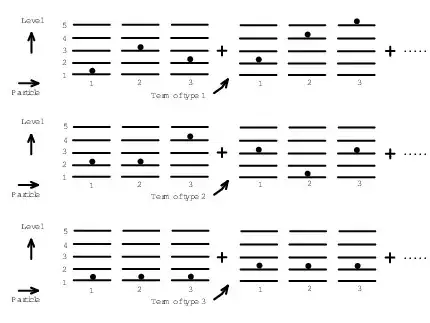

For $N$ distinguishable, non-interacting particles the partition function is $Z(\mathrm{dist.}) = {Z_0}^N$, where $Z_0$ is the single-particle partition function. If the $N$ particles are all in different quantum states then there are $N!$ microstates of distinguishable particles which all correspond to the same microstate of indistinguishable particles. However, if the particles are not all in different states then the number of microstates of distinguishable particles corresponding to the same microstate of indistinguishable particles is less than $N!$.

So in general the relationship between the sum over microstates for distinguishable particles and for indistinguishable particles is quite complex. However, if the temperature is high enough then (for most systems) the number of accessible quantum states will be much larger than the number of particles, so it is unlikely more than one particle will occupy the same quantum state. In this case we can make the approximation that the partition function for distinguishable particles is just $N!$ times that for indistinguishable particles. I.e. $Z(\mathrm{indist.}) = {Z_0}^N/N!$ as you wrote.

The claim that at high enough temperatures the number of accessible quantum states will be much larger than the number of particles is not true for all systems, for example it is false for those with bounded energy spectrum (such as the ideal paramagnet or the example the OP gives). Also, how high the temperature needs to be depends upon the system. For an ideal gas at atmospheric densities it's a good approximation for temperatures much above 1K.

The above is true for quantum particles (Fermions or Bosons). In the classical limit the quantum energy-level separation is taken to zero and the spectrum becomes continuous. For a continuous spectrum the probability that two particles are in exactly the same state is zero, and so the approximation becomes exact in this limit. Note however, that there is no such thing as a classical two-level system, such as the example given by the OP. A classical system with two local minima can in some cases be treated as a two level system, but this is in itself an approximation.