Experimental setup

Think of the following situation: you have two black boxes. One contains a laser that emits photons linearly polarized at an angle of 45° with respect to the horizontal, we label this state $|45^°\rangle$. The other black box contains two lasers, each of which emits photons in one of the two orthogonal linear polarization states which we label $|H\rangle, \, |V\rangle$ for horizontal and vertical. Note that we could also write $|0°\rangle, \, |90°\rangle$ instead. There is another device in this second box that randomly switches between the two lasers so that only photons from either of the two lasers are leaving the box at any given time. We assume that at any given time, we only have a single photon from box 1 or box 2 in our measurement apparatus.

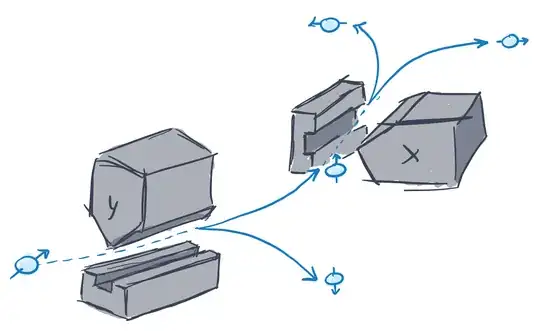

From the outside, the two boxes are identical and the light emitted from both boxes also appears to be identical when you analyze it using a 50/50 polarizing beam splitter (PBS) and two detectors D1,D2. The beam splitter works in this way: if a photon with $|H\rangle$ polarization is incident, it always leaves through output 1 to D1, if a photon with $|V\rangle$ is incident, it always leaves through output 2 to D2. Hence, you can distinguish between the two orthogonal polarizations by observing which of the two detectors D1 ($|H\rangle$), D2 ($|V\rangle$) registers a signal at any given time.

Now lets see the measurement outcomes for the light emitted from either of our two boxes.

Box 1: Since the PBS projects the incoming light into the $\{|H\rangle, |V\rangle\}$ basis. For each single photon, the detection at D1, D2 is random. If we repeat the measurement many times with many single photons emitted from box 1, we will find that the probability for detection at either D1 or D2 is 50%. We can explain this by recalling that the light emitted from box 1 is in the $ |45^°\rangle$ state. In the $\{|H\rangle, |V\rangle\}$ measurement basis of our PBS, this is a superposition state, $ |45^°\rangle_{H,V} = 1/\sqrt{2} \left ( |H\rangle + |V\rangle\right ) $.

Box 2: Now we have a random stream of single photons, each in a well defined polarization state wrt to the measurement basis of the PBS. If we measure again for a large number of single photons, we will find exactly the same result as before, the detection clicks will be evenly split between D1 and D2.

Change of basis

So can we distinguish between box 1 and box 2? Yes, we can simply by introducing a change of basis using a half wave plate HWP. If we insert the HWP in the beam path at an angle of 22.5° wrt to the horizontal axis, linear polarized light $ |45^°\rangle$ will be transformed into $ |H\rangle$ (or $ |V\rangle$ depending on the exact configuration of the HWP - but let's not bother with the exact mechanism here). That is, we rotate the states in the tilted polarization basis $\{|45^°\rangle, \, |135^°\rangle \}$ (or any other pair of orthogonal angles) to align with the $\{|H\rangle, \, |V\rangle \}$ measurement basis of our PBS. Correspondingly, the states of the $\{|H\rangle, \, |V\rangle \}$ basis are rotated into the tilted basis $\{|45^°\rangle, \, |135^°\rangle \}$.

So what happens if we introduce this change for the measurement on box 1 and box 2?

Box 1: Since the state incident on HWP is $\|45^°\rangle$, the photon transmitted through the HWP will always be in $|H\rangle$. Therefore, we will only detect photons at detector D1!

Box 2: photons $ |H\rangle$ will be transmitted as $ |45°\rangle$, $ |V\rangle$ will be transmitted as $ |135°\rangle$ through the HWP. Again, PBS projects the incoming polarization states $|45°\rangle$ or $|135°\rangle$ onto the $\{|H\rangle, \, |V\rangle \}$ basis. The outcome of the projection for both of the two possible input states will be random again - 50% of the time you get a click at D1, 50% of the time at D2. So the measurement outcome for a large number of photons did not change in this case!

What does that mean?

Evidently, the perceived randomness of every single measurement outcome before introducing the HWP between box 1 and box 2 is of different nature. This is because the light emitted from box 1 is in a pure state while the light emitted from box 2 is in a mixed state. We found an unitary transformation of our Hilbert space (rotating our basis by 45° through the introduction of the HWP) that rendered any single measurement outcome for box 1 deterministic whereas the outcome for box 2 remained completely random. In fact, in case of box 2, there is no such transformation that would render the detection deterministic. The randomness in case of box 1 is an inherent feature of the superposition state that we can completely remove by finding the basis in which the state of the system conincides with one of the basis vectors. In case of box 2, the randomness is externally introduced through our device that randomly selects which polarization state of photons is allowed to exit the box.

So not only have we found a simple experimental setup that distinguishes mixed and superposition states by introducing a change of basis, we also learned that superposition is a basis dependent phenomenon.