Firstly, the question refers to the symmetry about particle exchange - the title is confusing, since there are many other important symmetries, starting with $\psi(\pm x)=\pm \psi(x)$, which has to do with the number of nodes in the eigenstates vs. the ground state.

Regarding the particle exchange, the argument given in most quantum mechanics books is that, since the particles are indistinguishable, the physical properties should be independent when we switch any two particles. Wave function is not a measurable quantity itself, but the particle density is. Thus, in a system of two particles we have

$$

\rho(x_1,x_2)=|\psi(x_1,x_2)|^2=\rho(x_2,x_1)=|\psi(x_2,x_1)|^2

$$

(Note that a system of particles is generally described by a single wave function.)

This means that the wave function under particle exchange may acquire a phase factor:

$$

\psi(x_1,x_2)=e^{i\phi}\psi(x_2,x_1).

$$

If we exchange the particles twice, we should return to the initial state (this condition is however relaxed in the case of anyons):

$$\psi(x_1,x_2)=e^{i\phi}\psi(x_2,x_1)=e^{2i\phi}\psi(x_1,x_2),$$

hence $e^{2i\phi}=1\Rightarrow e^{i\phi}=\pm\sqrt{1}=\pm 1.$

I.e., the wave function is either symmetric or antisymmetric in respect to exchange of any two particles (the discussion above is easily generalized to exchanging any two particles among a larger number of particles.)

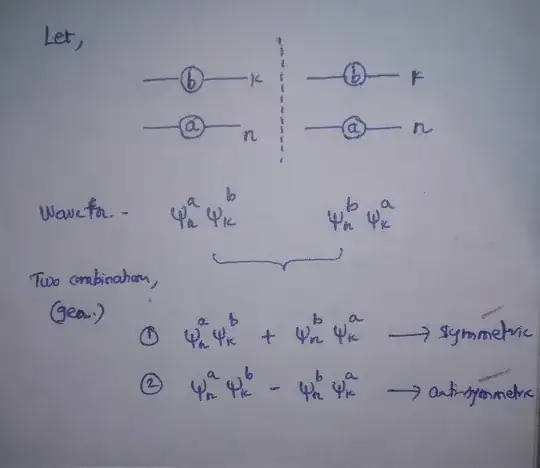

In case of non-interacting particles, the eigenstates of the multiparticle system can be represented in terms of one-particle eigenstates, of which one has to form symmetric/antisymmetric combinations to satisfy the condition derived above:

$$

\psi(x_1,x_2)=\phi(x_1)\varphi(x_2)\pm \varphi(x_1)\phi(x_2).

$$

This is easily generalized to more particles with Slater determinants and permanents.

This innocent game with the phase factor turn out to have far reaching consequences in terms of the particle properties (spin and magnetic moment), their quantum statistics (Bose-Einstein vs. Fermi-Dirac), their interactions, etc.

Related:

Wavefunction of three particles

'Deriving' superposition representations for 3 particles

Why does Hartree-Fock (HF) theory even work?

Why can't you always write the anti-symmetric state as slater determinant?