I can understand that once I fix the velocity of light at $c$, there is a relative variation in space-time based on special relativity (inertial frame of reference). It's not clear to me how Einstein figured out how mass (and hence energy) bends spacetime in an accelerated frame (a non-inertial frame of reference). Was that a guess made by Einstein?

3 Answers

Here is a modern translation of Einsteins' paper on general relativity. http://eotvos.dm.unipi.it/documents/EinsteinPapers/Einstein1911English.pdf

The theory of relativity shows that the inertial mass of a body increases with the energy it contains; if the increase of energy amounts to $E$, the increase in inertial mass is equal to $E/c^2$ , where $c$ denotes the velocity of light. Now, is there an increase of gravitational mass corresponding to this increase of inertial mass? If not, then a body would fall in the same gravitational field with varying acceleration according to the energy it contained. And then the highly satisfactory result of the theory of relativity, by which the law of the conservation of mass leads to the law of conservation of energy, could not be maintained, because it would compel us to abandon the law of the conservation of mass in its old form for inertial mass, but maintain it for gravitational mass.

This must be regarded as very improbable. On the other hand, the usual theory of relativity does not provide us with any argument from which to infer that the weight of a body depends on the energy contained in it. But we shall show that our hypothesis of the equivalence of the systems $K$ and $K'$ gives us gravitation of energy as a necessary consequence.

We have to make a distinction between inertial mass and gravitational mass. Intertial mass is the ratio between force and acceleration as in $F=ma$ and gravitational mass is the scale factor (charge?) in gravitational force, as in $F=G\frac{Mm}{r^2}$.

In his previous work on special relativity, Einstein argued that the inertial mass scales with energy content, which you should recognize in the famous $E=mc^2$. Now, he defines two frames. The frame $K$ is an observer at rest in an uniform gravitational field of acceleration $g$ and $K'$ is an observer accelerating with acceleration $g$ with no gravity present, for example a rocket in space. In both frames it holds true that when you drop an object, which means the only force they experience is gravity, the objects will accelerate towards the floor at $g$.

Now the question arises whether gravitational mass should be equal to inertial mass. In the past this has been experimentally proven and this was an accepted fact at the time. If this is not assumed, we have to abandon conservation of inertial mass. Einstein then shows that if the equivalence principle holds, which says that there is no measurable difference between $K$ and $K'\,^\dagger$, this equivalence of inertial and gravitational mass follows as a direct result. It just pops out of the math! In the paper I linked there is a nice derivation.

If we now assume the equivalence principle holds, this has some big consequences. For example, light has to bend in a gravitational field. Because it also does in the accelerated frame. The only way to fully reconcile this, is to introduce curvature of spacetime. This means that the metric tensor, which is just a 4-dimensional measuring stick, varies over space$^{\dagger}$.

$\dagger$ the equivalence principle is defined for systems that are small enough. This means we can assume the gravitational field is uniform and we can neglect tidal effects. Or put simply, we assume the gravitational acceleration is the same in the bottom of the elevator and the top.

$\dagger\dagger$ The precise definition is more subtle. Whether the metric tensor is constant, changes when you do a change of coordinates. One way to check if your spacetime is curved, is to transport a vector around a loop in spacetime. If the vector is unchanged for all possible loops, you have a flat spacetime. As an example, the surface of the earth is curved. If you move a vector from the equator, to the north pole, to some other point on the equator and finally back to where you started, you will generally have a different vector.

- 19,613

One justification for the curvature of spacetime comes from the Ehrenfest paradox. Although I'm not sure of its historical significance.

The circumference of a rotating disk is less than that of a stationary disk, by length contraction. The radius, however, is unchanged because it's perpendicular to the direction of motion. Then

\begin{equation} \text{stationary:}\;\;\;\;\frac{\text{circumference}}{\text{diameter}} = \pi\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\;\text{rotating:}\;\;\;\;\frac{\text{circumference}}{\text{diameter}} < \pi \end{equation}

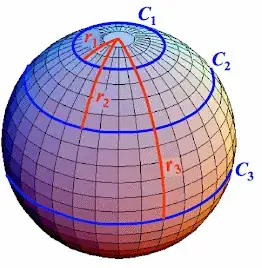

This is a paradox if we think only in terms of Euclidean geometry. In non-Euclidean geometries, this is a common occurrence as illustrated by the 2-sphere:

In the image above $\frac{C_i}{2r_i} < \pi$, and the opposite inequality occurs in hyperbolic (non-Euclidean) geometry.

Therefore, the relativity of rotations (a type of acceleration) requires non-Euclidean geometry. Then gravitational fields, which are indistinguishable from accelerations (by the equivalence principle), also require non-Euclidean geometry.

- 1,920

I found this explanation interesting.

Why can't I do this to get infinite energy?

Light doesn't lose any energy in constant space-time while leaving earth (or in Newton's world, light speed should reduce if gravity were a force, which can't be true based on Maxwell's equations). You need to have a hill in space for the light to lose energy (resulting in a change in frequency), which means space is curved. The newly developed quantum theory (E=hv) should have helped Einstein reach that conclusion.

- 155