I learnt that an optic fibre uses the concept of total internal reflection (TIR) to transmit data at high speed, but why do they not use just simple mirrors instead of using refractive medium and making a light incident at an angle more than the critical angle, so that total internal reflection can occur?

6 Answers

There are essentially two reasons: manufacturability and loss.

Manufacturability

Optical fibers can be mass produced very inexpensively (cents per meter) by putting preforms of different glass materials together, heating on a draw tower, and then drawing out into a long, thin fiber. This process enables making enormous amounts of fiber very rapidly. The resulting fiber is surprisingly strong, and can take a fair amount of abuse with no loss of performance (just don't kink them!).

Conversely making high reflectivity mirrors is much more complex. Surfaces must be extremely smooth and then coated, either in metal or dielectric layers. Then this would somehow have to be drawn into kilometer long tubes, which is not simple to do. All of this must be done without heating the material so much as to destroy the reflective layer and in a way that renders it protected from corrosion. Again, not obvious how this would even be possible, let alone cheap.

Loss

Reflective losses are actually quite high. In the visible to NIR where optical fibers are frequently used, metals like silver or gold are highly reflective, where highly means 96-98% reflective. At that level, roughly half the power is lost after a few dozen reflections. Conversely, with an optical fiber, as long as there is nothing for the total internal reflection to couple into, losses can be extraordinarily low with essentially all of the energy contained in the waveguide. For example, with SMF28 fiber, the loss is less than 0.15dB per kilometer (primarily due to scattering), thus you lose less light through an entire kilometer of fiber than from bouncing a single time off a metallic mirror.

- 469

Microwave waveguides above 10 GHz have an obvious problem. The resistive losses in the waveguide walls*, even if are made of the purest silver or the finest gold alloys, make them practically useless for long distance communications. Besides the nontrivial manufacturing issue as to how to coat without cracks hundreds of miles long flexible glass fiber with a good high conductivity metal, the conductivity at optical frequencies, or even above 10 GHz is just not good enough.

Already at mm-waves, to reduce these inherent losses, the trend is always to apply more dielectrics and less metal except for very short connections. Short is understood and measured here in the number of wavelengths. You can already see this at antenna installations where the transmitter/receiver is placed remotely, to avoid metal waveguides they use dielectric lenses and dielectric guides, if they can.

There have been attempts to reduce those losses by using overmoded waveguides, such as the so-called helical waveguides of Bell Labs, but their prohibitively high manufacturing and installation costs killed all large-scale attempts.

- The "obvious" problem is related to the cross-sectional size of the waveguide, which is on the order of the operating wavelength. As the frequency goes up, the size goes down and thus for a fixed power to be transmitted the field intensity increases.

With increased field intensity the wall currents must also go up, while at the same time the higher frequency reduces the skin depth, increasing the current density and increasing the wall's "$I^2R$" losses.

- 2,348

- 21,193

First, at some wavelengths metal mirrors are used instead of total internal reflection. For example, see this microwave band component: Microwave waveguide E&H-Bend.

But, for visible light, we use optic fibres instead of a scaled-down version of this metal tube. Some good reasons for this are:

1 - Losses. Metals are very lossy, meaning that each time the light pings off the metal, some of its energy is lost into heat. Normal optical fibres still have losses, but they are much lower than they would be with metal.

2 - Cost. This is more speculative, but when I imagine a tiny metal tube, I feel like that is going to be more complicated to make (and more expensive) than optic fibres, which are glass and plastic.

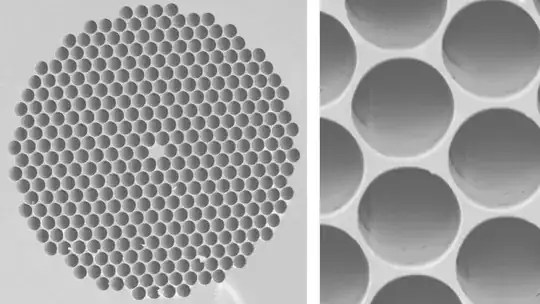

You may be interested in photonic-crystal fibre. These fibres sort of do exploit a mirror to confine the light. However, the mirror is made of a pattern of alternating refractive indices (called a photonic crystal, the pattern in the image below), so reflection at dielectric interfaces is still playing a central role, even if the reflection at each interface is not "total", but only partial.

Photonic-crystal fiber (Wikipedia)

Photonic-crystal fiber (Wikipedia)

These are able to confine the light more tightly than a normal optical fibre. The tighter the light in space (the narrower the beam) the wider it is in the spread of momentum of the light - so more of it is "bouncing" against the sides at a steeper angle. So the ability of photonic crystal fibres to confine light more tightly is related to them gaining more mirroring at steeper angles.

(In the microwave regime, I believe they use metal because few materials have a significant refractive index for light in that regime. But I am not very knowledgeable about microwaves.)

- 2,348

- 1,847

I’m pretty sure it’s because they can’t make a perfect mirror. TIR just allows to not have to deal with making a perfect one. Check Why not regular reflection?

- 411

My memory's hazy, but I understood (high quality) fibre optics to employ Total Internal Refraction instead of reflection. That is, a beam of light inside the fibre that is heading towards the edge is increasingly refracted such that the beam is bent towards the destination and never reaches the side of the fibre (ie. it travels in a curve rather than sharp corners).

The intent here is that the beam never "bounces" off anything - every time it gets close, it's encouraged away by progressive refraction. This also has the effect of reducing the amount of "spread" a pulse of light will show over a long cable, and making the distances a beam travels slightly shorter (although with hair-fine fibres, I don't imagine it makes much difference). Comments correctly note that refraction affects propagation, so beams travelling through the middle of the fibre will still arrive at different times than those taking a less direct path - I believe the windier path is still more similar to direct than a bouncing path, but happy for someone to throw some actual science in to contradict me on that point!

To make such a fibre requires the extrusion of material to be different at the sides than in the middle. This obviously adds to manufacturing costs, and the quality control of such a process is presumably pretty precise to maintain the uniformability over hundreds of metres of fibre.

Cheaper fibres are made of a single grade of material, and so do not have progressive refraction, and instead use the refractive properties of the edges of materials to reflect the beam back towards the opposite side of the fibre. This causes pulses to spread over long fibres, because some beams will be straighter in the cable than others, so will arrive at their destination sooner than the ones that bounced around more. As receivers have got more sensitive and smarter, I don't imagine these issues really matter any more in all but the most demanding use-cases, so cheaper fibres are "good enough" for most uses.

- 137

Another reason besides practicality as other users have mentioned is that the "standard" design of optical fiber allows for a direct treatment using electromagnetic theory, and is rather simple. Simply account for the refractive index as $n=\sqrt{\epsilon_r}$. You can essentially apply the theory of waveguides (dielectric waveguides) to an optical fiber through this

Using a reflective coating seems less obvious to analyse from a theoretical standpoint. You'd have to develop theory for a more particular problem of reflection of waves inside a cylindrical mirror.

- 4,386