I was wondering how does one go about solving for the spin (1/2) eigenstates in an arbitrary direction?

Let me specify my question. I had seen previously (such as Spin operator in an arbitrary direction) how to calculate such a problem when we are given the unit vector in spherical coordinates: ̂=(sincos,sinsin,cos) (which actually makes quite a lot of sense to me).

But, however improper my question may seem, I am quite unsure as to how would I apply this to a general case where I'm simply given any unit vector (not necessarily in spherical coordinates).

For example, let's say we are given a vector, for simplicity, $v= \tfrac1{\sqrt9}(1,2,2)$. What would be the spin in this direction?

Would I simply have to dot product it with the Pauli matrices (with an extra factor of $\hbar/2$) and then solve for the eigenvalues and eigenstates? How would I display this using the z-basis eigenstates (would I simply apply a change of basis?).

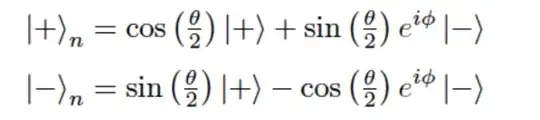

My main confusion seems to revolve around how regardless of where I've searched, all answers seem to be of the form

which, I know how to derive using the spherical unit vector, but am completely confused as to why it would apply to a general unit vector that might not necessarily be described using spherical coordinates.

I'd greatly appreciate any guidance or assistance.