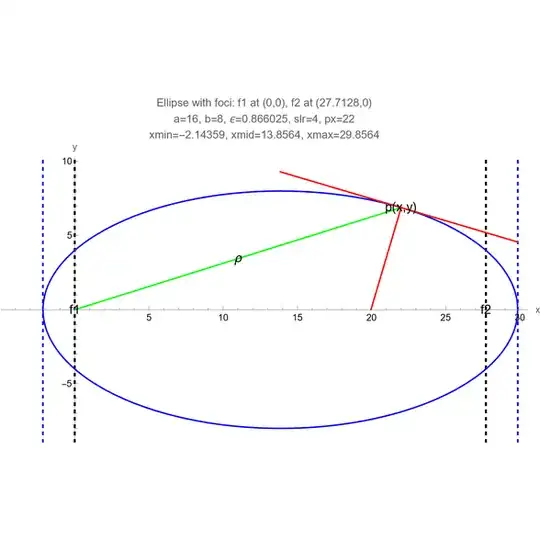

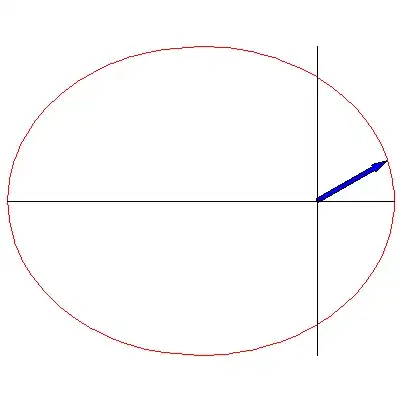

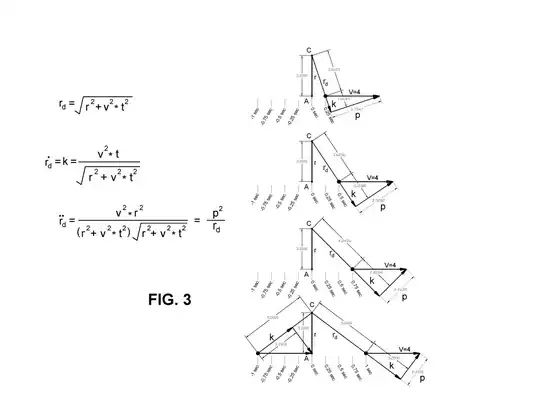

Consider a planar, elliptical orbit in a simplified two body, $\frac{K}{r^2}$ central attractive force problem (i.e. assume $m1 >> m2$ so focus $f1$ is effectively at $m1$, with $m2$ at point $p\left(x,y\right)$) and $\rho$ being the radius (green line) from $m1$ to $m2$ ($f1$ to $p\left(x,y\right)$), as indicated in the following plot ($f1$ at coordinate origin, periapsis at left blue hash, apoapsis at right blue hash):

I am trying to determine the expression for (what I am referring to as) the radial velocity $v_\rho=\frac{d\rho}{dt}$ along the direction of $\rho$ toward $f1$, at each point $p\left(x,y\right)$ on the orbital ellipse, strictly as a function of $\rho$. To be clear, I do not seek the expression for the velocity tangent to or normal to (red lines in plot) the orbital ellipse at point $p\left(x,y\right)$, but rather only the velocity along $\rho$ toward $f1$.

I have tried to come up with this expression using the very illuminating discussion in this item How do we describe the radial velocity in elliptical orbits?, but with no success yet. I also thought this might be readily found in a classical mechanics text (e.g. Symon), but haven't found (or recognized) such.

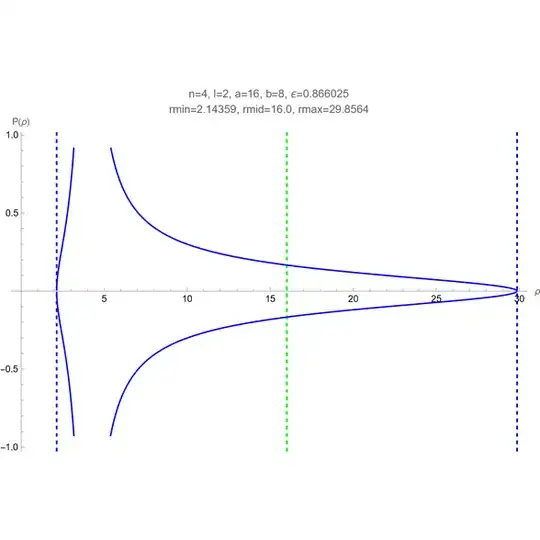

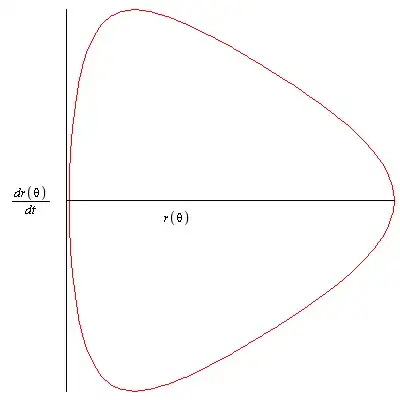

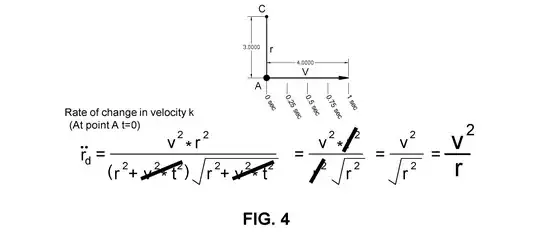

In line with How do we describe the radial velocity in elliptical orbits?, I expect the plot of this radial velocity to be structurally similar to the following but with a continuous, finite value - unlike the infinity exhibited in this plot - for the latus rectum at $\rho=4$ (note that $\dot{\rho}=0$ for periapsis at $\rho\approx+2.14359$ in the plot below, which differs from periapsis at $x\approx-2.14359$ in the elliptical orbit plot above):

Any reference to an existing solution, or advice on deriving one, would be greatly appreciated.

I think I have provided enough information to fully characterize the problem, but can certainly provide more info if I've missed something.