The answer is in general negative, but it is technical.

If there existed such a Hilbert basis, by construction, the basis would be included in the domains of the Hermitian operators $X$ and $P$.

As a consequence, they would be symmetric as and they would admit selfadjoit extensions given by the standard selfadjoint operators $X$ and $P$ in $L^2(R)$ up to a unitary transformation. This transformation is the one that sends the basis into the standard basis of Hermite functions in $L^2(R)$.

The obstruction is now that it is possible to define operators $X$ and $P$ which satisfies the usual CCR on a common subspace of their domains (and this is equivalent to your CCR for the associated $a$ and $a^\dagger$), but such that there are *no" selfadjoint extensions for $P$.

Tipically, $X$ and $P$ defined on $L^2([0,+\infty))$ as the usual differential operators with common domain given by the space of smooth functions which smoothly vanish at $x=0$.

It is however possible to add some hypotheses to yours to prove your assertion.

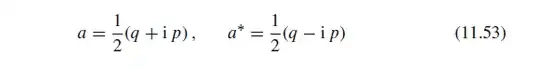

In particular, the operator $a^\dagger a$ must be essentially selfadjoint on its domain and there must not exist dense invariant subspaces under the action of $a$ and $a^\dagger$. That is an alternative formulation of the Stone von Neumann theorem.

A more rough set of assumptions which guarantee the validity of your assertion is the following one.

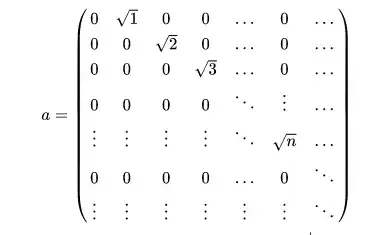

There exists a vector $\psi$ in the domain of $a$ such that $a\psi=0$.

The domain of the two operators includes an invariant subspace which, in turn, contains $\psi$.

The space of finite linear combinations of the vectors $(a^\dagger)^n \psi$ is dense in the Hilbert space.