This question actually has a very easy and rigorous answer. Having which-path information "available" is just a crude way of saying that the system is correlated with anything else. Usually, this is because the system has been decohered in whatever basis corresponds to the possible paths, which is usually position basis. In your case, the photon is actually never put into a coherent local superposition, and so interference will not be seen. Instead the SPDC process essentially creates a Bell state where one photon is thrown away. Skematically, the situation you describe is as follows. The splitting process is

$\vert S \rangle \otimes \vert I \rangle \to \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \Big [ \vert S_L \rangle \otimes \vert I_L \rangle + \vert S_R \rangle \otimes \vert I_R \rangle \Big ] = \vert \psi \rangle \qquad \qquad \qquad (1)$

where $S$ and $I$ stand for the signal and idle photons, respectively, and $L$ and $R$ stand for the left and right path. The reduced state of the signal photon is

$\rho^{(S)}=\mathrm{Tr}_I\Big[\vert \psi \rangle \langle \psi \vert \Big]$

(If you don't know what $\mathrm{Tr}$ means, or what a density matrix is, you absolutely must go learn about them. It doesn't take that long, and is crucial for understanding this question.) The measurement performed by the apparatus is essentially a measurement in the basis $\{ \vert \pm \rangle = \vert S_L \rangle \pm \vert S_R \rangle \} $. Here, getting a "plus" result in the laboratory means seeing the photon near a peak on the screen, and a "minus" result is seeing it in a trough.

You can check that measuring $\rho^{(S)}$ in the $\{ \vert \pm \rangle \}$ basis (or, in fact, any basis at all) gives equal probability of either outcome. This means no interference pattern, since photons are evenly spread over peaks and troughs. In particular, this is true no matter what happens to the idle photon; it could be carefully measured, or thrown away.

On the other hand, if you simply send the photon into a double slit experiment by sending it through a small hole and allowing the photon to enter either slit without being correlated with anything else, the evolution looks like

$\vert S \rangle \to \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \Big [ \vert S_L \rangle + \vert S_R \rangle \Big ] \quad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (2)$

which doesn't involve a second photon that "knows" anything. In this case, a measurement in the $\{ \vert \pm \rangle \}$ basis gives "plus" with certainty (or near certainty), meaning we see an interference pattern because all (or most) of the photons only land at the peaks.

Finally, suppose we place a second particle like a spin-up electron in front of the right slit such that the electron's spin flips if and only if the photons brushes by it on the way through the right slit. In this case we'd get

$\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \Big [ \vert S_L \rangle + \vert S_R \rangle \Big ] \otimes \vert e_\uparrow \rangle \to \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \Big [ \vert S_L \rangle \otimes \vert e_\uparrow \rangle + \vert S_R \rangle \otimes \vert e_\downarrow \rangle \Big ] \qquad \qquad (3)$

Now, although nothing has really happened to the signal photon as it passed through the right slit--it doesn't, say, get slowed down or deflected--the electron now knows where the photon is. In fact, this state is identical to the first one we considered except with the electron in place of the idle photon. If we make a measurement on the signal photon, we now get either outcome with equal likelihood, meaning the interference pattern is lost.

The process of the electron getting entangled with photon is known as decoherence. (Note that we only use that word when the electron is lost, like it usually is. If the electron was still accessible and could potentially be brought back to interact again with the photon, we'd just say they had become entangled.) Decoherence is the key process, and plays a fundamental role in understanding how "classicality" arises in a fundamentally quantum world.

Edit:

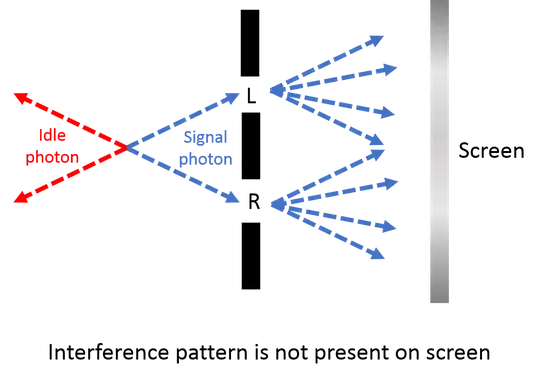

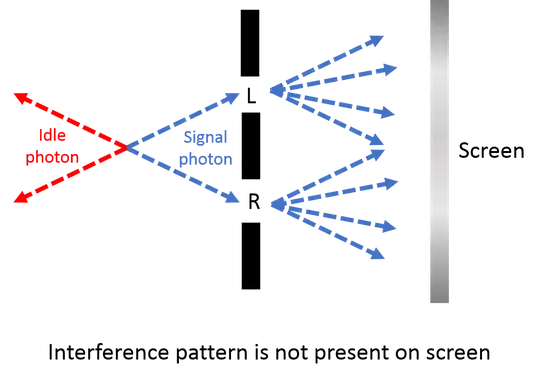

Make sure not to confuse two possible situations. The first is where the momenta of the idle and signal photon are correlated, and the slits are positioned to simply select for one of two possible outcomes, corresponding to equation (1) above:

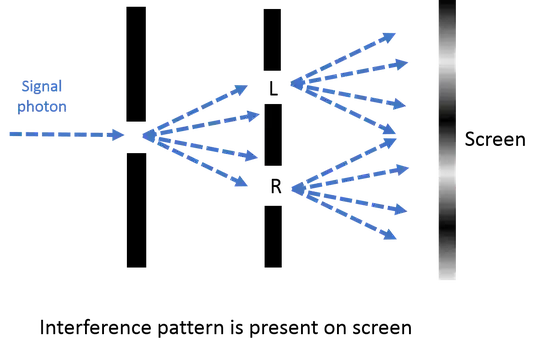

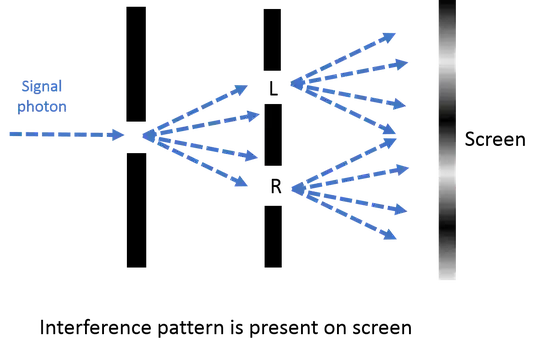

The second is where the signal photon's spread over $L$ and $R$ is not caused by an initial event correlating it with idle photon, but simply by its own coherent spreading when it is restricted to pass through a small hole, corresponding to equation (2):

Note here that there is no violations of conservations of momentum, a subtle (for beginners) consequences of the infinite dimensional aspect of the photon's Hilbert space. (The fact that the two-slit experiment is the canonical example for introducing quantum wierdness is unfortunate because of these complications.) When the photon is confined to a small initial slit, it necessarily has a wide transverse momentum spread.

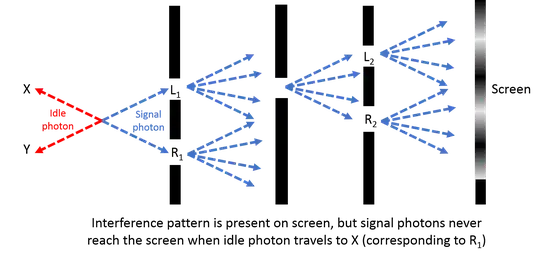

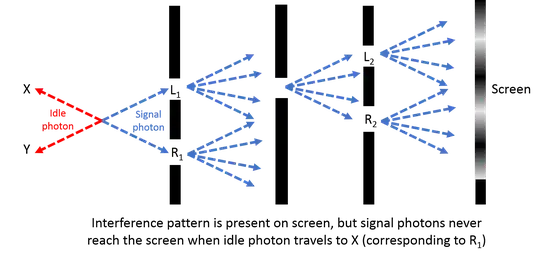

It might be helpful to concatenate these two cases:

Here, the idle photon is initially entangled with the signal photon, but the wall with the single slit destroys the signal photon for the $X/R_1$ outcome. When $Y/L_1$ happens, the signal photon can now be sent through 2 slits to produce and interference pattern. The idle photon's direction $X$ vs. $Y$ was correlated with the signal photon's $L_1$ vs. $R_1$, but it is never correlated with $L_2$ vs. $R_2$.