Let's say we have a cube of side length $a$ as a Gaussian surface in an electric field (in vacuum) and then we raise the strength of the electric field. As I understand, this rise in the field strength would travel through the field at the speed of light. This means that for a duration of $\frac{a}{c}$, the field strength, and thus the flux, would differ at the 2 opposing faces of the cube. This implies that the flux through the surface is non-zero and thus the charge inside it must also be non-zero by Gauss' Law. How is this possible?

3 Answers

As the field begins to rise at one place, it must also be doing related things at other places. To get an intuition about this, try sketching field lines on a piece of paper. The equation $\nabla \cdot {\bf E} = 0$ (for a charge-free region) implies that the lines, when drawn in 3-dimensional space, have to be continuous. The spacing between the lines indicates the field strength. If you have a field that is weaker at one place than at another, then when moving from the weaker to the stronger field region the field lines have to curve in a bit, to end up closer together where the field is stronger. When you count the lines going into and out of a given volume (this is what indicates the total flux through the surface) you find, at each instant of time, that as many lines go in as come out.

The overall conclusion is that the field at one place cannot grow larger without this kind of modification of the field at nearby places. Using the cube you described as a Gaussian surface, if the field is initially uniform then initially there is no flux in or out through the sides of the cube that are parallel to the field. But if the field subsequently becomes larger at one end of the cube than the other, then there must now be a flux across those sides.

For further clarity, for electric fields $\nabla \cdot {\bf E} = 0$ always holds in charge-free regions, and it follows that $$ \oint {\bf E} \cdot d{\bf S} = 0 $$ for charge-free regions, and this equation is correct and exact at all times, including for time-varying fields. The fact that changes at one place don't immediately propagate to places a finite distance away is all accounted for correctly. As those changes propagate, $\nabla \cdot {\bf E}$ remains equal to zero at each and every local region at each and every moment, and therefore its integral over a charge-free volume of any shape or size also remains zero.

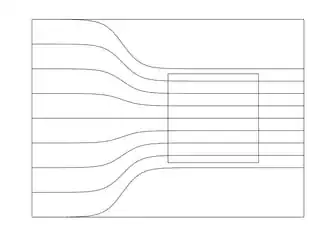

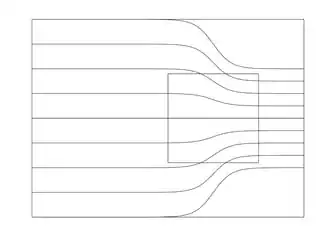

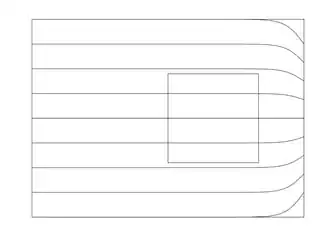

In the following three diagrams the rectangle is a Gaussian cylinder and the lines are electric field lines. The field has higher strength on the right than on the left. The diagrams show a change in the field propagating from left to right. The flux through any given edge of the rectangle is equal to the number of field lines crossing that edge.

- 65,285

The Maxwell equation that is said to embody Gauss's law for electric fields, namely $$\nabla.\mathbf E=\frac{\rho}{\epsilon_0}$$ holds at every instant. That's alright even if the field changes with time, because it is a local equation, applying at a point. However the same need not be the case for the integrated version (arguably Gauss's law itself): $$\int_S \mathbf E.d\mathbf S=\Sigma Q$$ in which $\Sigma Q$ is the total charge in the volume bounded by surface S. This volume is finite, and, as you say, changes in field strength at one boundary couldn't propagate instantaneously to other parts of the boundary. This integrated version is strictly for electrostatics. The Maxwell version is more general, applying at any point at any time, even if charges are moving and fields are changing.

- 37,325

Any disturbance in an electric field presumably propagates at the speed of light. Therefor a Gaussian surface some distance out, will lag in reflecting any changes in the enclosed charge.

- 12,280