In an earlier question, I asked about how to explain gravitational lensing to a layman in terms of propagating wave fronts, in a way analogous to the way an optical lens can be explained: the propagation velocity is inversely proportional to the refractive index of the glass and in the direction normal to the wavefront, which results in an initially plane wavefront being converted to a concave, converging wavefront.

Subsequently, I found several papers and presentations that described the vacuum as having an “effective refractive index” determined by the gravitational potential: (1), (2), (3), (4). The effective refractive index can then be used to explain gravitational lensing from either the ray perspective or the wave perspective.

This leads to a confusing inference, though, because dielectric constant is equal to the square of the refractive index (assuming that magnetic permeability is equal to 1). So, it seems that the vacuum around a gravitating mass must have an "effective dielectric constant" that varies with distance from the mass.

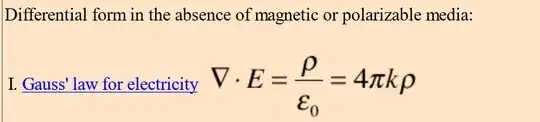

So far, so good. But Gauss' law

says that the effective charge of a charged particle depends on the dielectric constant of the vacuum surrounding it. If the dielectric constant is a function of distance $r$, then the effective charge is a function of distance.

This suggests, then, that radial dependence of the gravitational potential will cause the effective charge of a massive charged particle to vary with distance from the particle. (By the way, vacuum polarization [https://quantummechanics.ucsd.edu/ph130a/130_notes/node507.html] which is presumably an unrelated phenomenon, has a similar effect.)

However, answers and comments in response to this PhysicsSE question state emphatically that the divergence of E is zero in vacuum, regardless of the gravitational potential, according to the Einstein-Maxwell equations.

I suspect that the disconnect is due to the fact that derivation of the “effective refractive index” in (1), (2), (3), (4) assumes that space is flat. However, my confusion remains: it seems that a distant observer, ignorant of general relativity, would see a distance-dependent variation in the (effective) charge of a massive charged particle.

Is there a way out of this apparent contradiction?