Why if we specifically set Planck's constant equal to zero (the limit of it) do we sometimes get classical physics? I mean, what does it mean physically to set the constant equal to zero? Or to say it in another way, what did the first human to do this think of in order to come up with it?

I have seen in various situations somebody taking $h\rightarrow 0$, but what is making anybody who does this to take $h\rightarrow 0$ in the first place? Why would somebody take $h\rightarrow 0$ to take the classical limit in the first place?

- 8,020

3 Answers

What would somebody take h-->0 to take the classical limit in the first place?

Think for a minute about what the presence of Planck's constant in quantum theories does.

It creates a granularity to the amount of energy that can be stored in a mode (but not in general, to the amount of energy that can be stored in most systems).

Why does that matter?

Classically, a system in equilibrium disperses it's energy so that every available mode has (to a good approximation for macroscopic systems) an equal share of the energy. And it turns out that the value of that average is set entirely by the temperature of the system.

The classical problem is that an electromagnetic bath (as in cavity radiation) has an infinite number of modes, implying an infinite energy.

How does $h$ fix it?

Plank's ansatz was that each mode had a discrete energy-spectrum1 with granularity proportional to the frequency. This means that at high enough frequencies each mode could no longer have an energy close to the average, having to choose between zero and some value considerably larger than the classically assigned average. Add to that Boltzmann's rule for assigning the probability to occupation numbers and the mean energy of the (infinite number of) high frequency modes drops rapidly to zero, preventing the ultraviolet catastrophe.

So, why take $\lim_{h \to 0}$?

Classically there is no granularity, in Plank's approach there is, but it only matters when $hf \gtrapprox E$ for $E$ the classical average energy per mode. If you allow $h$ to get small, that condition is lost for a bunch of modes. Let $h$ go all the way to zero and it is lost for all modes. So you expect to recover the classical result in the limit of negligible $h$.

Is the procedure general?

Do note that it is not trivial to show that this limit gives the expected behavior in most cases. I am given to understand that the general problem is mostly solved, but only a few cases are accessible at a introductory level.

1 Watch out for the two meanings of "spectrum" here. In this case I'm talking about the allowed energies in a single frequency (or wavelength), not about a group of frequencies (or wavelengths)!

In classical physics there exists no h, and everything was going happily along until the data/measurements showed that classical electrodynamics + classical mechanics could not explain a number of data.

The datum that introduced the otherwise unknown and undefined h_bar was black body radiation. It was not possible to reconcile the fact that no excess ultraviolet radiation was observed from the experimental study of the radiation from bodies in the lab. Planck had the brilliant idea to assume that the electromagnetic radiation was not continuous but came in quanta of energy h*nu, where nu is the frequency, and could fit the data. Thus the constant took his name. It became obvious that a new framework for physical observations was emerging.

When the photoelectric effect, and then the spectra of atoms appeared in the labs the new framework became consistent by using this h*nu identification for photons that make up light. These data are not classical physics. Quantum mechanics was developed to explain it, and it soon became clear that all classical observations emerged from an underlying quantum mechanical framework, and this can be proven with advanced mathematical methods. For example, the way the classical electromagnetic radiation is built up by photons.

A second foundation stone for quantum mechanics is Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle. , HUP . This is what sets the stage for deciding whether quantum mechanical methods are needed or whether classical theories are adequate. For example

this inequality does not hold for classical physics, since h is a very small number. The constraints of the inequality appear at the level of particle physics, for micrometers and lower values. The statement that one gets classical physics when h is zero comes from the observation that classical momenta times classical dimensions multiplied have no lower bounds up to dimensions of micrometers and smaller . The handwaving statement "one gets classical physics if h is zero" is based on this relation.

The HUP is in the foundation of the mathematics of quantum mechanics, it appears in the commutator and anticommutator relations of operators representing measurable observables, like position and momentum. If h is zero, one has to fall back on the classical theories. , the consistency check also needs advanced mathematics to see the correspondence.

- 236,935

Why do we obtain Classical Physics by taking the limit of Planck's constant to zero?

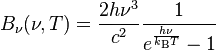

If you set $h = 0$ in Plank's law you will get $B_{v}(v,T)=2v^2k_BT/c^2 $ that is the Rayleigh–Jeans classical law which is valid up to one point and after that it comes in conflict with what was experimentally observed.

see: Planck's law

Now if you do not make $h = 0$ from the beginning and you want to solve the equation

Plank's law = Rayleigh–Jeans law, for small frequencies where both are valid

you get $h = 0$ for a perfect fit.

There is no other explanation for your question than pure math.

- 693