canada

The elements of sexual assault

To prove an offence, the Crown (prosecution) must establish both the actus reus and mens rea of the offence.

The actus reus of sexual assault is that:

- there is sexual touching;

- there is no consent to that specific sexual touching in the mind of the complainant.

"Complainant" simply means the "victim of the alleged offence" (Criminal Code, s. 2).

Criminal Code, s. 273.1:

Subject to subsection (2) and subsection 265(3), consent means, for the purposes of sections 271, 272 and 273, the voluntary agreement of the complainant to engage in the sexual activity in question.

Consent for the purpose of sexual assault is only the subjective consent by the complainant. "For the purposes of the actus reus 'consent' means that the complainant in her mind wanted the sexual touching to take place" (R. v. Ewanchuk, [1999] 1 SCR 330).

"The mens rea is the intention to touch, knowing of, or being reckless of or wilfully blind to, a lack of consent, either by words or actions, from the person being touched" (R. v. Ewanchuk, [1999] 1 S.C.R. 330).

Intoxication of the complainant

It is not the case that any degree of intoxication precludes consent. See R. v. G.F., 2021 SCC 20, para. 84. However, intoxication can reach the level that removes a person's capacity to consent. Capacity to consent is a precondition to consent: no capacity; no consent. Capacity is a question of fact and requires that the person "have an operating mind capable of understanding each element of the sexual activity in question" (R. v. G.F., 2021 SCC 20, para. 55). These are (para. 57):

the physical act;

that the act is sexual in nature;

the specific identity of the complainant’s partner or partners; and

that they have the choice to refuse to participate in the sexual activity.

The defence of honest but mistaken belief in communicated consent

Even where the complainant did not consent, there may be a defence available to the accused where they held an honest but mistaken belief that the complainant communicated consent. In order for this defence to be available, however, the accused must have taken reasonable steps to ascertain whether the complainant was consenting. Another Q&A answers what can and cannot constitute reasonable steps. In the context of an intoxicated complainant, the threshold for satisfying the reasonable steps requirement will be elevated, especially where the complainant may not even have the capacity to consent.

Intoxication of the accused

It is not a defence that the accused believed the complainant consented to the sexual activity where the accused's belief arose from the accused's self-induced intoxication (s. 273.2(a)(i)).

Canadian law recognizes that extreme intoxication can produce a state of automatism that precludes criminal liability. However, the state of intoxication required to produce a state of "automatism" is "a state of impaired consciousness, rather than unconsciousness, in which an individual, though capable of action, has no voluntary control over that action" (R. v. Brown, 2022 SCC 18, para. 2). Mere intoxication is not a defence to sexual assault (para. 4). There is much evidence that alcohol alone will not produce a state of automatism (para. 61).

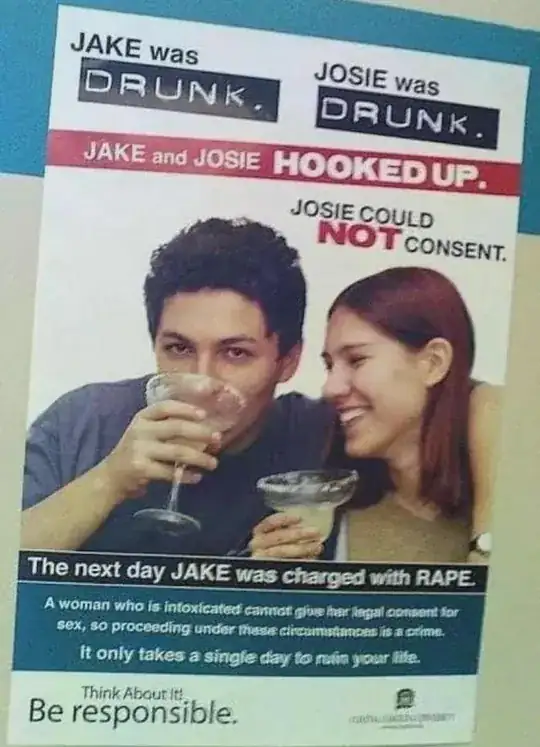

Application to the claims raised in the quesion

Canadian law does not support the proposition that only a male-gendered person would be charged with sexual assault in the circumstances described in the poster.

One or both of the people could lack the capacity to consent. The poster does not provide sufficient facts to determine whether this is the case for either Jake or Josie. However, it perhaps stipulates it when it says, "Josie could not consent." It is ambiguous whether it is stipulating this as a fact, or making a legal conclusion based solely on the fact that she was "drunk."

But, it is not true that "a women who is intoxicated cannot give her legal consent for sex" (see R. v. G.F., 2021 SCC 20, para. 84: "equating any degree of intoxication with incapacity would be wrong in law").

Further, we are also not told whether either of them in fact consented.

As to the defence of automatism, it is extremely unlikely, to the point that the Supreme Court of Canada doubts that it is even possible, that either of their levels of intoxication would result in automatism.

We do not have sufficient facts to know whether a defence of honest but mistaken belief in communicated consent would be available.

Charging decisions are discretionary. The guidelines depend on the province. But generally, to bring a charge, Crown counsel must believe there is a substantial likelihood of conviction (in B.C.) (or reasonable prospect of conviction in Ontario) and that the public interest requires a prosecution. Some provinces (e.g. B.C) have specialized charging guidelines for sexual assault. B.C's guideline provides that "it will generally be in the public interest to prosecute sexual assaults whenever the evidentiary test for charge assessment is met."