canada

It is a de facto power, not a right

In Hohfeldian terms, the jury's ability to nullify is a de facto power not a right (see Wesley Newcomb Hohfeld, "Some Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning" (1929) Yale L.J. 16, pp. 44–54).

The Supreme Court of Canada has recognized this distinction. While acknowledging that there can be a proper role for jury nullification, and that a jury has this de facto power, the Court rejected the proposition that this is a "right." See R. v. Latimer, 2001 SCC 1 (internal citations removed, emphasis from original):

58 This Court has referred to the jury’s power to nullify as “the citizen’s ultimate protection against oppressive laws and the oppressive enforcement of the law” and it has characterized the jury nullification power as a “safety valve” for exceptional cases. At the same time, however, Dickson C.J. warned that “recognizing this reality [that a jury may nullify] is a far cry from suggesting that counsel may encourage a jury to ignore a law they do not support or to tell a jury that it has a right to do so."

See also R. v. Morgentaler, [1998] 1 S.C.R. 30 (emphasis mine):

It is no doubt true that juries have a de facto power to disregard the law as stated to the jury by the judge. We cannot enter the jury room. The jury is never called upon to explain the reasons which lie behind a verdict. It may even be true that in some limited circumstances the private decision of a jury to refuse to apply the law will constitute, in the words of a Law Reform Commission of Canada working paper, "the citizen's ultimate protection against oppressive laws and the oppressive enforcement of the law". ...

...

The difference between accepting the reality of de facto discretion in applying the law and elevating such discretion to the level of a right was stated clearly by the United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit, in United States v. Dougherty, 473 F.2d 1113 (1972) ...

Likewise, the accused does not have a right to a jury that might nullify (Latimer):

68 The appellant’s second argument is a broad one, that the accused person has some right to jury nullification. How could there be any such “right”? As a matter of logic and principle, the law cannot encourage jury nullification. When it occurs, it may be appropriate to acknowledge that occurrence. But, to echo the words of Morgentaler (1988), saying that jury nullification may occur is distant from deliberately allowing the defence to argue it before a jury or letting a judge raise the possibility of nullification in his or her instructions to the jury.

69 The appellant concedes as much, but advances some right, on the part of the accused person, to a jury whose power to nullify is not undermined. He suggests the right to a fair trial under s. 7 of the Charter encompasses this entitlement. The appellant submits that there is a jury power to nullify, and it would be unconstitutional to undermine that power.

70 We reject that proposition. The appellant cannot legitimately rely on a broad right to jury nullification. In this case, the trial did not become unfair simply because the trial judge undermined the jury’s de facto power to nullify. ...

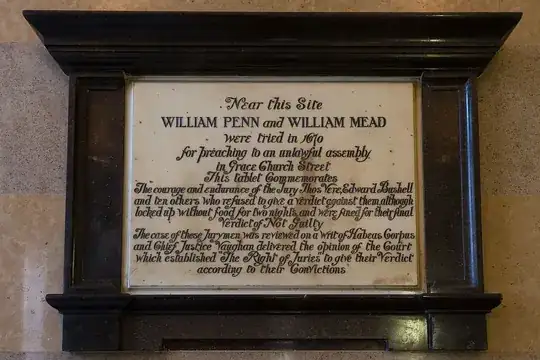

William Penn and William Mead plaque at the Old Bailey

William Penn and William Mead plaque at the Old Bailey