Could a lawyer be in trouble and lose his bar license for fighting for

a clearly unconstitutional position that under no reading could be

brought in line with the text of the constitution?

While it is possible, it isn't very likely, and has to be very extreme.

There are several different kinds of sanctionable conduct by a lawyer in court. The three main kinds, see, e.g. Colorado Revised Statutes, § 13-17-102, are:

Frivolous, i.e., not "warranted by existing law or by a nonfrivolous argument for extending, modifying, or reversing existing law or for establishing new law";

Groundless, i.e. an argument which, accepting the legal theory advanced as valid, is not supported by any evidence that could be admitted at trial; and

Vexatious, i.e. while not necessarily frivolous and groundless, conducted in bad faith and stubbornly litigious beyond what is reasonable and professional.

In practice, sanctions for "frivolous" litigation against professional lawyers are very rare due to the "nonfrivolous argument for extending, modifying, or reversing existing law or for establishing new law" clause.

The sort of legal arguments that result in sanctions for frivolous litigation are typically tax protester arguments that have been sanctioned literally thousands of times before, "sovereign citizen" type arguments that embrace an entire "bizarro world" worldview and not just novel legal arguments within a conventional legal worldview, and the sort of arguments that would only make sense if you are on psychedelic drugs or have schizophrenia (e.g., the sorts of legal arguments made in Alice in Wonderland).

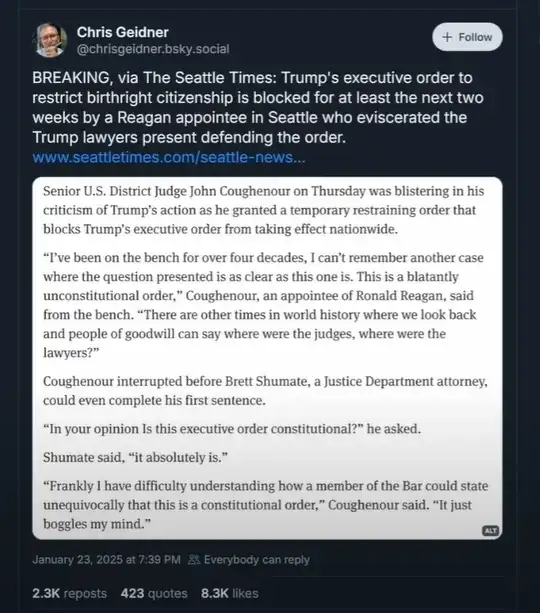

On the other hand, a lawyer can get into trouble for frivolous litigation, especially in ex parte legal proceedings, such as requests for temporary restraining orders or search warrants before an adversarial party is participating in the case, for failing to disclose that the position advanced by the lawyer is contrary to controlling law contrary to the position being advanced.

So, for example, a lawyer can argue, contrary to more than a century of precedents to the contrary that the 14th Amendment citizenship clause shouldn't apply to the children of illegal immigrants without being sanctioned. But if that argument is made in an ex parte proceeding, the lawyer doing so has a duty to flag the argument to the judge as one that is contrary to the controlling precedents and argue that despite those precedents that the law should be modified. Trying to sneak a deviation from the currently controlling existing law past the judge in the hope that the judge won't notice it, knowing that there is no one else before the court that can call the lawyer on this big ask, is an ethical violation by the lawyer doing so and is sanctionable.

Far more common are sanctions for "groundless" and "vexatious" litigation.

For example, this was the basis of most of the many sanctions entered against Trump supporting lawyers in the 2020 election litigation.

While attorneys can accept what their clients tell them to some extent, they have a legal duty to do some reasonable due diligence to confirm that the factual allegations made by their clients have some basis in reality.

The 2020 Trump election fraud claim lawyers, for example, were sanctioned mostly (1) for bringing lawsuits that had no factual basis, rather than because the legal theories advanced were improper if the facts alleged had been true, or (2) for vexatious litigation in the form of an unwillingness to abide by a judge's rulings and continuously raising the same points over and over again, beyond what was necessary to preserve their rights on appeal.

Part of the confusion arises from the fact that the world "frivolous" while sometimes used in the strict sense used above, is sometimes used in a less strict sense to refer to any of the three kinds of sanctionable litigation conduct.

With respect to some of those arguments:

"Congress has the power to ban any free speech" (contra 1st

Amendment),

In that form, the argument might be frivolous. But it certainly isn't frivolous to argue that certain particular kinds of speech are not protected (which is true of many kinds of speech today like fraudulent commercial speech or true threats or time, place, and manner restrictions on speech). One might also argue, less frivolously, that this ought to be a non-justiciable political question since it contains so many judgment calls, and that it should be up to Congress to define what constitutes free speech.

"There is no such right to own any firearms or weapons" (contra 2nd

Amendment)

This was the accepted reading of the Second Amendment under the relevant U.S. Supreme Court cases prior to Heller in 2008 (i.e. for more than two centuries). The argument that the Second Amendment applied to state law, and not just federal law, came a few years after that. The Second Amendment was read previously as a federalism provisions that allowed state governments to have militias and armed police forces. So, while this reading is contrary to currently controlling federal law, it isn't frivolous. The "well-regulated militia" language of the Second Amendment also implies that firearm or weapon ownership can be regulated in some manner, making it something less than a true absolute right.

"The president is elected for life" (contra 22nd Amendment & Art. II,

S1.C1.)?

In that bare form, this would be frivolous. But, with a subtly different argument that was a little less brazen, for example, stating that the President may remain in office indefinitely past the end of the term to which the President was elected, until Congress mandates that an election be held, or if legal struggles cast into doubt the ability of states to conduct a valid election, it might not be frivolous.