As mentioned by others, in Linux an interpreter directive method is used (storing some metadata in a file as a header or magic number so the correct interpreter can be told to read it) rather than the filename extension association method used by Windows.

This means you can create a file with almost any name you like... with a few exceptions

However

I would like to add a word of caution.

If you have some files on your system from a system that uses filename association, the files may not have those magic numbers or headers. Filename extensions are used to identify these files by applications that are able to read them, and you may experience some unexpected effects if you rename such files. For example:

If you rename a file My Novel.doc to My-Novel, Libreoffice will still be able to open it, but it will open as 'Untitled' and you will have to name it again in order to save it (Libreoffice adds an extension by default, so you would then have two files My-Novel and My-Novel.odt, which could be annoying)

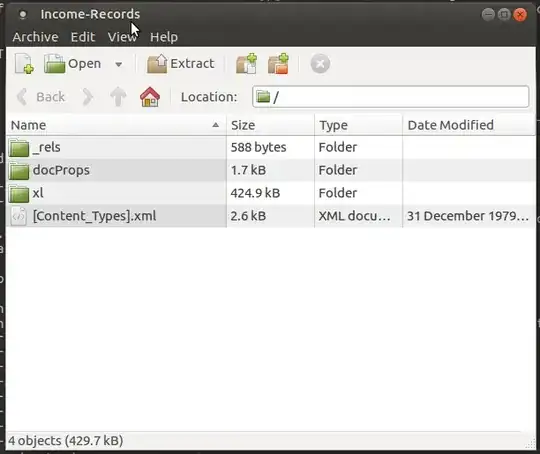

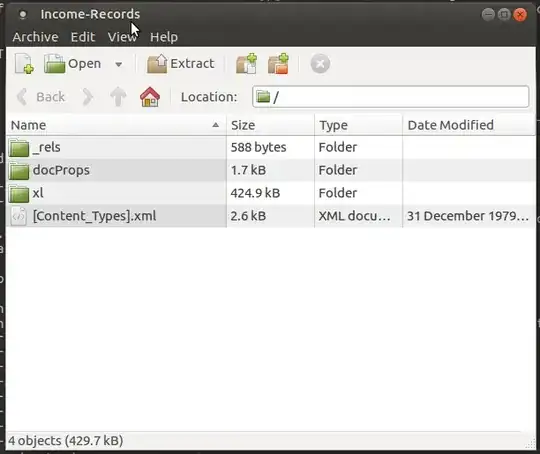

More seriously, if you rename a file My Spreadsheet.xlsx to My-Spreadsheet, then try to open it with xdg-open My-Spreadsheet you will get this (because it's actually a compressed file):

And if you rename a file My Spreadsheet.xls to My-Spreadsheet, when you xdg-open My-Spreadsheet you get an error saying

error opening location: No application is registered as handling this file

(Although in both these cases it works OK if you do soffice My-Spreadsheet)

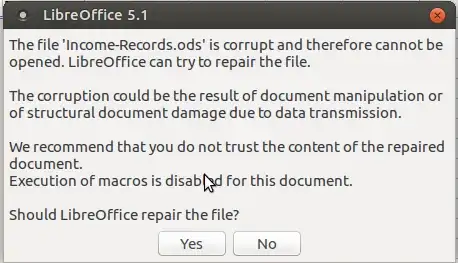

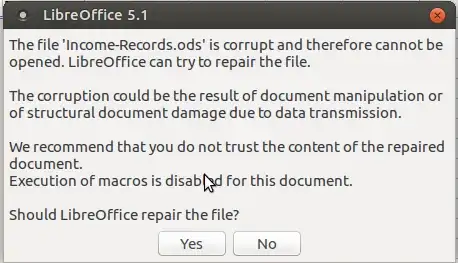

If you then rename the extensionless file to My-Spreadsheet.ods with mv and try to open it you will get this:

(repair fails)

And you will have to put the original extension back on to open the file correctly (you can then convert the format if you wish)

TL;DR:

If you have non-native files with name extensions, don't remove the extensions assuming everything will be OK!