I think every writer is welcome to be different.

The problem with forming "rich mental pictures" is that heavily detailed physical description bores [most] readers rather quickly; it overwhelms their memory for the details.

What sticks with [most] readers is emotional states. Surprise, awe, intimidation, hope, despair, depending upon what the scene is supposed to convey.

Read the professionals, the best selling authors, and see how many details they include in describing scenes. They guide the reader's imagination, but do not dictate every detail. They provide a few details to prompt us, but then rely on us to fill in the details from our own experience.

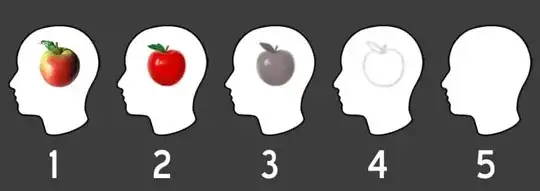

Visualization is important, but I'd encourage you to let go of the notion that readers have to visualize exactly what you visualize, because, as they say, an image is worth a thousand words.

Or to paraphrase, to describe an image accurately requires a thousand words.

And those thousand words will probably bore the reader so much they will stop reading.

Visualize, but then isolate from your rich image the most important few details of the image that determine the emotional state of the character.

Let me invent a scene to illustrate:

Lilith woke squinting in pain,she put a hand to her forehead and recoiled from the touch, her fingers bloodied.

She sat up. The glen was strewn with bodies. Marcus, beside her, his throat laid open. She rose. Harold, clouded eyes staring at nothing. He was gone. All gone. At the edge, she spotted a purple kerchief -- Fen! She sprinted to him, and fell to her knees.

Fen. Fen was dead. She fell on him, cradled him, she cried. She sobbed. Fen was dead.

Too much detail will bore the reader. Your job as a writer is not to reproduce precisely what you see in your imagination, but to help the reader visualize an approximation of it, without boring them with precision.

It is an important balance to strike: Too much precision and the story drags and feels boring. Too little information and the story becomes confusing.

It isn't important, in the Lilith scene above, precisely what the "glen" looks like, or what Marcus, or Harold look like, or the positions of their bodies. And all that matters about Fen is he wears a purple kerchief, for us to let the audience know she recognizes him from afar, and we can tell from her reaction that she loved Fen, his death hits her the hardest.

There is a movie unfolding in the reader's imagination. You can imagine with all the detail you like, and that is good. But you cannot convey all of it without slowing down that movie in the reader's head.

How much detail you can include depends on the pace of movie, in the moment. In a battle scene, you cannot provide a lot of information without slowing this battle to a crawl, which would kill the excitement of the battle.

You can provide greater detail in the naturally slower moments, like recovering and patching up after the battle. Or marching two days to the next battle.

Keep in mind the pace of the story, the movie in the reader's head. Much of the art of writing is figuring out how much to tell, and how much you can leave unsaid without losing the reader. It is how to isolate the handful of important anchoring details in the scene that ensure the reader is seeing approximately the same scene as you see, even if yours contains much more detail.