It doesn't seem to be NP-complete. But has it been proved to be NP-hard?

5 Answers

If you mean that you seek the order $r$ of $a$ modulo $N$, where $N$ is an integer and $a \in \mathbb Z_N^*$, then note that this problem can be efficiently reduced classically to the integer factoring problem (IFP), and vice versa (probabilistically). The best known classical algorithm for the IFP has sub-exponential time complexity, and to e.g. quote Cohn the IFP is "almost undoubtedly not NP-hard".

Some clarifications in response to John's comment: To reduce the order-finding problem (OFP) to the IFP, first factor $N$ completely, then compute the Carmichael function $\lambda(N)$ given the factorization, then factor $\lambda(N)$ completely, then use that $r$ must divide $\lambda(N)$ to quickly find $r$. (Essentially start by setting $r$ to $\lambda(N)$ and then divide off as many factors as can be removed without voiding the requirement that $a^r \equiv 1 \:\: (\text{mod } N)$. Optimizations are possible when factoring $\lambda(N)$: Since we know the complete factorization of $N$, we need only factor $p_i - 1$ for $p_i$ the distinct prime divisors of $N$.) To reduce the IFP to the OFP probabilistically, proceed as Shor describes in [Shor94] [Shor97], or as I describe in my work [E21b], or similar.

The implication is that the OFP in $\mathbb Z_N^*$ is not harder than the IFP. In practice, as far as I know, the best option asymptotically would be to use the aforementioned reduction, and the GNFS. Hence the answers to the two questions are (i) (at most) sub-exponential and (ii) no there is no such proof, as far as I know. (Also, since the OFP is efficiently tractable quantumly, the implication of the OFP being NP-hard would be that we could solve any problem in NP efficiently quantumly. This appears unlikely.)

Some clarifications in response to Steve's comment: We have that $r \le \lambda(N) < N$. It follows that there are at most $\log_2(\lambda(N)) < \log_2(N) = n$ prime factors in the complete factorization of $\lambda(N)$ to consider when accounting for multiplicity (as each factor must be at least two). We measure the complexity in the bit length $n$ of $N$, so in other words there are at most linearly many factors to consider. Dividing them off one by one as described above is hence efficient.

With respect to Steve's second comment: Note that we first let $r$ be equal to $\lambda(N)$ and then simply divide off the factors that can be removed one by one. More specifically, if $\lambda(N) = q_1 \cdot \ldots \cdot q_m$ for $q_1, \, \ldots, \, q_m$ primes (that may occur with multiplicity), first let $r \leftarrow \lambda(N)$ and then for each $q_i$: If $a^{r/q_i} \equiv 1 \:\: (\text{mod } N)$, let $r \leftarrow r / q_i$. At the end of this process, $r$ will be the least positive integer such that $a^r \equiv 1 \:\: (\text{mod } N)$, as desired. (Again, optimizations are possible. I use $\leftarrow$ to denote assignment.)

A side note not directly related to the question: The hard part in the reduction from the OFP to the IFP is computing the aforementioned complete factorizations. These factorizations do not depend on $a$, but rather only on $N$. Hence, if the orders of many different elements are to be computed in the same group $\mathbb Z_N^*$, it suffices to pre-compute the factorizations once. This is somewhat interesting, in that a quantum computer could be used to perform the pre-computations, so as to enable a classical computer to then act as an order-finding oracle.

(Note that the aforementioned reduction from the OFP to the IFP is not new in any sense. For one earlier mention of such a reduction, see e.g. Long's unpublished note.)

- 1,444

- 7

- 26

Here's my answer, for the record.

First, when we're talking about problems being $\text{NP}$-hard or $\text{NP}$-complete, we're talking about decision problems — so we need to express order finding as a decision problem. A traditional way to do this is to identify the yes-instances of the problem with strings in a language such as this. $$ \mathrm{ORDFIND} = \bigl\{ (a,N,k) \,:\, \exists\; r\in \{1,\ldots,k\}\;\text{such that}\;a^r \equiv 1\; (\mathrm{mod}\; N) \bigr\} $$ To be clear, $(a,N,k)$ refers to three positive integers, $a,$ $N,$ and $k,$ encoded as strings using binary notation. Notice that, if we were granted a way to solve this decision problem, we could use it to compute the order of $a$ modulo $N$ efficiently using binary search over the range $k\in\{1,\ldots, N-1\},$ for instance. So, this is a reasonable way to do this; we haven't made the problem artificially easy by turning it into a decision problem.

For this answer, a key thing we'll observe about the classical complexity of this problem is that $\mathrm{ORDFIND} \in \text{NP}\cap\text{co-NP}.$ Another way to say this is that, for any input $(a,N,k),$ there's a polynomial-length certificate that can be checked, in polynomial time, to certify whichever of the two inclusions $(a,N,k)\in\text{ORDFIND}$ or $(a,N,k)\notin\text{ORDFIND}$ is the one that is true.

From basic complexity theory we know that, if any language in $\text{co-NP}$ is $\text{NP}$-hard, then $\text{NP} = \text{co-NP}.$ We don't know how to rule out this possibility, which is par for the course in complexity theory, but it would be pretty shocking if this were true. Regardless of how likely or unlikely the equality $\text{NP} = \text{co-NP}$ might be, a proof one way or the other would certainly represent a monumental advance in complexity theory. So, if we're restricting our attention to humans living on this planet, then no — it doesn't appear that anyone has proved that order finding is NP-hard. We probably would have have heard about it if they had.

Now let's argue that $\mathrm{ORDFIND} \in \text{NP}\cap\text{co-NP}.$ Formally speaking, this means proving the two inclusions $\mathrm{ORDFIND} \in \text{NP}$ and $\mathrm{ORDFIND} \in \text{co-NP},$ which might ordinarily be done separately. In this case, however, the same argument works for both.

We need just a bit of number theory before going further. First, if $\gcd(a,N)>1,$ then there is no positive integer $r$ such that $a^r \equiv 1\; (\mathrm{mod}\; N),$ so $(a,N,k)\notin\text{ORDFIND}$ in this case, irrespective of $k.$ The first step of the certificate checking procedure is therefore to compute $\gcd(a,N),$ and to reach this conclusion if it so happens that $\gcd(a,N)>1.$

It remains to consider the case that $\gcd(a,N)=1,$ which is the interesting case in which the order actually exists. For the sake of completeness, the order of $a$ modulo $N$ is the smallest positive integer $r$ for which $a^r \equiv 1\; (\mathrm{mod}\; N).$ The argument that follows uses (perhaps implicitly) that a positive integer $s$ satisfies $a^s \equiv 1\; (\mathrm{mod}\; N)$ if and only if $r$ divides $s.$

And now, for a given input $(a,N,k),$ for which we're assuming $\gcd(a,N) = 1,$ the certificate will be a string of bits encoding the following:

- A prime factorization $r = p_1^{b_1}\cdots p_m^{b_m}$ of the order of $a$ modulo $N.$

- Certificates of primality for $p_1,\ldots,p_m.$

We'll argue that we can check the validity of such a certificate deterministically in polynomial time.

First let's talk about the certificates for primality. We could do away with these and use the AKS (Agrawal, Kayal, and Saxena) primality test, which runs in deterministic polynomial time. That's a complicated algorithm, though. Those wishing to be fully convinced that there's an actual theorem here might instead opt to learn about Pratt certificates for primality, which are based on simple number theory. The point of checking the primality of $p_1,\ldots,p_m$ is to be sure that $r = p_1^{b_1}\cdots p_m^{b_m}$ is a valid prime factorization, so hereafter we'll assume that this is indeed so. If it is not, the certificate is rejected.

Now we need to check that $r$ is actually the order of $a$ modulo $N.$ We can do this as follows:

Compute $a^r\;(\mathrm{mod}\; N).$ This can be done efficiently using the power algorithm, also known as repeated squaring. If $a^r \not\equiv 1\;(\mathrm{mod}\;N)$ then $r$ is not the order of $a,$ so the certificate is rejected in this case. Otherwise, if $a^r \equiv 1\;(\mathrm{mod}\;N),$ we continue to the next step, knowing that the actual order must divide $r.$

We now check that the order is not a proper divisor of $r.$ This can be done by checking, for each prime $p\in\{p_1,\ldots,p_m\},$ that $a^{r/p} \not\equiv 1\; (\mathrm{mod}\; N).$ Again, the required computations can be performed efficiently with the help of the power algorithm. If any of the checks fail, the certificate is rejected.

The idea behind the second step is that every proper divisor of $r$ must be divisor of $r/p$ for at least one prime $p$ dividing $r.$ It follows that if the order of $a$ is a proper divisor of $r,$ then we'll necessarily get $a^{r/p} \equiv 1\; (\mathrm{mod}\; N)$ for at least one of the primes $p\in\{p_1,\ldots,p_m\}.$ This is where the primality of $p_1,\ldots,p_m$ comes into play; if it turned out that one or more of these numbers actually wasn't prime, the checks wouldn't be sufficient to conclude that the order is not a proper divisor of $r.$

Finally, once it has been verified that $r$ is the order of $a$ modulo $N,$ we can easily verify that a given input $(a,N,k)$ is in $\text{ORDFIND},$ or that it is not in $\text{ORDFIND},$ by comparing $r$ with $k.$

So, although we phrased the problem as a decision problem to get the complexity part right, the method described here is more naturally viewed as a way to certify the order. In a nutshell, having a prime factorization of the order makes that easy.

- 6,342

- 18

- 28

[0001] If order-finding were NP-hard, then we would conclude that the polynomial hierarchy would collapse, and also separately that a quantum computer could efficiently solve any NP-complete problem. We do not believe that either conclusion is true, therefore we believe that order-finding is not NP-hard.

[0002] Alternatively, if we could prove that order-finding is not NP-hard, then we would show that P$\ne$NP. We believe that proving this is very very difficult.

[0002] Even (in my opinion unlikely) if we do prove that order finding is in P, this would be of only limited value in deciding whether or not P$\ne$NP.

[0003] Therefore, we don't believe we can find an easy proof that order-finding is not NP-hard (although we all believe that order-finding is not NP-hard).

[0004] Briefly, a problem that is both in a class and also hard for that class is the defining property of being complete for that class. Thus, if we show that a problem, known to be in NP, is also NP-hard, then we would conclude that the problem is NP-complete.

[0005] Additionally, if we can show that the problem is both in NP and also in co-NP, then under the assumption that the problem is also NP-hard, the problem would be NP-complete, but also NP$\subseteq$co-NP. We could take any problem in NP and reduce that problem to our given problem and find the co-NP certificate. However, this is not likely to be true as it will lead to a collapse of the polynomial hierarchy; most people think that the polynomial hierarchy is infinite.

[0006] Still further, if we can show that the problem is both NP-complete and also in BQP, we could conclude that NP$\subseteq$BQP. For example, we could take any problem in NP, reduce it in polynomial time to our particular problem that is in BQP (with a large but still polynomial number of bits), and feed the as-reduced problem into to our quantum computer to solve efficiently solve our instance, and from there find the solution to our original NP problem. However, this is also not likely to be true as many people believe that quantum computers cannot efficiently solve NP-complete problems.

[0007] But, in order to show that a problem, that is in NP is also not NP-complete or NP-hard, we would end up showing that P$\ne$NP, which is known to be a very hard problem. If the problem is also in BQP, then we would show that NP$\ne$BQP, which is also known to be a very hard problem (although not worth the \$1M Clay prize).

[0008] Taking the order-finding problem, given an integer $N$ written with $n=\lceil\log_2 N\rceil$ bits along with another integer $a\in\mathbb Z^*_N$, broadly I think we can define the order-finding problem as that of finding the least positive integer $r$ such that $a^r\pmod N\equiv 1$.

[0009] As is usual we can convert this to a decision problem, by giving the tuple $(a,N,r')$ and asking for an $r\le r'$ such that $a^r\pmod N\equiv 1$. When framed this way, I guess it's clear that this $r$ itself is a polynomial-size witness - we can trivially check whether $r\le r'$, and we can, e.g., use modular exponentiation by repeated squaring to check whether $a^r\pmod N\equiv 1$.

[0010] In order to find the actually smallest such $r$, we can do a standard binary search on $r'$. For example, if we show that $r\le r'$ and also that $a^r\pmod N\equiv 1$, then we can certify that another $r''\le r'/2$ exists such that $a^{r''}\pmod N\equiv 1$. Binary searching at best adds a $\log n=\log\log N$ factor to the size of the certificate.

[0011] Additionally, it can be shown that order-finding is in co-NP, meaning that there is a polynomial-size certificate to show that there is no $r\le r'$ such that $a^r\pmod N\equiv 1$. This can be done by appealing to primality testing, with, say, the AKS theorem.

[0012] Actually, it is not required to efficiently find a certificate of primality or of co-NP'ness, which is what AKS gives you; rather, it suffices to efficiently verify co-NP'ness. Thanks to a comment from @John and from Kuperberg and Eppstein on a MathOverflow thread I also learned about Pratt certificates.

[0013] Taking the above two together, we would conclude that, if order-finding were NP-complete, then NP$\subseteq$co-NP, and the polynomial hierarchy would collapse. Thus, we can conclude under the hypothesis that the polynomial hierarchy is infinite, order-finding is not NP-hard.

[0014] Still further, we know from Shor that order-finding is in BQP. Thus, we can conclude under the hypothesis that NP$\not\subseteq$BQP, that order-finding is not NP-hard.

[0015] Additionally if we believe that order-finding is not in P, then it will likely be very difficult to prove that order-finding is or is not NP-complete. For example, if we prove that order-finding is not NP-complete, then under the assumption that order-finding is not in P we can conclude that order-finding is necessarily an intermediate problem, between P and NP-complete. Under Ladner's theorem, proving order-finding is not NP-complete and also not in P leads us to conclude that P$\ne$NP; thus if we were able to prove that order-finding is not NP-complete then we would prove that P$\ne$NP, which is why we don't beleive it's easy to prove that order-finding is not NP-complete.

[0016] All things considered, order-finding is likely not NP-hard, because if it were, then many implications that we do not believe to be true would then be true. However, showing that order-finding is not NP-hard is likely to be very difficult, at least because doing so might serve to split P from NP, or BQP from NP, which are believed to be very hard problems.

[0017] If order-finding were proven to be NP-hard, then the polynomial-time hierarchy would collapse but we may or may not still be in a world where P$\ne$NP, so it could still "hard" to find solutions to 3-SAT with our conventional classical computers. But we should be very happy because NP$\subseteq$BQP and we'd redouble our efforts for fault-tolerant quantum computers!

- 15,378

- 3

- 26

- 83

Martin and Mark have posted an elaborate and convincing argument. Since I joined Watrous's expedition a bit late, I will mostly try to complement their post by

putting the order-finding and Factorization problem into a broader perspective.

and why SAT, an NP-hard problem, is unlikely to reduce to (decision version of) order-finding irrespective of the type of reduction we use.

[Main addition]

I will start with a bird's-eye view of the complexity theory landscape where FACTORING and related number theory problems reside. Then, under certain widely held conjecture like-

- Conjecture 1: $NP\not\subset BQP$ and

- Conjecture 2: Polynomial Hierarchy ($PH$) doesn't collapse (at any level)

one can develop an intuition why it is very unlikely that SAT problem reduces to Order-finding either by using (1) deterministic, (2) probabilistic or even (3) quantum reduction.

[Web of reduction]

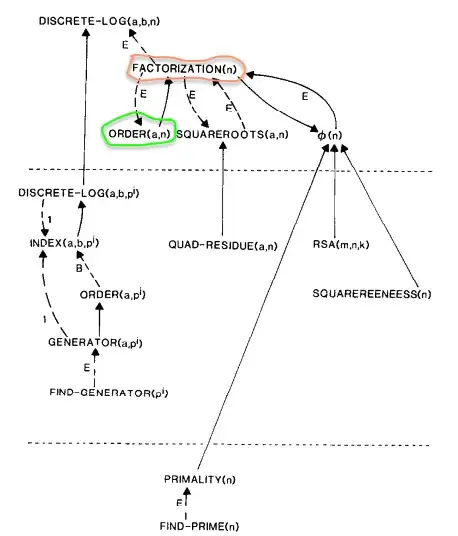

The diagram below has been taken from Heather Woll (1987)

It surveys number-theory problems and how one problem can be converted (or reduced) to another problem. We can see how the Factoring and order-finding problem reduces to each other (in the red and the green circles, respectively). Martin has elaborated on this quite nicely in his post. To quote the paper,

the solid line pointing from order-finding to Factoring means the reduction is deterministic.

the broken/dashed line pointing (with symbol 'E') from Factoring to order-finding means the reduction is probabilistic.

[Limitation of all three reduction techniques]

In some problem settings, it is conjectured that randomized reduction is more powerful than deterministic reduction. Similar consensus is about quantum reduction over randomized reduction. But we can prove that none of the reduction technique is likely to reduce SAT to ORDER(a,n).

Using the theorem that (decision version of) order-finding is in $BQP$, we see the following consequences-

Assumption 1: SAT deterministically reduces to ORDER(a,n).

Consequence 1: SAT$\in P^{BQP} =BQP$. [Thus, Assumption 1 violates the conjecture $NP\not\subset BQP$]

[Note: $P^{BQP}\subseteq BPP^{BQP} \subseteq BQP^{BQP} = BQP$, self low property of BQP]

Assumption 2: SAT randomly reduces to ORDER(a,n).

Consequence 2: SAT$\in BPP^{BQP} =BQP$. [Thus, Assumption 2 also violates the conjecture $NP\not\subset BQP$]

Assumption 3: SAT quantumly reduces to ORDER(a,n).

Consequence 3: SAT$\in BQP^{BQP} =BQP$. [Thus, Assumption 3 violates the conjecture $NP\not\subset BQP$ too.]

[Another evidence against NP hardness]

As mentioned in Mark's post, FACTORIZATION $\in$ NP$\cap $co-NP.

Thus, the reduction of SAT to FACTORIZATION would violate $PH$ doesn't collapse conjecture. It requires a separate discussion why this conjecture is likely to be true. Interestingly, there is no need of BQP to argue why $PH$ is fully robust. It is totally a classical complexity theory result.

[Prognosis]

It appears there is more evidence to expect ORDER(a,n) and FACTORIZATION(n) is not NP-hard than the opposite.

[Yet another reason: Abelian vs non-abelian HSP perspective]

(Take it as informal remark)

ORDER(a,n), FACTORIZATION(n), DISCRETE-LOG(a,b,n) are unified by HSP over finite Abelian group. Character of such groups has some "nice" property which clever/Shor BQP algorithm tends to exploit.

But there are some problem that is known to be an instance of non-abelian HSP like Graph isomorphism (an NP problem) and (a version of) of shortest vector problem (an NP-hard problem). They don't have the same "nice" property. Thus, the toolkit used for abelian case is not sufficient to design a BQP algorithm for GI and the variant of SVP.

This could be perceived as a way to understand why $NP$ is easily able to resist being a subset of $BQP$. Thus giving one more reason to suspect the conjecture $NP\not\subset BQP$ might be true. And, we have seen this conjecture is sufficient to deduce ORDER(a, n) is not NP-hard.

- 883

- 1

- 6

- 20

I think it's not well defined at any of the given groups. Currently, I'd say it lies in BQP (Bounded-Error Quantum Problem) group due to Shor's algorithm.

- 15

- 7