I'm asking this question here because the doubt comes from trying to understand a physical problem (kinematics of rotations), but this question would easily fit the MathExchange site also.

I was reading Chapter 4 - The Kinematics of Rigid Body Motion from the book Mechanics (3rd Edition) by Goldestein; more specifically pg. 152. I was trying to understand the notation of rotations and different representation in various frame of reference, whose notation I find very confusing.

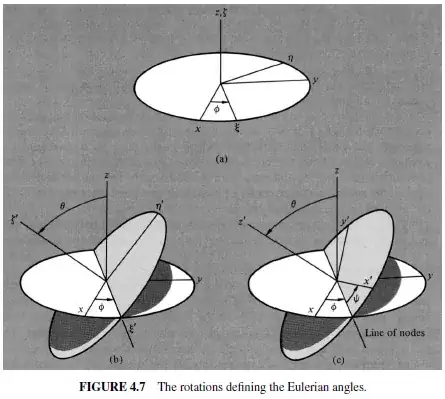

Goldestein starts explaining that we need three independent rotations to completly rotate an object.

First we rotate the $xyz$ axis to $\xi \eta\zeta$. Then from $\xi \eta\zeta$ to $\xi '\eta'\zeta '$ and finally from $\xi \eta\zeta$ to $x'y'z'$.

The first rotation about $z$ can be expressed as: $$ \boldsymbol \xi = D \mathbf x $$

The second rotation: $$ \boldsymbol \xi ' = C \boldsymbol \xi $$

And the last rotation: $$ \mathbf x ' = B \boldsymbol \xi ' $$ Hence, the matrix of the complete transformation is: $$ \mathbf x' = A \mathbf x $$ where $$ A = B C D $$ Until now everything make sense.

Then, the inverse transformation from body coordinates to space axes follows as: $$ \mathbf x = A^{-1} \mathbf x' $$

This stops to make sense to me. As from what I understand, I interpret a rotation as a set of displacements of points by an angle that conserve lengths. This points were initially on world space and after the rotation they are still on world space. Why would a change of basis would be needed?

I would interpret the equation $\mathbf x' = A \mathbf x$ as: "I know where the point $\mathbf x$ was before the rotation. Then I apply rotation $A$, to get where $\mathbf x$ is now after the rotation (given by $\mathbf x'$)". Why after applying a rotation now we are "seeing" things from the body point of view?

The matrix $A$ is completely expressed in body coodinates as this answer suggests. But why?

And also, Goldestein states that, for example, the matrix $D$, which he writes as: $$ D = \begin{pmatrix} \cos \phi & \sin \phi & 0 \\ -\sin \phi & \cos \phi & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} $$ is a counter clockwise rotation, but clearly: $$ \begin{pmatrix} \cos \phi & \sin \phi & 0 \\ -\sin \phi & \cos \phi & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \cos \phi \\ -\sin \phi \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} $$ the cartesian basis is being rotated clockwise. As this post and this post might hint, this must be a problem of basis representation of the linear maps but the notation is confusing me.

I would be pleased if someone could reconcile both points of view, clarify how to know when we are expressing things from the body axis or from the global axis, and when the changes of basis is needed.

EDIT: I also found this answer, which also adds another interpretation to rotations. This question explanation agrees with what I said about how I interpret rotations. So now there is one more interpretation... Which one is correct, or how could we reconcile both views?