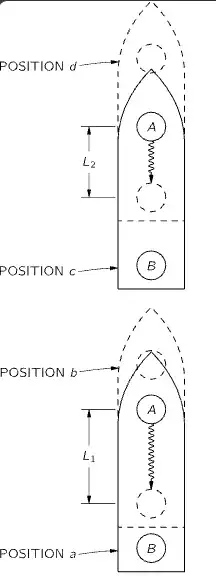

In section 42-6 of The Feynman Lectures on Physics (The speed of clocks in a gravitational field), Feynman describes a thought experiment involving two clocks placed at different positions inside an accelerating rocket. He concludes from an external reference frame that the light traveling from the top clock to the bottom clock covers shorter and shorter distances as the rocket continues to accelerate, indicating that the lower clock (clock B) runs slower.

My confusion is as follows: This conclusion is drawn from an external, inertial observer's perspective outside the rocket. However, from the viewpoint of someone inside the rocket (a non-inertial, accelerating reference frame), the distance between the two clocks remains constant. How can Feynman use observations made from an external inertial frame to infer that the lower clock inside the rocket truly runs slower? Doesn't the observer inside the rocket always measure the same distance and, presumably, the same speed of light?

In other words, how does observing shorter travel distances for the light from an external frame justify concluding time dilation inside the accelerating rocket, when the internal observer sees no change in distance or speed of light?