Disclaimers

- It is not possible to give a quantitative explanation of the relationship between incident electromagnetic energy and the digital ADU readings of a camera pixel without a discussion of the quantization of the energy in the electromagnetic field.

- My semi-conductor physics is a bit poor so that part of the answer may be lacking. Perhaps other answers or comments can help clarify anything I get wrong or explain poorly.

Photodetectors

I'm going to talk about charge coupled device (CCD) sensors.

A single pixel on a CCD sensor includes a semiconducting device which produces charges when it is driven by electric fields from electromagnetic radiation. The device includes a photodetection region and an electron storage region. My vague understanding is that the photodetection region is a depletion region of some semiconducting interface. When electromagnetic fields impinge upon this region, the oscillating electric fields excite an electron/hole pair from their bound valence bands into their respective conducting bands. This photodetection region is in a DC bias field produced by a gate electrode. When the electron/hold pairs occupy the mobile conduction bands, and in the presence of the gating electric field, the electrons are swept into a different region of the device used for charge storage. This region is essentially a capacitor which is used to store charge. The electrons which are excited and stored in this process are often called photoelectrons.

Note that there are two electric fields. One is the electric field of the incident electromagnetic radiation. This is what is being detected. The second is the static electric field internal to the semiconducting device due to the gating. These two electric fields should not be confused. Note that this already answers a part of the question: It is the oscillating electric field from the incident electromagnetic radiation that is being detected by a camera sensor. The incident oscillating magnetic field is unrelated.

Quantitative Photodetection - How Many Photoelectrons are There?

We now know that the electric field from the incident electromagnetic field excites electrons into the conduction band of the semiconductor and that this is the first step in photodetection. But what is the quantitative relationship between the incident electromagnetic field amplitude/energy and the number of excited photoelectrons?

In short, the answer is that energy in the electromagnetic field of frequency $f$ is quantized in units of $hf$. For a unity quantum efficiency photodetector the number of photoelectrons is equal to

$$

N = IAT/hf

$$

where

- $N$ is the number of photoelectrons,

- $I$ is the incident optical intensity (in units of $\text{J}/\text{m}^2/\text{s}$, for example),

- $A$ is the detector area (in units of $\text{m}^2$, for example),

- $T$ is the exposure time (in units of $\text{s}$, for example),

- $h$ is Planck's constant, and

- $f$ is the optical frequency of the incident light.

The number of photoelectrons is exactly equal to the number of quanta absorbed from the electromagnetic field. I think it is helpful to see the answer up front, however, below, I will give a more thorough discussion of the photoelectric effect.

The Photoelectric Effect

The OP requested "I would like to know how to define a hypothetical transformation $T(E(t,x))=478$ explained in terms of waves of the EM field, not in terms of photons (assuming that is even possible).". As seen above, it is not possible to give the complete story without making reference to the quantization of the energy fo the electromagnetic field. Because of this we will go into some detail about the photoelectric effect, so consider researching that further if necessary.

Below we will discuss the photoelectric effect as it pertains to the ejection of electrons from a metal. The basic ideas will carry over to the excitation of bound electrons from their valence bands into the conduction bands in the semiconducting photodetector.

For an electron to be excited, it is necessary for the electron to absorb energy from the electromagnetic field. For monochromatic light (of sufficiently high frequency), it is the case that the number of electrons excited (number) is proportional to the integrated optical energy over the detector active area and the exposure time. The integrated optical energy is the product

$$

E = IAT

$$

where $I$ is the optical intensity, $A$ is the detector area, and $T$ is the optical exposure time.

However, surprisingly from the point of view of classical physics, if you vary the frequency of the incident electromagnetic radiation, you find that the number of photoelectrons generated has a non-trivial dependence on the frequency.

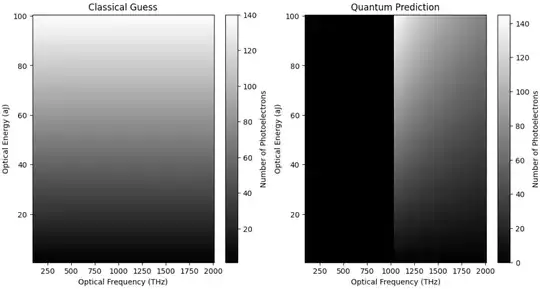

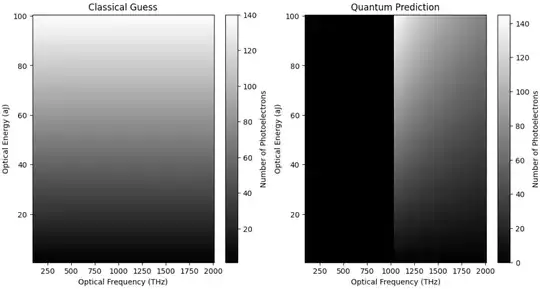

Consider illuminating a metal surface with electromagnetic radiation of a given frequency $f$ (specified in THz) and with a given integrated energy $E$ (specified in $\text{aJ}$, attojoules). Below I show a crude classical prediction for the number of ejected electrons and the quantum prediction for the number of ejected electrons.

Classically, we may have expected the plot on the left. We may have expected that as we increase the integrated energy that the number of photoelectrons increases linearly and that the number of photoelectrons is independent from the incident optical frequency. However, in experiment, we see the plot on the right. We see that below a certain cutoff energy (10.4 THz in this case, stolen from the Wikipedia page example for Zn) no photoelectrons are ejected. Above the cutoff frequency we see that increasing the integrated energy does increase the number of photoelectrons, however, the conversion factor between integrated energy and number of photoelectrons varies with wavelength.

Indeed, the interpretation here, provided by Einstein in 1905, is that the energy of the electromagnetic field is quantized in units of $hf$ where $h$ is Planck's constant and $f$ is the optical frequency. The idea is that an electron can absorb at minimum one quanta $hf$ of energy from the electromagnetic field. In this case if the integrated energy is $E$ then the number of photoelectrons is given by

$$

N = E/hf = IAT/hf

$$

Note that the cutoff frequency $f_{\text{cutoff}}$ is related to a minimum energy $\phi = hf_{\text{cutoff}}$ necessary to eject an electron from the metal. If an electron absorbs $hf$ energy then the excess energy $hf - hf_{\text{cutoff}}$ shows up as kinetic energy of the electron.

I claim that it is highly unlikely for $n$ quanta of energy $hf$ from the electromagnetic field to excite $m$ electrons from the material unless $n=m=1$. A convincing discussion of this is beyond the scope of this answer. For purposes of this answer we will assume that one electron is always excited as a result of absorbing $hf$ energy from the electromagnetic field, noting that some of the energy goes to unbinding the electron and the leftover energy appears as kinetic energy.

The conclusions from this sections are

- The energy of the electromagnetic field is quantized into units $hf$

- Exactly one electron is always excited by exactly one quanta $hf$ of energy from the electromagnetic field

- If the incident intensity is $I$, the photodetector has area $A$, and the exposure time is $T$, then the integrated optical energy on the photodetector is $E=IAT$

- The number of excited electrons is the integrated energy $E=IAT$ divided by the energy quanta $hf$: $N = IAT/hf$.

Finite Quantum Efficiency

Note that in practice it is not the case every quanta $hf$ from the integrated optical energy $E$ will cause an excitation of a photoelectron. There may be a variety of mechanisms by which optical energy does NOT result in photoelectron generation.

- The light may fall on a region of the detector which does is not optically active

- The light may be absorbed by some other mechanism than direct photoelectron generation (for example generating thermal excitations)

- The light may reflect from the optical surface

- etc.

These effects are captured by the photodetector quantum efficiency

$$

0 < \epsilon_Q < 1

$$

Taking into account sub-unity quantum efficiency, the number of excited photoelectrons is calculated by

$$

N = \epsilon_Q I A T / hf

$$

Counting Photoelectrons

The rest of the conversion from optical fields to digital counts is essentially classical electronics.

As discussed previously, the photoelectrons where excited into the semi-conductor conduction band and swept by the bias field into a storage region. Each pixel can hold a maximum number of photoelectrons before the photoelectrons start "falling out" of the storage region. I think of this as a bucket overflowing. The number of photoelectrons that can be stored before the bucket starts overflowing is related to the well-depth of the pixel, or the integrated energies at which we start to see effects like pixel saturation, bleaching, or bleeding. We will assume we are operating well below this point in the linear operating regime of the photodetector.

In a CCD sensor the "buckets" of pixels are shuttled around the sensor using various gating sequences to carry the buckets of electrons around the sensor. Eventually this "dance" delivers the electrons to a charge to voltage converter. One simple way to model this is that the charges are collected onto a capacitor. The capacitor then produces a voltage $V = Q/C = Ne/C$ where $N$ is the number of photoelectrons, $e$ is the electron charge, $Q=Ne$ is the total charge, and $C$ is the capacitance.

This voltage can then be read out on an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) which takes an analog voltage $V$ and converts it to a binary representation of an integer value. If the ADC has a maximum voltage $V_0$ and $d$ bits then the ADC value reading for $V$ will be

$$

D = \text{floor}\left(V/V_0 \times 2^d\right)

$$

I might have an off-by-one error in this formula.

Note that, in practice, between the charge storage and the ADC, there will likely be a charge and/or voltage amplifier to boost the otherwise tiny electrical signals. We will signify the combined gain of these stages by $G$ so that the voltage $V$ input at the ADC is given by

$$

V = GNe/C

$$

Putting it all together

Starting to put it all together. We can now start putting formulas together to get from properties of the incident electromagnetic field to the digital counts recorded by a camera pixel.

\begin{align*}

D =& \text{floor}\left(V/V_0\times2^d\right)\\

=& \text{floor}\left(GNe/CV_0\times 2^d\right)\\

=& \text{floor}\left(\frac{\epsilon_Q IAT}{hf}\frac{Ge}{CV_0}2^d\right)

\end{align*}

This is essentially the final answer except we can do one more step of work relating the incident intensity $I$ to the electric field amplitude $\mathcal{E}$. For linearly polarized light, the optical intensity $I$ is related to the electric field amplitude $\mathcal{E}$ by

$$

I = \frac{\epsilon_0 c}{2} |\mathcal{E}|^2

$$

where $c$ is the speed of light and $\epsilon_0$ is the permittivity of free space. For circular or elliptically polarized light you may need to take some care thinking about how exactly you define the electric field amplitude to get the pre-factor on this formula right.

We can finally put everything together to get the final result

$$

D = \text{floor}\left(\frac{\epsilon_0c}{2}|\mathcal{E}|^2\frac{\epsilon_Q AT}{hf}\frac{Ge}{CV_0}2^d\right)

$$

where

- $D$ is the digital value output on the camera pixel,

- $\epsilon_0$ is the permittivity of free space,

- $c$ is the speed of light,

- $\mathcal{E}$ is the electric field intensity,

- $\epsilon_Q$ is the detector quantum efficiency,

- $A$ is the pixel area,

- $T$ is the exposure time,

- $h$ is Planck's constant,

- $f$ is the optical frequency of the incident light,

- $G$ is the combined charge and voltage gain in the CCD sensor,

- $e$ is the electron charge,

- $C$ is the charge-to-voltage converter capacitance,

- $V_0$ is the ADC reference voltage and

- $d$ is the bit-resolution of the ADC.

Some further notes/disclaimers

Note that this is in some ways a very crude model of the CCD sensor detection chain. Many of the details have probably been botched with respect to how actual CCD sensors work. However, I think this crude model does capture many of the important features and at least gives a gist for the physics/signal processing happening and also gives a satisfactory answer to this question.

Also note that, in more detailed theory, the relationship between the incident optical intensity and the number of photoelectrons is actually a statistical relationship involving Poissonian shot noise. That is, for the same incident optical field but with repeated exposures, you will get different numbers of photoelectrons and different number of digital counts. This is related to "fundamental" quantum randomness. However, if the intensity is high enough, the signal-to-noise ratio becomes very good and we can ignore the statistical uncertainty in the number of photoelectrons. Also, unless the application is highly technical, it is likely the case the electronic noise from the amplification stages dominates quantum shot noise.

Direct answers to questions in the OP

I know that a camera does not directly measure the immediate value of the electromagnetic field's vector, but rather the average value of a derived quantity (a statistic of the EM field). Perhaps this quantity is the light's Intensity $[W/m^2]?$

The value recorded for a pixel is related to the intensity of the electromagnetic radiation incident on that pixel during the exposure time. The recorded value is proportional to the intensity on the pixel $I$, the pixel area $A$, and the exposure time $T$.

By the way, does the camera measure the intensity of the electric field alone, or the intensity of the magnetic field alone, or the sum of both the electric and the magnetic component?

The photoelectrons are technically excited by the electric field from the incident electromagnetic radiation. For this type of photoexcitation, the magnetic field is irrelevant. It is worth noting, as an aside, that the energy in electromagnetic radiation in free space is evenly split between electric and magnetic energy, so if you know any of the electric energy, the magnetic energy, or the electromagnetic energy you can figure out the other two.

How can I mathematically describe the relation between the underlying EM field and the final pixel value?

...

I would like to know how to define a hypothetical transformation $T(E(t,x))=478$ explained in terms of waves of the EM field, not in terms of photons (assuming that is even possible).

See the formula above as the main part of this answer. But note that we couldn't avoid a discussion of the quantization of the electromagnetic field energy. I gave the entire answer above without using the word "photon" because that word can be problematic. My definition of a "photon" is "a quantized excitation (of energy $hf$) of the electromagnetic field". In the description above you can easily see where I could have instead used the word "photon". For example, we can summarize the relationship between the number of photoelectrons and the incident electromagnetic radiation by saying "The number of photoelectrons is equal to the number of photons collected on the detector with area $A$ during exposure time $T$ multiplied by the detector quantum efficiency $\epsilon$". I will note that my definition of photon is still in terms of the electromagnetic field. This is contrasted with other definitions which involve the idea of a particle. I think my definition is better suited to answer what was requested in this question.

P.S. If there are any books, papers or blogposts that explain this topic in more detail, please share a link. Thank you.

The Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy, Third Edition edited by James Prawley has an excellent appendix titled "More Than You Ever Really Wanted To Know About Charge-Coupled Devices" which explains much of what is described in this answer in better detail. You may be able to find it online. I highly recommend this as a resource. There is a lot that I wanted to know about CCDs but, true to the title of this appendix, it has more info than even I wanted to know!