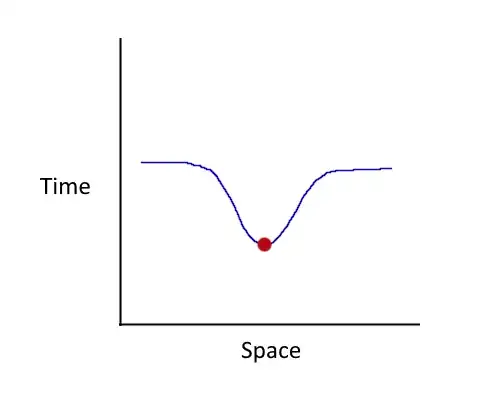

Here is a simple 2D diagram of 4D spacetime, showing curvature caused by a massive object, as it's commonly depicted:

Here we see based on the diagram that the object is "back in time" compared to the surrounding area where the curvature is less dramatic. This statement on its own would seem correct, as we know massive objects slow time, causing the object to "fall behind" in its time compared to less massive objects. However, this whole depiction is not correct-- it can't be correct-- as if it were accurate it would mean one of two things: either the massive object would move "down" in the time dimension relative to the surroundings as the discrepancy between the clocks of the massive object and the surrounding area grew further and further out of sync, causing the spacetime curvature of the massive object to increase over time, or, time won't move at any different rate for the massive object, it will simply be offset or out-of-sync by a certain amount, given by the vertical offset in the graph.

Neither of these descriptions match observed reality, so the depiction must be wrong. The problem seems to be in depicting spacetime curvature as an offset in the time coordinate. We understand that it's not the point in time that's offset by spacetime curvature, but the rate of time.

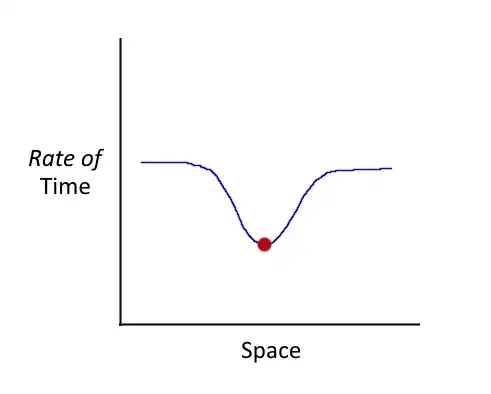

Given that, here's a simple correction to the diagram:

This change seems to align the common visual with observed reality, but there is another problem: "rate of time" isn't a physical dimension, right? The fourth dimension we talk about is always labelled time, not "rate of time," and a rate of something can't be a physical dimension, right?

I have until now always understood spacetime curvature as curvature "into" the time dimension, but is that simply untrue? Or at least in the simple sense? What is going on exactly with spacetime curvature then?