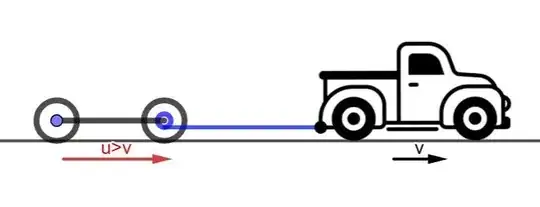

If we have a condition, when the truck moves forward with velocity $v$, the wheel of the trailer rotates $n$ times in time $t$, it follows that the amount of rope wound onto the spool in time $t$, is $2 \pi r \times n$ where $r$ is the radius of the inner spool. Therefore the velocity $u$ of the trailer must be the velocity of the truck or the rope plus the amount of rope that is wound in, in time $t$:

$$u = v + \frac{2 \pi r n}{t}. \tag{1}$$

The spool and the wheel rim must rotate the same number of times $(n)$ in a given time so the velocity of the trailer can also be described by:

$$u = \frac{2 \pi R n}{t}, \tag{2}$$

where $R$ is the outer radius of the trailer wheel. Equating $(1)$ and $(2)$ to each other gives us:

$$v + \frac{2 \pi r n}{t} = \frac{2 \pi R n}{t} $$

$$\rightarrow v = \frac{2 \pi (R-r) n}{t}. \tag{3}$$

Dividing equation $(2)$ by $(3)$ gives us the ratio:

$$\frac uv = \frac{1}{(1-r/R)}$$

$$\rightarrow u = \frac{v}{(1-r/R)}. \tag{4}$$

This result implies that as $r$ approaches $R$, the ratio $u/v$ is unlimited. This bothered me at first until it occurred to me that when $r=R$, equation $(3)$ tells us $v=0$, so when $r=R$ the result of equation $(4)$ is $0/0$ which is undefined. The reason $v$ goes to zero is because the equations assume a no slipping condition and the only truck velocity that can satisfy that condition when $r=R$ is zero. When $r=R$ the trailer wheel must slip without rotating if the truck has a non-zero velocity.

==============================================================

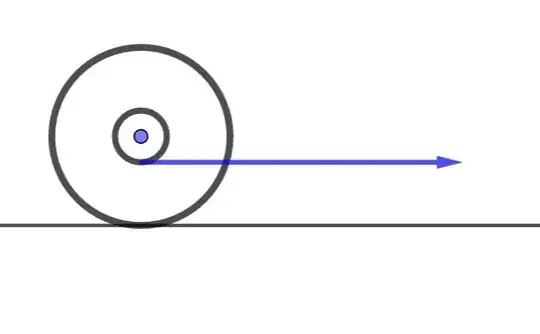

That takes care of the quantitative mathematical aspect. Qualitatively, when the truck is going to the right, the road friction applies a torque that tries to turn the wheel clockwise and the rope applies a torque that tries to turn the spool counter-clockwise. The lever arm $R$ of the road friction torque is greater than the lever arm of the spool $r$, so the road friction torque dominates and the spool and wheel must turn clockwise. Since the spool is winding in rope, the spool and the trailer must be going faster than the rope and the truck. The difference in radii gives us a mechanical advantage and the whole system acts as a geared system, that trades high torque and low rpm for low torque high rpm and speed. The power in, is equal to the power out (when ignoring friction losses), so there is no violation of the energy conservation principle.

To convince myself that the equations are valid, I constructed this GeoGebra construction to make sure everything works out as it should. To use the simulation, just slide the time slider to the right. The ratio of $r$ to $R$ can be adjusted with another slider.

With a bit of imagination, the above mechanism can be applied to the wind-powered land vehicle that goes faster directly downwind than the wind propelling it. See this Veritasium video or this. The vehicle has a propeller with an adjustable pitch and also a chain drive with its own gear system and together they provide a geared system that can multiply the speed of the input force (the wind) at the cost of having low torque and slow acceleration.