In this electromagnetism class, professor derives Faraday's law from a very specific case (he specifies Faraday's law is a kind of axiom in physics, but that in this very special configuration, one can "derive" it).

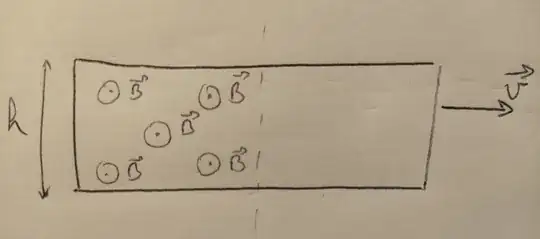

The configuration is: we have a zone where there's a constant magnetic field going out of the screen, a closed circuit is half immersed in this zone and someone is pulling the circuit out of the zone (towards the right) with a velocity $\vec{v}$.

Professor computes the Lorentz force on the electrons of the left leg of the circuit (there's no $\vec{E}$ term in the Lorentz force, since we are in magnetostatics). After integrating it over all the circuit, he finds $hBv$.  Similarly he finds that $$-\frac{d\phi_B}{dt} = hBv $$

.

Similarly he finds that $$-\frac{d\phi_B}{dt} = hBv $$

.

My question is: why didn't he also consider the Lorentz force on the cations of the left leg (they are moving too)?

Said slightly differently, I'm wondering whether we should consider the Laplace force for the term traditionally on the left-hand side of the Faraday's law or consider solely the Lorentz force on negative charge carriers?

My understanding of the Laplace force is that in this case, the Laplace force term due to the electrons cancels out with the Laplace force term due to the cations (because of charge neutrality).

So to sum up either the LHS of Faraday's law concerns the Laplace force (in this case there is no way to derive Faraday's law from any special configuration), either we consider only the Lorentz force of the negative charge carriers in Faraday's law (this possibility seems dubious, why would negative charge carriers be given such a special treatment?).

EDIT:

My understanding of this situation is that the changing magnetic flux creates an EMF, which in turn creates a current (some would call it induced current), which from Laplace force exerts a force on the circuit towards the left (opposing the pulling force "someone" exerts on the right). But in no way (from my opinion) this configuration allows us to "derive" Faraday's law.