Just to give you a partial answer that I hope is somewhat instructive, I want to point out that length contraction doesn't always happen in relativity, and especially with moving objects.

And one of your objects, is light: it is the thing that can't stop moving, in this theory.

Suppose that I am in a spaceship occupying some inertial reference frame and I think that there is a space rock moving past me that is 1 km long. And it is zooming by at $\gamma = 2$ and I have to clarify that it is 1 km long in my frame of reference, but due to length contraction it is 2km long in its frame.

Now you come along with $\gamma=2$, what do you see?

Well, it depends on which direction you're going!

If you're coming in opposed to the motion of the rock, then to you it contracts further, looking (2/7) km long. Note that if I furnished a 1km measuring stick that happened to be instantaneously next to the rock for me (but stationary), it would on your account be significantly longer than the rock, 0.5 km as compared to 0.28 km, as it wouldn't get contracted by as much.

But if you're coming in moving in the same direction as the rock, for you it de-contracts to its rest length of 2 km, meanwhile my measuring stick is still only 0.5 km long.

This is all to say that if you were thinking of some sort of homogeneous isotropic length contraction, that's definitely not what we're describing here!

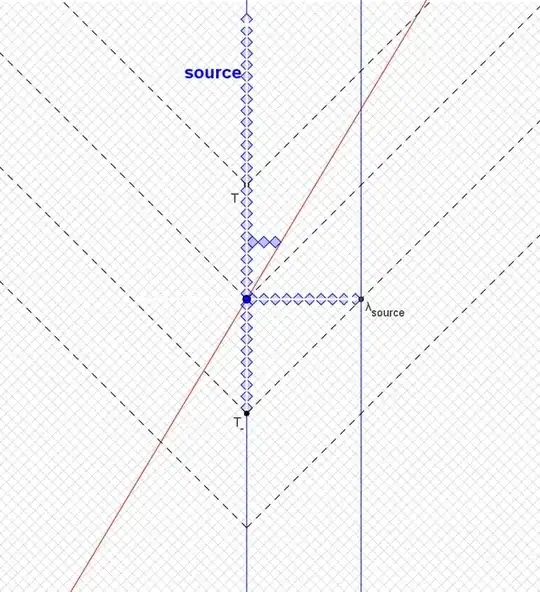

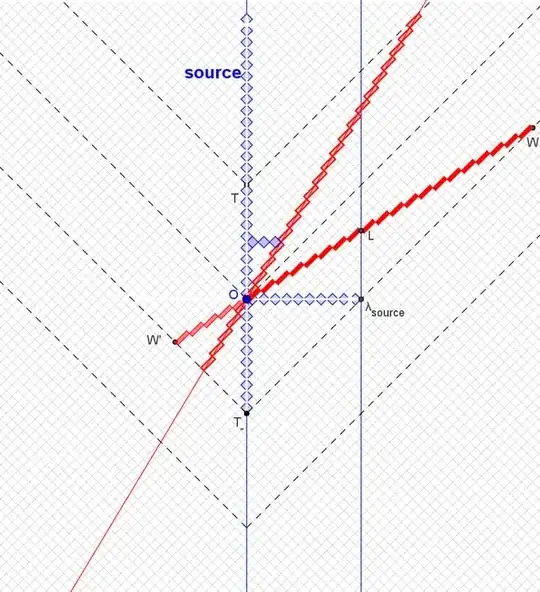

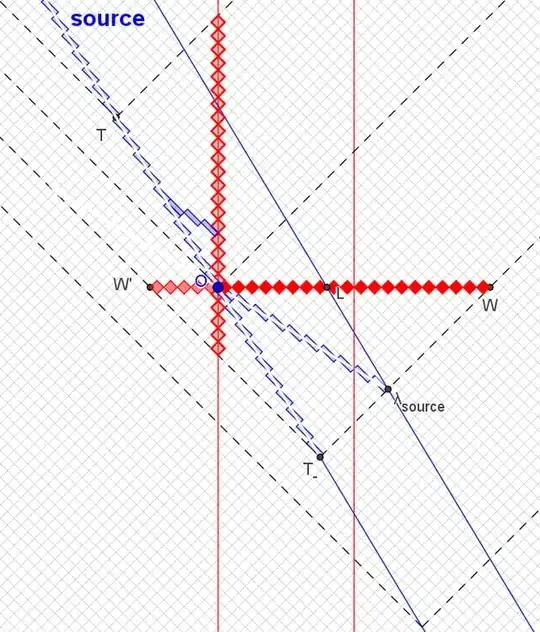

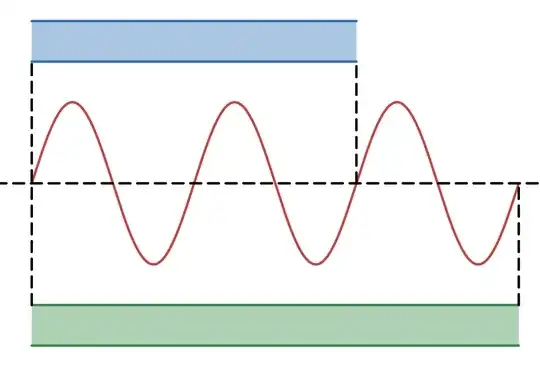

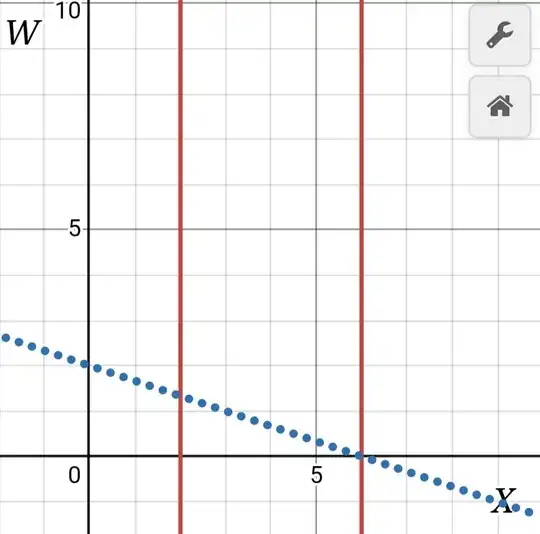

In terms of actually understanding it, I think different students require different insights before they suddenly “get it.” For me the insight was that the two edges of a rigid body form parallel lines on a spacetime chart $x$ vs $w=ct$, and those do Lorentz-transform to other parallel lines, and as they “tilt” they kind of “crowd together” while as they “untilt” they spread apart, this felt very unintuitive. But my “aha” that made it all click for me, was to look in the rest frame where the two lines are maximally un-tilted, they are in the $\hat w$-direction. And then I thought, “because of the relativity of simultaneity, moving observers have a present which is not in the $\hat x$ direction, and so they draw the diagonal line of “now” between these two lines at some angle, why don't they see the distance between the two as longer?” So the diagram that makes it click for me looks like this:

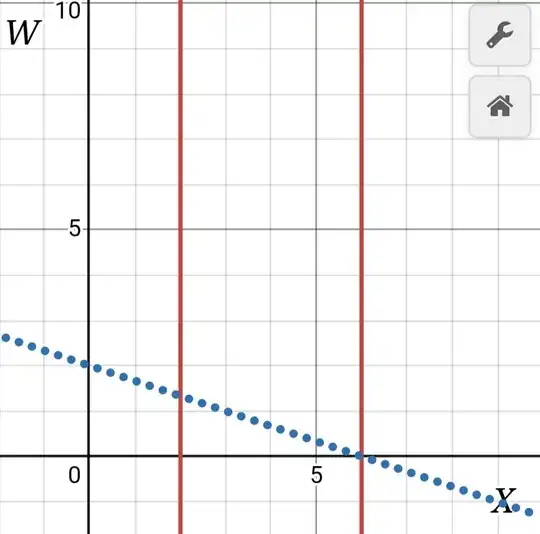

And the question is, why isn't that dotted blue line longer than the, in this case, 4 units between the two lines. And that is entirely due to the Lorentzian shape of the metric, it's $$\Delta s^2 = \Delta x^2 - \Delta w^2,$$ so the diagonal in this direction actually reduces the measured length commensurately.

So that meant a lot to me and probably doesn't mean so much to you! But just keep working problems in relativity and you will eventually find a perspective that clicks.