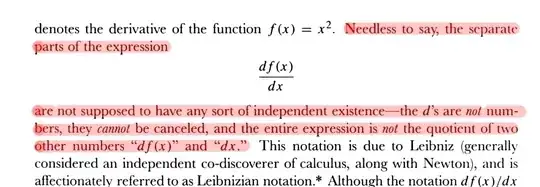

So I didn't encounter differentials that often until now, I was taught that the seperate parts of $dy/dx$ for example are not supposed to have any sort of independent existence - ok.

(Calculus, 4th edition, p. 155, Spivak)

Then I've found the following mathematical representation of Plank's distribution law (in Physical Chemistry: A Molecular Approach, Chapter 1, McQuarrie):

$$d\rho(\nu, T) = \rho_\nu(T) d\nu = \frac{8\pi h \nu^3}{c^3} \frac{d\nu}{e^{\frac{h\nu}{k_B T}} - 1}$$

With $d\rho$ and $d\nu$.

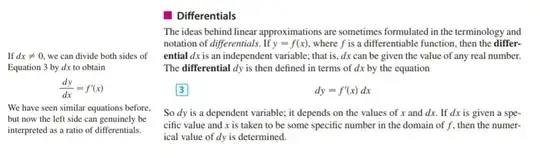

So I've read up about differentials in Stewarts Calculus Book which gives following definition:

$$dy = f'(x) \cdot dx$$

If I think about planck's law in those terms, my "$f'(x)$" would equal:

$$\rho_\nu(T) = \frac{8\pi h \nu^3}{c^3} \frac{1}{e^{\frac{h\nu}{k_B T}} - 1}$$

right? So to get a better understanding about what is changing and not only how it changes I thought about what $f(x)$ might be? So integrating $\rho_\nu(T)$ (computer calculated):

$$\rho(T) = \frac{8 \pi^5 k_B^4 T^4}{15 h^3 c^3}$$

Is this a more fundamental formula on the way to planks law? One which Planck used to further deriver his formula, which was there further at the beginning?

I have generally a problem to inteprete all of this in terms of physics (and maybe also mathematically), I would really appreciate if someone could clear things up and tell me if my thoughts are even correct.

I first thought $dx$ and $dy$ must be especially small but they can actually be any real number if we treat them like that (separated):

(Calculus, 8ed, James Stewart, p.190)

And sorry if this belongs more in math stackexchange.

Edit: I would also appreciate some book recommendations about the problem of dy/dx and dy, dx notation and how to interprete it correctly. Maybe then I could interprete the above formulation of the Distribution law better.