I've just started to learn lagrangians through this video and I'm a bit confused. The setup has that $L = T-V$. With $T=\tfrac{1}{2}mv^2$ and $V=mgx$. So, $L= \tfrac{1}{2}m(dx/dt)^2-mgx$. This is all good. He then calcualtes $d/dt (dL/dv)-dL/dx$ which is where it gets confusing for me. He writes that $dL/dx = -mg$. But if we are differentiating with respect to $x$, which is really just a function of $t$, aren't we really differentiating with respect to $t$? But then this means that $T$ shouldn't reduce to $0$ right? There's an analagous case for $dL/dv$. I think I'm probably messing up the definition of a derivative or something but clarification on this matter will be great.

When computing the Euler–Lagrange equations, why do we assume the coordinates do not depend on time?

3 Answers

Consider a function $F$ of two variables $a$ and $b$: $$ F(a,b)\;, $$ where the usual notation of parentheses and a comma indicates that $F$ is a function of two independent variables, $a$ and $b$.

Consider, for concreteness, an explicit example such as: $$ F(a, b) = a + b^2\;. $$

We write the partial derivative with respect to the first independent variable as $$ \frac{\partial F}{\partial a} = 1\;. $$

We write the partial derivative with respect to the second independent variable as $$ \frac{\partial F}{\partial b} = 2b\;. $$

Nothing in the above discussion can stop me from evaluating the function $F(a,b)$ at the values $a=x(t)$ and $b=\dot x(t)$. Indeed, nothing can stop me from writing: $$ F(x(t),\dot x(t)) = x(t) + \dot x(t)^2\;. $$

If I would like, I can also proceed to consider the integral: $$ G[x] = \int_{t_1}^{t_2} dt F(x(t), \dot x(t))\tag{1}\;, $$

Setting the variation of the integral in Eq. (1), with respect to the path $x(t)$, equal to zero results in the equation: $$ \left.\frac{\partial F}{\partial a}\right|_{a=x(t), b=\dot x(t)} - \frac{d}{dt}\left.\frac{\partial F}{\partial b}\right|_{a=x(t), b=\dot x(t)} = 0\;,\tag{2} $$ which is the Euler Lagrange equation for this system.

To be even more explicit about the variation of $G$ with respect to the function $x(t)$, I will explicitly write: $$ G[x+\epsilon w] = \int_{t_1}^{t_2} dt F(x(t)+\epsilon w(t), \dot x(t) +\epsilon \dot w(t))\;,\tag{3} $$ where $\epsilon$ is a "small" constant and $w(t)$ is arbitrary function, other than being constrained by the condition that $w(t_1) = w(t_2) = 0$.

Expanding the RHS of Eq. (3) to first order in epsilon gives: $$ G[x+\epsilon w] = G[x] + \epsilon\int_{t_1}^{t_2} dt \left( w(t)\left.\frac{\partial F}{\partial a}\right|_{a=x(t), b=\dot x(t)} + \dot w(t)\left.\frac{\partial F}{\partial b}\right|_{a=x(t), b=\dot x(t)} \right) +O(\epsilon^2) $$ $$ =G[x] + \epsilon\int_{t_1}^{t_2} dt w(t)\left( \left.\frac{\partial F}{\partial a}\right|_{a=x(t), b=\dot x(t)} - \frac{d}{dt}\left.\frac{\partial F}{\partial b}\right|_{a=x(t), b=\dot x(t)} \right) +O(\epsilon^2)\;. $$

Thus, the variational derivative of $G$ with respect to the curve $x(t)$ is zero when Eq. (2) above holds. And, as I already noted, Eq. (2) above is the Euler Lagrange equation for this system.

- 27,235

This is something I recently had to grapple with, so I hope I have this right.

The Euler-Lagrange formula is the general solution a path which extremizes an action (the integral of the Lagrangian). If a physical system admits a Langrangian, then its solution is the Euler-Lagrange formula. For the problems Lagrange was looking at, this is a natural sort of maximization problem.

William Hamilton later noticed that if you choose the Lagrangian $L=T-V$, then the resulting Euler-Lagrange formula is the 2nd order differential equation defined by Newtonian physics. The fact that $x$ and $\dot x$ can vary independently is less of a physically meaningful statement, and more just the way a Newtonian physics problem looks when you rewrite it in the form of a stationary action.

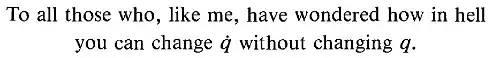

And yes, its strange. If I may quote an answer from the question Qmechanic linked, I can point out that you're not the first to find this to be strange, nor the last. This is the forward from "Applied Differential Geometry". By William L. Burke

- 53,814

- 6

- 103

- 176

Quoting from your question:

But if we are differentiating with respect to x, which is really just a function of t, aren't we really differentiating with respect to t?

In my opinion the problem here is confusing notation.

In the case the exposition in the video that you link to (Michel van Biezen), here is the differentiation that actually accomplishes the goal:

with $h$ as height:

$$ \frac{d(\tfrac{1}{2}mv^2)}{dh} - \frac{d(-\int_{h_0}^h \ F \ dh)}{dh} \tag{1} $$

Here the symbol $h$ is used to represent height coordinate generically.

(As we know: potential energy is defined as the negative of the integral of Force with respect to height coordinate: $-\int_{h_0}^h \ F \ dh$ )

The differentiation of the Lagrangian is differentiation with respect to the direction of the variation, and in this case the direction of the variation is the vertical direction: the height.

In this case the potential energy is mass times gravitational acceleration times height.

with $V$ for the potential energy:

$$ V(h) = mgh \tag{2} $$

Hence:

$$ \frac{dV(h)}{dh} = mg \tag{3} $$

If in the above the symbol $x$ would be used instead of $h$ then there is risk of confusion, as sometimes plain $x$ is used as shorthand for $x(t)$, where $x$ is a function of $t$.

Returning to (1): I must explain this notation, of course:

$$ \frac{d(\tfrac{1}{2}mv^2)}{dh} \tag{4} $$

In the following the left hand side is the same as (4), and the right hand side is the notation as used in the Euler-Lagrange equation:

$$ \frac{d(\tfrac{1}{2}mv^2)}{dh} \quad \Leftrightarrow \quad \frac{d}{dt}\frac{d(\tfrac{1}{2}mv^2)}{dv} \tag{5} $$

The above two differentiations are the same differentiation, what sets them apart is the order of operations.

To demonstrate (5):

Restating (4) in Leibniz notation, using $x$ for position coordinate:

$$ \frac{d(\tfrac{1}{2}m(\tfrac{dx}{dt})^2)}{dx} \tag{6} $$

Apply the chain rule, and write the result in Leibniz notation for the chain rule: a product of two differentations:

$$ \frac{d(\tfrac{dx}{dt})}{dx} \cdot \frac{d(\tfrac{1}{2}m(\tfrac{dx}{dt})^2)}{d(\tfrac{dx}{dt})} \tag{7} $$

The differentiation operator can be collapsed:

$$ \frac{d(\tfrac{dx}{dt})}{dx} \Rightarrow \frac{d}{dt} \tag{8} $$

Then (7) can be restated as follows:

$$ \frac{d}{dt} \frac{d(\tfrac{1}{2}m(\tfrac{dx}{dt})^2)}{d(\tfrac{dx}{dt})} \tag{9} $$

Which is according to the term for the kinetic energy in the Euler-Lagrange equation.

$$ \frac{d}{dt} \frac{d(\tfrac{1}{2}mv^2)}{dv} \tag{10} $$

This way of demonstrating (5) is abuse of notation, of course. It's a shortcut for sure, but the relation itself is correct.

Returning to the first notation:

$$ \frac{d(\tfrac{1}{2}mv^2)}{dh} - \frac{d(-\int_{h_0}^h \ F \ dh)}{dh} \tag{11} $$

The point is: the two energies, kinetic and potential, must be subjected to the same differentiating operation.

- Potential energy and kinetic energy both have dimensions of length squared divided by time squared: $L^2/T^2$

- Force and acceleration both have dimensions of length divided by time squared: $L/T^2$

The length dimension corresponds to the position coordinate. So, in order for the respective terms in the equation to remain dimensionally the same both energies must be differentiated with respect to the position coordinate.

- 24,617