Here are some more reasons a light signal from Earth must be able to reach and pass the Hubble Horizon.

The total velocity of a photon is given by its peculiar velocity and its recession velocity as seen from Earth: $$v_{\text{tot}} = v_{\text{rec}} +v_{\text{pec}}.$$

The peculiar velocity of a photon is the velocity measured by a local observer who is at rest with the bulk flow. To comply with SR and GR this is always measured to be $c$, so the total velocity of a photon moving away from Earth is $$v_{\text{tot}} = v_{\text{rec}} + c.$$

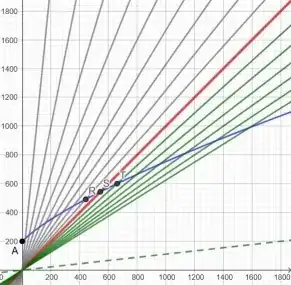

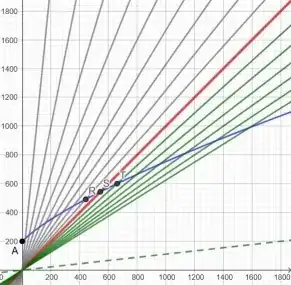

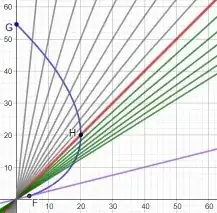

In the diagram above, the red worldline represents the Hubble Boundary and is where the expansion flow is equal to the speed of light. The green worldlines are those of galaxies outside the Hubble boundary that are receding at greater than the speed of light. The blue worldline is the trajectory of an outgoing photon. At event $\text{R}$ the total speed of the photon relative to Earth is $1.9c$ because the recession velocity is $0.9c$ at that location. It has no problem catching up with the boundary at event $\text{S}$, where the total velocity of the photon relative to Earth is now $2c$ and it easily continues on to catch up with the next Hubble flow object at $\text{T}$ which is 'only' moving at $1.1c$ relative to Earth. The dashed green line is the worldline of an galaxy receding at $9c$ and visually it looks like our photon could never catch up with that worldline, but if you zoom out using the scroll wheel of your mouse using the GeoGebra construction for that diagram you will see event $\text{N}$ where the photon overtakes that $9c$ object, despite the galaxies' extreme velocity relative to Earth. In fact the photon can catch up with any object with a finite constant velocity relative to us.

The above diagram assumes the scale factor as a function of time scales as per $a(t) = t$ which is a simple idealised model that assumes a empty universe with no gravity slowing down the expansion. In reality the scale factor is closer to $a(t) + t^{2/3}$ and the recession velocities curve slightly inwards as they gradually slow down due to gravity. This does not prevent the photon catching up with the boundary.

The FLWR metric for an expanding Universe taking only radial motion into account is $$ c^2 \mathrm{d}\tau^2 = c^2 \mathrm{d}t^2 - a^2(t) \ \mathrm{d}X^2$$ assuming a flat universe (and $k=0$) which is close to what our Universe appears to be. $X$ is a so called comoving coordinate. This is the distance from the Earth to a given galaxy at the current time. Despite the fact the galaxy is receding, the convention is that $X$ is deemed to be constant and independent of time. This is a bit weird but it is the convention used by cosmologists. $\dfrac{\mathrm{d}X}{\mathrm{d}t}$ is the motion of a particle relative to that fixed distance. Rearranging the metric we get: $$ a(t) \frac{\mathrm{d}X}{\mathrm{d}t} = \sqrt{c^2 - c^2 \frac{\mathrm{d}\tau^2}{\mathrm{d}t^2}}.$$

For a photon we set $\dfrac{\mathrm{d}\tau}{\mathrm{d}t} = 0$ and obtain the peculiar velocity of a photon in coordinates where the observer acknowledges the universe is expanding as $$ a(t)\frac{\mathrm{d}X}{\mathrm{d}t} = c.$$

The 'real' local peculiar velocity of a photon is always $c$ for any non zero value of $a(t)$ as it should be.

In coordinates where the observer considers distance $X$ to be fixed despite the fact the distance is really increasing over time in an expanding universe, the peculiar velocity of light is given by: $$\frac{\mathrm{d}X}{\mathrm{d}t} = \frac{c}{a(t)}.$$

In these coordinates the peculiar velocity of light appears to be slowing down over time. This is an artifact of treating the expanding distance as a constant value.

If a photon can travel the distance $X$ in the comoving coordinates where $X$ is considered fixed, it can also travel the distance $X'$, which is the corresponding distance where the distance is expanding over time. We can find out how far a photon can travel in a given time by integrating the last equation:

$$\Delta X = \int\limits_0^{\infty} \frac{c}{a(t)} \ \mathrm{d}t$$

which is infinite for any reasonable value of $a(t)$, e.g. $a(t) = t^{2/3}$ for a matter dominated universe or $a(t) = t$ for an empty universe. In other words, if a galaxy is at infinite distance from us right now, a photon sent from Earth right now will eventually arrive at that galaxy. If the Hubble boundary is at finite distance from us right now, a photon leaving now will have no trouble catching up with the expanding boundary in a finite amount of time, in any reasonable cosmological model. It works both ways. We can eventually see light from any object in the universe, no matter how far away it is now, and no matter how fast it is receding. This is for any fixed value of $a(t)$, even e.g. $a(t) = t^2$, so that recession velocities are proportional to time squared. In effect there is no event horizon if $a(t)$ is constant. However, if $a(t)$ is increasing over time there may be an event horizon.

In any reasonable model of the universe, arguments that an object has to be overtaken by the Hubble boundary in order for us to see them, are not correct. Just to be clear, there are objects outside the Hubble boundary that we do not yet see. Not enough time has elapsed since the beginning of the Universe for us to see them now. These objects are outside what is known as the particle horizon or the current 'visible universe'.

This diagram that might convince you if you are not already:

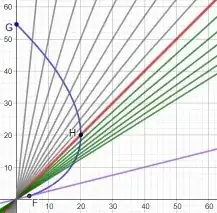

We are at $\text{G}$ and the blue curve is a cross section our past light cone. We can see everything that is on the surface of our past light cone. We see light now, that was emitted at event $\text{H}$ which was on the Hubble horizon. We also see light from event $\text{F}$ which was emitted by the object with the purple worldline which was moving at $4c$ relative to us. We are seeing light right now, from a superluminal object that was outside the Hubble horizon at the time it was emitted and which is still outside the Hubble horizon right now. Clearly there is no need for the light to be emitted when the object is inside the Hubble horizon.

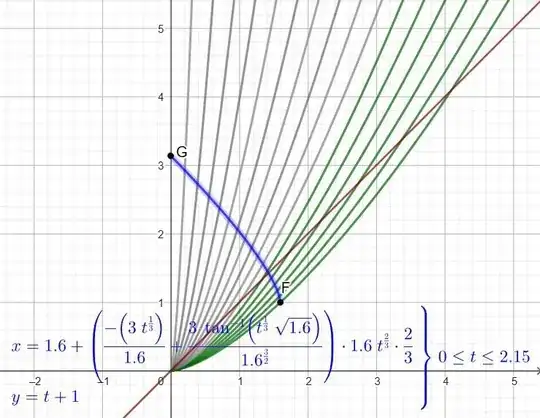

As pointed out by @Yukterez, in a matter dominated universe, worldlines of individual galaxies curve inwards due to gravity. In such a case, the purple worldline would eventually fall inside the Hubble boundary (which is not a physical boundary and so is not slowed down by gravity). However, we can see the purple galaxy long before it falls inside the Hubble boundary. This is better illustrated in the new chart below:

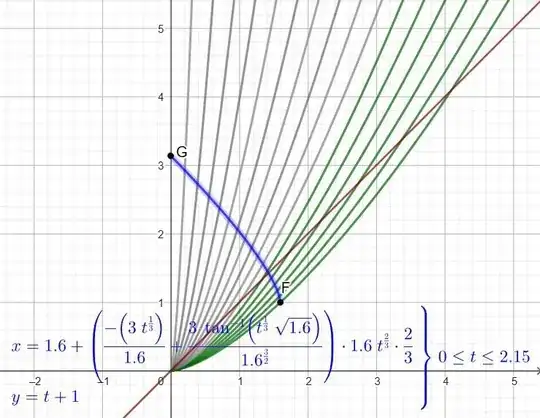

This is the chart updated to show a more realistic matter dominated universe with $a(t) = 2/3$, together with the parametric equation used to plot the blue worldline on the ingoing photon. The factor of $1.6$ that appears several times in the equation is the distance away the galaxy was at the time the light was emitted at one unit of time. It shows the outward flow of galaxies slowing down over time due to gravity and ending up inside the Hubble radius (red worldline). The photon emitted by the galaxy at event $\text{F}$ while it was outside the horizon still arrives at us at event $\text{G}$.