Stable mechanical equilibrium broadly means that any movement would incur a net energy penalty.

This is intuitive when we see a ball at rest in a dip, for example; it’s clear that any rolling would incur an increase in gravitational potential energy.

Even a ball hanging from a spring, for example, is straightforwardly analyzed; the string stretches until the benefit from dropping in a gravity field no longer pays for the increased strain energy in the string material.

How much additional strain energy? For objects being stretched, a stiffness $k$ corresponds to a restoring force of magnitude $F=k(\delta x)$ and a strain energy increase of $k(\delta x)^2/2$ for a small stretch $\delta x$. (Another way to look at this is that the effective stiffness at equilibrium corresponds to the curvature or second derivative of the energy landscape for small perturbations. A deeper minimum corresponds to greater stability.) What's more, if the object (now idealized as Hookean, i.e., linear elastic) is already preloaded by substantial stretching $x_\mathrm{preload}$, the strain energy increase from additional $\delta x$ is boosted to $$k\frac{(x_\mathrm{preload}+\delta x)^2}{2}-k\frac{x_\mathrm{preload}^2}{2}\approx kx_\mathrm{preload}\delta x\gg k\frac{(\delta x)^2}{2},$$ so the energy penalty to shifting away from equilibrium in the direction of preload can be made much more severe. (To complete the analysis for the other side of the energy curve, we'd consider the associated stiffness for a perturbation in that direction.) This is relevant to the discussion that follows.

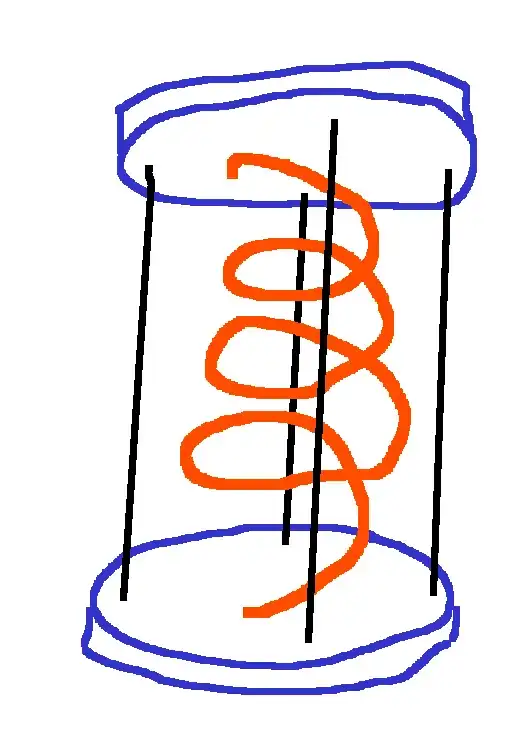

So-called tensegrity structures can be visually appealing because it’s not immediately clear what’s incurring the energy penalty; thus, objects seem to levitate—counterintuitively. Further, a mode of easy movement may seem obvious, and it’s interesting if that mode doesn’t activate.

In the picture, ignoring the chains for a moment, the white "strap" is perhaps loose and looks unstable—we'd expect the top to immediately rotate down and to the right. Ignoring the "strap," we know that chains have no compression strength—they can only pull, and so the table again seems destined to collapse. It emerges that the strap is actually an elastomer under large preloaded tension, not limited to the top's weight. The chains are actually preventing rising, twisting, and rotation, as any motion would stretch at least one of them and incur a large strain energy penalty. The larger the preloading, the stiffer the assembly.

(I am grateful to the commenters for identifying key aspects of this design.)