Sure! I think I'm qualified to answer, not because I used to teach heat transfer in a Chemical Engineering course, but because I raised four daughters!!

Air is an excellent thermal insulator. If you put it in direct contact with your hand, it cools down much faster. You will have the same effect emerging in water, however. If you put the bottle in a turbulent flow of water, it will cool down something like ten times faster. It will be too fast, though, because the liquid inside won't be cooling as fast. So you may also shake the bottle to speed the cooling inside.

To calculate the time for cooling from $60^\circ C $ to $40^\circ C $ of a baby bottle filled with milk in the air, both without convection and with high turbulent convection, we can use the lumped capacitance method. Here's a detailed approach:

To calculate the time for cooling from $60^\circ C $ to $40^\circ C $ of a baby bottle filled with milk in the air, both without convection and with high turbulent convection, we can use the lumped capacitance method. Here's a detailed approach:

1. Without Convection

In the absence of convection, heat transfer occurs solely through conduction and radiation. However, for simplicity, we'll consider negligible heat transfer in this scenario due to very high thermal resistance.

2. With High Turbulent Convection

For high turbulent convection, we use the given heat transfer coefficient.

Assumptions and Given Data

- Initial Temperature ( $ T_{\text{initial}} $): $60^\circ C $

- Final Temperature ( $ T_{\text{final}} $): $40^\circ C $

- Ambient Temperature ( $ T_{\text{ambient}} $): $25^\circ C $

- Density of Milk ( $ \rho $): $1000 \, \text{kg/m}^3 $

- Specific Heat Capacity ( $ c $): $4186 \, \text{J/(kg·K)} $

- Volume of Bottle: $0.25 \, \text{L} = 0.00025 \, \text{m}^3 $

- Surface Area of Bottle: $0.03 \, \text{m}^2 $

- Thermal Conductivity of Bottle: $0.6 \, \text{W/(m·K)} $

- Heat Transfer Coefficient for High Turbulent Convection ( $ h $): $100 \, \text{W/(m}^2\text{·K)} $

Calculations:

Mass of Milk:

$$

\text{Mass} = \rho \times \text{Volume} = 1000 \, \text{kg/m}^3 \times 0.00025 \, \text{m}^3 = 0.25 \, \text{kg}

$$

Time Constant for Convection:

$$

\tau = \frac{m \cdot c}{h \cdot A} = \frac{0.25 \, \text{kg} \times 4186 \, \text{J/(kg·K)}}{100 \, \text{W/(m}^2\text{·K)} \times 0.03 \, \text{m}^2} \approx 349.5 \, \text{s}

$$

Cooling Equation:

$$

T(t) = T_{\text{ambient}} + (T_{\text{initial}} - T_{\text{ambient}}) \exp\left(-\frac{t}{\tau}\right)

$$

$$

T(t) = 25 + (60 - 25) \exp\left(-\frac{t}{349.5}\right)

$$

Explanation of Results:

The values calculated will give us the time required to cool from 60°C to 40°C under high turbulent convection.

Let's run the calculations.

Calculation Results for Cooling Time

For cooling from $60^\circ C $ to $40^\circ C $ under high turbulent convection:

- Time Constant for Convection ( $\tau $): Approximately $ 349.5 \, \text{s} $

- Cooling Time: Approximately $ 299 \, \text{s} $ (or about 5 minutes)

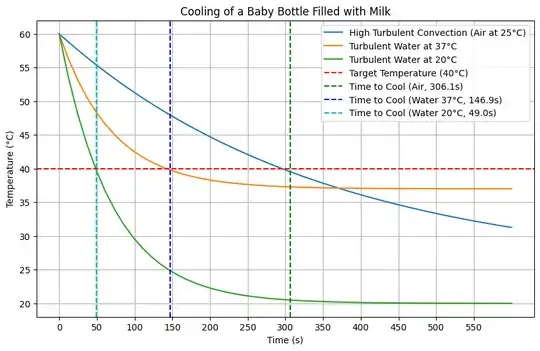

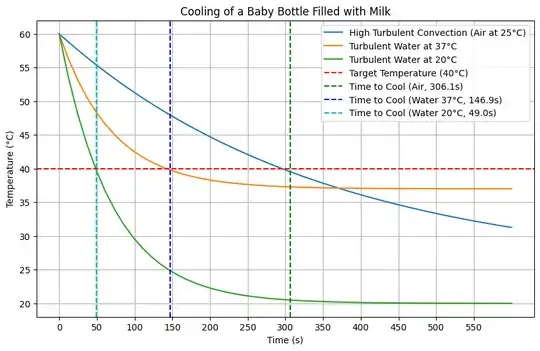

Cooling Time Comparison for Different Scenarios

Here are the results for the cooling times of a baby bottle filled with milk from $60^\circ C $ to $40^\circ C $ under different conditions:

- High Turbulent Convection (Air at 25°C):

- Cooling Time: Approximately 299 seconds (or about 5 minutes)

- Turbulent Water at 37°C:

- Cooling Time: Approximately 144 seconds (or about 2.4 minutes)

- Turbulent Water at 20°C:

- Cooling Time: Approximately 50 seconds (or about 0.8 minutes)

The great advantage of holding the bottle in your hand compared to placing it in running tap water, despite the body temperature being higher, is the possibility of causing agitation in the internal fluid, due to sudden movements.

When considering the convection parameters for cooling a baby bottle, you need to account for both the internal and external convection processes. Here’s how to approach the problem:

External Convection

External convection involves the heat transfer between the outer surface of the baby bottle and the surrounding air. The rate of heat transfer can be described by Newton's Law of Cooling:

$$ q = h_{\text{ext}} A_{\text{ext}} (T_{\text{surface}} - T_{\text{air}}) $$

where:

- $ h_{\text{ext}} $ is the external convective heat transfer coefficient.

- $ A_{\text{ext}} $ is the external surface area of the bottle.

- $ T_{\text{surface}} $ is the temperature of the bottle's outer surface.

- $ T_{\text{air}} $ is the ambient air temperature.

Internal Convection

Internal convection involves the heat transfer between the inner surface of the baby bottle and the fluid (milk or formula) inside. This can be described similarly:

$$ q = h_{\text{int}} A_{\text{int}} (T_{\text{fluid}} - T_{\text{surface}}) $$

where:

- $ h_{\text{int}} $ is the internal convective heat transfer coefficient.

- $ A_{\text{int}} $ is the internal surface area of the bottle.

- $ T_{\text{fluid}} $ is the temperature of the fluid inside the bottle.

- $ T_{\text{surface}} $ is the temperature of the bottle's inner surface.

Changing Convection Parameters

Including Internal Convection:

- Internal Heat Transfer Coefficient ( $ h_{\text{int}} $): This can be increased by promoting internal mixing, which can be achieved by shaking or stirring the fluid inside the bottle. Higher mixing rates generally increase the internal heat transfer coefficient.

- Fluid Properties: Changing the fluid’s viscosity and thermal conductivity (e.g., using a different liquid) can affect internal convection.

- Surface Area ( $ A_{\text{int}} $): This is typically fixed by the geometry of the bottle, but using a bottle with internal fins or a different shape can change the effective internal surface area.

Including External Convection:

- External Heat Transfer Coefficient ( $ h_{\text{ext}} $): This can be increased by improving airflow around the bottle. Using a fan or placing the bottle in a cooler with forced air circulation can help. Natural convection can also be enhanced by ensuring the bottle is not in a stagnant air environment.

- External Conditions: Increasing the temperature difference between the bottle’s surface and the ambient air (e.g., by cooling the air) can increase the heat transfer rate.

Ignoring Internal Convection:

- Assumption of Well-Mixed Fluid: If the fluid inside the bottle is assumed to be well-mixed, you might treat it as having a uniform temperature. In this case, the internal convection can be simplified to an effective thermal resistance.

- Negligible Internal Resistance: If the internal thermal resistance is very low compared to the external resistance, you can ignore the internal convection effects. This would be the case if the internal mixing is very effective.

To include or exclude internal convection in your calculations, you can use a thermal network approach with resistances in series:

Including Internal Convection:

$$ \frac{1}{R_{\text{total}}} = \frac{1}{R_{\text{int}}} + \frac{1}{R_{\text{wall}}} + \frac{1}{R_{\text{ext}}} $$

where:

- $ R_{\text{int}} = \frac{1}{h_{\text{int}} A_{\text{int}}} $

- $ R_{\text{wall}} = \frac{L}{k A_{\text{wall}}} $ (thermal resistance of the bottle material)

- $ R_{\text{ext}} = \frac{1}{h_{\text{ext}} A_{\text{ext}}} $

Ignoring Internal Convection:

$$ \frac{1}{R_{\text{total}}} = \frac{1}{R_{\text{wall}}} + \frac{1}{R_{\text{ext}}} $$

I am equating the hand firmly holding the bottle to being immersed in perfectly agitated water (approximating human blood as water). Obviously the analysis would have to be much more complex, for example approaching the human body with a heat exchanger with capillary tubes flowing at the speed of blood circulation. The complexity, however, may not compensate for the gain in accuracy obtained.

Much more important would be to know how to ensure turbulence inside the bottle to make it a perfect mix. I will tell you my technique.

I begin rotating the bottle to impress a rotation of the fluid inside. This flow, however, is laminar, so as soon as the flow reaches a steady state, I revert the direction of rotation.Reversing the direction of rotation will indeed disrupt the flow, causing some mixing.

I think it would be clever to introduce obstacles for the internal flow: Adding obstacles or irregularities inside the bottle can promote flow instabilities and turbulence. For example, small fins or ridges could create localized turbulent regions.Actually, some bottles have this feature.