I have been trying to understand and find some justification about why Hubble's Law needs to implicate any sort of relative motion between galaxies.

I can understand why and how one would explain the calculations of distances, as well as the expansion of space based on the observed measurements of redshifting.

These are all great and well supported.

But where did the idea of galaxies receding from each other come from? What is the evidence or indications that support this claim? Are we just assuming that if space is expanding between point A and B, that means the absolute distance between A and B is increasing? Why can't this just be a property of how light experiences the expansion of space for example?

4 Answers

Why can't this just be a property of how light experiences the expansion of space for example?

Because if light experiences it, we definitely do.

The way the Universe's expansion is most usually defined is int Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker metric, which describes a spacetime whose spatial components are dependent on a "scale factor" $a(t)$, which varies with time. Light rays experience this because the difference between the FLRW and flat Minkowski metric fundamentally change the geodesics that light follows, and so is the case for massive, slower-than-light objects.

By definition, this expansion of space causes objects to recede from one another, just because that's how space works. In FLRW spacetime, rulers shrink over time (assuming $a(t)$ is a strictly-increasing function), and the apparent distance between any two objects increases. It in fact increases at a rate proportional to distance, fitting the idea of Hubble's law well.

Say we have a laser that we use to measure distance. In one dimension (for simplicity), the FLRW metric is

$$\mathrm{d}s^2=c^2\mathrm{d}t^2-a(t)^2\mathrm{d}x^2.$$

Light travels between points and along geodesics where $\mathrm{d}s^2=0$. So, for a light ray,

$$c^2\mathrm{d}t^2=a(t)^2\mathrm{d}x^2,$$

which then of course gives

$$\frac{a(t)\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t}=c$$

essentially saying that light travels at the speed of light, of course.

But wait, there's an $a(t)$ term in there! In regular models of spacetime expansion, this function is always increasing with $t$: $\frac{\mathrm{d}a}{\mathrm{d}t}(t)>0$. If you properly express the differential on the right, you get

$$\frac{\mathrm{d}x}{\mathrm{d}t}=\frac{c}{a(t)},$$

suggesting that a light ray would appear to slow down as the universal expansion (indicated by $a(t)$) progresses. Of course, you can't ever observe light moving at a speed other than $c$ in reality, so the way this is explained is by the spatial distance increasing between points: the light didn't slow down to half the speed, the speed stayed the same, the distance between points just doubled.

Of course, in three spatial dimensions, this effect is isotropic: it happens everywhere, roughly uniformly. All light rays appear to slow down, and special relativity switches that to become "all distances increase over time".

And a change in distance over time is, by definition, velocity.

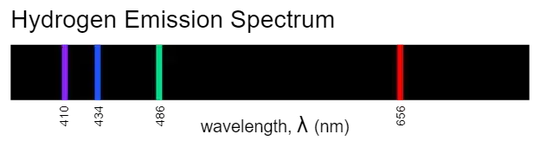

We can also tell that objects are receding at speed proportional to their distance by way of observing their spectra. For example, take hydrogen:

When we take a spectrometer to an atom of hydrogen, which makes up the vast majority of the Universe's mass (the other few elements are stuff like helium and carbon and oxygen and nitrogen, which also all have distinctive spectra), we will always see these exact frequencies. It's just a quantum mechanics thing: a photon with a wavelength of 656 nanometers carries just enough energy to excite a hydrogen atom's electron into one particular excitation state.

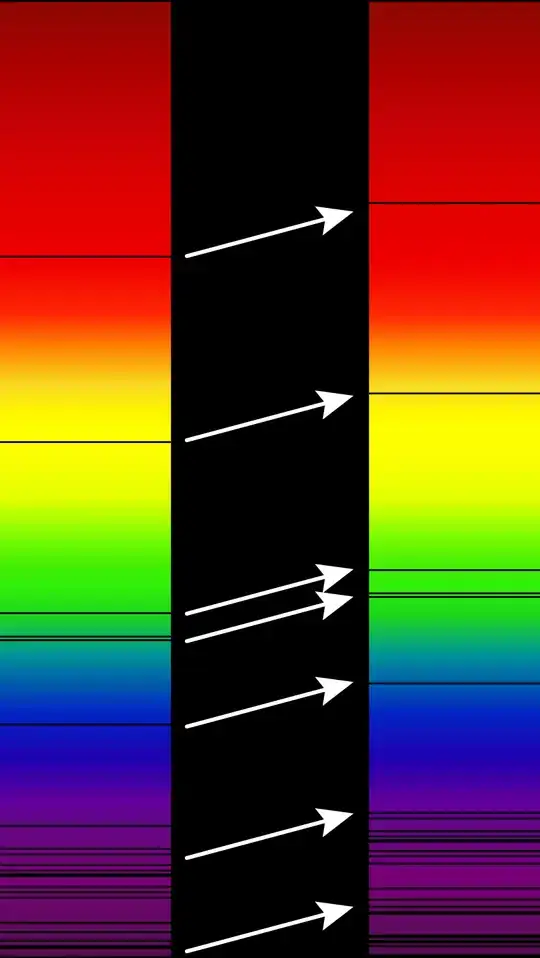

However, when we look at very distant galaxies, we see that these lines appear shifted. This is because the galaxy is moving away from us, and the photon becomes redshifted. For example, look at these two spectra:

The former spectrum is from our Sun, while the latter is from stars in a distant supercluster. The latter appears "moved up" because the galaxies there are moving away from ours at a certain speed, causing their light to redshift by a very specific amount.

What we've observed is that Hubble's Law fits the data: by analyzing the redshift from galaxies at known distances, we can determine the Hubble constant, which is naturally used in Hubble's law, and ascertain that universal expansion is occurring.

- 8,801

In the standard cosmological model (ΛCDM), the expansion of the universe is just the relative motion of the objects in the universe. The redshift is a Doppler shift due to the relative motion, and the distance between the galaxies increases with time as one would expect from relative motion. This model fits all of the data, so by Occam's razor there's no need to suppose that anything more complicated is going on.

It's a misconception that "expansion of space" exists as a separate physical phenomenon from ordinary motion. It's just a different description (in different coordinates) of the same physical phenomenon. See this answer for more information.

- 29,129

I have been trying to understand ... why Hubble's Law needs to implicate any sort of relative motion between galaxies.

First we have to clearly define what we mean by "relative motion". Let's imagine for a moment that we live in the flat non expanding Minkowski space of Special Relativity. a distant rocket traveling at 80% the of the speed of light relative to us would have a redshift factor of $$z = \frac{f_s}{f_o}-1= \sqrt{\frac{c+\beta}{c-\beta}}-1= \sqrt{\frac{1+0.8}{1-0.8}}-1=2$$

where $f_s$ and $f_o$ are the frequency emitted and observed respectively and $\beta$ is the velocity (positive if going away from the observer) of the source relative to the observer (who is assumed to be stationary).

In flat Minkowski space the source is treated as being time dilated due to its velocity relative to the observer and this is taken into account when calculating the relativistic Doppler factor (z) given above. In the curved expanding spacetime used in cosmology, the source only experiences time dilation if it is moving relative to the local spacetime so the classical Doppler equation (which ignores time dilation) is used which is: $$z+1 = \frac{f_s}{f_o} = \frac{(c+\beta)}{c} $$ and solving for the effective relative velocity gives us: $$\beta = c (z + 1)-c $$ and using the observed z factor obtained above $$\beta = c(2+1)-c = 2c.$$

By effective relative velocity, I mean the velocity calculated from the Doppler shift, is what you would obtain, if the emitting object was moving with that velocity in a classical wave medium.

This implies that the object is moving at twice the speed of light relative to us, but this is not an issue, because the receding object is treated as being stationary relative to the local spacetime, and the redshift is attributed to the lengthening of the wavelength due to the expansion of the universe during the travel time of the photon. Note that in cosmology, time dilation (and length contraction) are not a function of the object's velocity relative to the observer ,but are a function of the object's velocity relative to the spacetime in its vicinity. In one interpretation, a distant object in the Hubble flow is stationary in the sense that it is at rest with the local spacetime and does not experience time dilation or length contraction due to its apparent motion relative to the observer. This distant object would actually measure itself to be stationary relative to the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation (CMBR).

In summary it depends what you call the relative motion. We can dismiss thinking of the object as moving at 2c relative to us, because we can catch up with object by always travelling at a velocity that is less than c. That would not be possible if in any way the object was really moving at 2c.What if we laid out a very long massless ruler (massless, because we don't want it to collapse under its self gravitation), all the way to the distant galaxy while keeping the near end stationary WRT the CMBR with thrusters? The distant galaxy would be moving at a velocity of 0.8c relative to the end of the ruler nearest to the galaxy. That is one way of interpreting the meaning of the 0.8c result of using the relativistic version of the Doppler redshift.

- 10,288

So far, since almost a century, the only possible explanation for the cosmological redshift is a Doppler shift. All other explanations have failed. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tired_light.

- 27,443