The only way we can see to the centre of M87 is if the hot gas surrounding it is optically thin and transparent to its own radiation (NB, and see below, it is likely that the M87 black hole does not possess a geometrically thin, optically thick disk as visualised in the movie "Interstellar"). In those circumstances, then the brightness you see along any particular sightline will correspond to the path length through the hot gas. The brightness in any image will depend on how much emitting plasma is enclosed within the boundary of two sightlines separated by the angular resolution of the image.

If you look directly (radially) towards the centre of the black hole, then your sightline traverses through hot has between about $3r_s$ (the innermost stable circular orbit) and you. This is by no means "black", but in comparison to sightlines which pass close to the photon circle at $r=1.5r_s$ (see below), it is dark.

On the other hand, if you are looking at light arriving with an impact parameter of $3 \sqrt{3} r_s/2$ (basically the radius of the bright ring), then that sightline has a closest approach of $\sim 1.5r_s$, may circle around the black hole and pass through considerably more hot gas. In addition, there is a focussing effect whereby sightlines close to (but greater than) this impact parameter can traverse the surrounding gas at almost any angle, meaning that the summation of all those closely packed sightlines appears very bright.

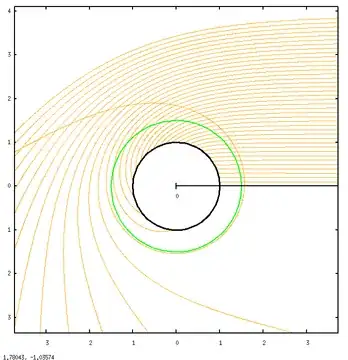

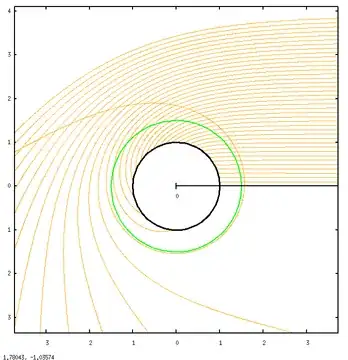

It is very hard to explain without a picture, so here is one I've borrowed that shows some light rays arising from material around the black hole and heading towards an observer (on the right, at infinity).

Any light rays with an impact parameter less than the magic number of $3\sqrt{3}r_s/2$ end up inside the photon sphere at $r=1.5r_s$ (shown in green) and then in the black hole (event horizon is the black circle), so never make it to the observer. The hot gas will only occupy the region further away than $r \sim 3r_s$, which is where the light will originate. You can see there are lots of sightlines encompassing large volumes of emitting material that pass close to $r=1.5r_s$ (but just above) and then end up heading towards the observer with an impact parameter of $3\sqrt{3}r_s/2$ and just above. There are also sightlines directly towards the black hole but these only pass through the material directly in front of the black hole (and at $r>3r_s$) and as a result, this region will appear much fainter.

Edit: It is worth noting that the accretion flow around the black hole is not expected to be in the form of an optically thick, geometrically thin accretion disk - much like that portrayed in the movie "Interstellar" - but a geometrically thick, optically thin (transparent) flow. As the stated in the original Event Horizon Telescope M87 paper:

The simulations of Luminet (1979) showed that for a black

hole embedded in a geometrically thin, optically thick accretion

disk, the photon capture radius would appear to a distant

observer as a thin emission ring inside a lensed image of the

accretion disk. For accreting black holes embedded in a

geometrically thick, optically thin emission region, as in

LLAGNs [low-luminosity active galactic nuclei, like M87], the combination of an event horizon and light

bending leads to the appearance of a dark “shadow” together

with a bright emission ring that should be detectable through

very long baseline interferometery (VLBI) experiments.

In other words, the light coming from around $r=1.5r_s$ is what dominates the image, not the fainter direct light coming from the accretion disk itself. Thus this bright ring morphology would be dominant whatever the orientation of the black hole spin and accretion disk.