You talk about the action of $U$ on $X$, but there are generally many possible actions of a group on itself. These are simply different actions - which one is 'the right one' depends on the circumstances. It's not to do with the type of object you are applying it to, it's about what sort of operation you want to apply. (Like, sometimes you add Real numbers together and sometimes you multiply them. Which is correct?)

Using elements of a group to represent a state is a fairly common manoeuvre. You pick a specific but arbitrary state from the state space to serve as an "origin", and then you apply transformations to it that result in the state being referred to. So Cartesian coordinates can be described as picking an origin point, and then applying successive translations in $x$, $y$, and $z$ directions to reach the point being referred to. Latitude and longitude coordinates on the Earth are implemented by picking an origin point off the coast of Africa, then applying a rotation through the angle of latitude about one axis, then a rotation through the angle of longitude about the polar axis. We are using the transformation to provide coordinates for the state space, but the transformation is not generally the state itself. Sometimes we can ignore the distinction, and sometimes it leads to deep confusion. This is especially true of linear transformations on a vector space, because the transformations themselves constitute a different vector space, which we sometimes use. Real $2 \times 2$ matrices act on a vector space of dimension $2$, but are themselves a vector space of dimension $4$. (The four elements of a $2 \times 2$ matrix can be varied independently.) Even if we restrict the group so the dimensions match (e.g. by just picking unitary or orthogonal matrices), the topology might still be different (e.g. if you use rotations). With spinors, a rotation of angle $\theta$ in one vector space is a rotation of angle $2\theta$ in the other. Be careful.

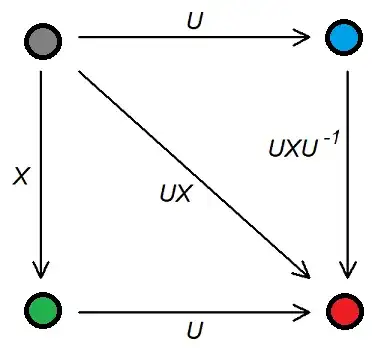

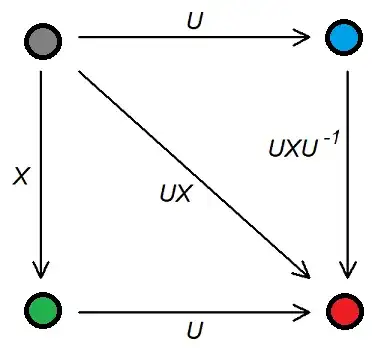

The two different actions above can arise in numerous ways. One way is via a mapping of mappings.

In the diagram, we have a mapping $X$ on the left from grey to green. We map both the start point and the end point using a different mapping $U$, to blue and red respectively. Then there are two mappings that we can describe as the combination of $X$ and $U$. There is the mapping across the diagonal, grey to red, from the original start point to the mapped destination point, which is $UX$. And we have the mapping down the right side of the diagram, blue to red, from the mapped start point to the mapped end point, which is $UXU^{-1}$. This goes round the other three sides, from blue to grey to green to red.

So if we are using $X$ to represent a state by means of its transformation from a fixed "origin" state, then with this interpretation the question is whether we are transforming the state, and the result is a new state relative to the same origin, or whether we are transforming the transformation and the origin doesn't matter. There may be other situations where it arises, and other interpretations. But the basic question is whether you are transforming both input and output of the transformation $X$, or only the output.

The $UXU^{-1}$ operation is called conjugation in group theory, and splits the group into conjugacy classes. It is an inner automorphism of the group, meaning it retains the group structure entirely. This gives it lots of useful properties, with many applications.