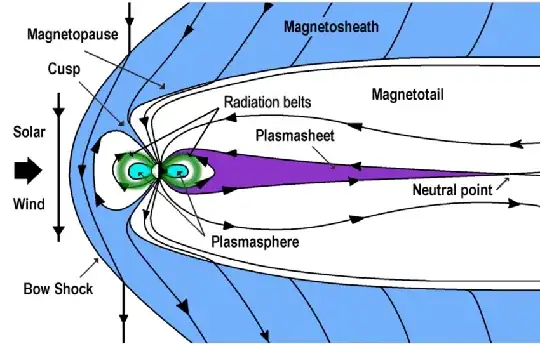

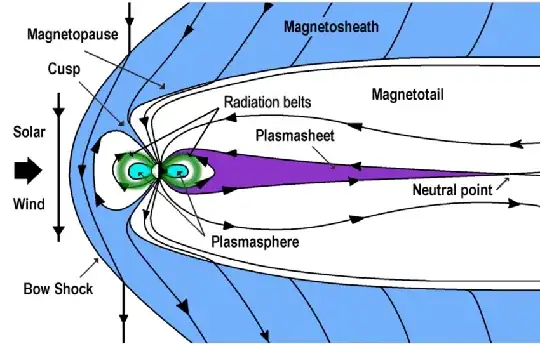

Geomagnetic flux lines originating inside the auroral ovals are dragged by the solar wind to form the outer lobes of the magnetotail and ultimately connect to the interplanetary magnetic field (the IMF) up to many Earth radii downstream. These lines completely bypass the plasma sheet nearer Earth at the core of the magnetotail and thus bypass any electrons the sheet may potentially leak into the field. These lobes contain a much lower concentration of electrons - 20 to 50 times less than the region immediately surrounding the central plasma sheet - and so contribute very little to the aurorae (typically just a faint, diffuse glow in the dark center visible only to instruments).

Fig. 1 - Simplified schematic of Earth's magnetosphere.

Fig. 1 - Simplified schematic of Earth's magnetosphere.

Flux lines originating (that is, exiting Earth's surface) at the auroral oval on the tailward side are stretched to form the inner 'surface' (as it were) of the lobes and thus border the central plasma sheet directly. Electrons from the sheet diffuse into these flux lines. As the lines are progressively stretched tailward, they eventually come together and reconnect near the far end of the plasma sheet, releasing considerable energy.

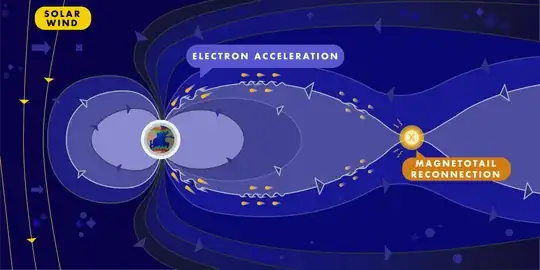

Fig. 2 - Magnetic reconnection.

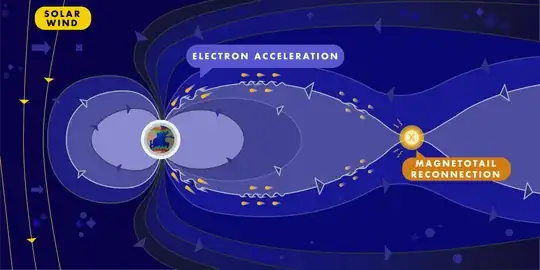

Fig. 2 - Magnetic reconnection.

Upon reconnection, the flux lines rapidly contract Earthward, like a rubber band snapping back from being stretched, launching Alfvén waves that move Earthward along the sheet (their counterpart flux lines likewise snap in the opposite direction, often entraining a bit of plasma sheet and accelerating it - called a 'plasmoid' - tailward). Electrons in the vicinity that already have velocities in the Earthward direction similar to the Alfvén waves' group velocity are snagged and carried along like surfers on a wave, and accelerated by the electric field of the Alfvén waves to energies in the ten keV range (a process called Landau damping). These electrons spiral along the flux lines to the poles, forming a field-aligned current, where they impact Earth's upper atmosphere at around 20,000 km/s, creating auroras. As the flux lines further inside the oval lead elsewhere and so do not participate in this process, there are no auroras there as those lines don't lead to a ready supply of electrons nor the means to accelerate them significantly. This completes the magnetotail side of the auroral oval.

Fig. 3 - Auroral electrons surfing Alfvén waves generated by a magnetic reconnection event.

(note the yellow vertical lines on the left represent the IMF, not the solar wind as labelled in yellow. This label applies to the faint blue arrows beneath pointing to the right. The unfortunate mix of colors makes it a bit confusing.)

Fig. 3 - Auroral electrons surfing Alfvén waves generated by a magnetic reconnection event.

(note the yellow vertical lines on the left represent the IMF, not the solar wind as labelled in yellow. This label applies to the faint blue arrows beneath pointing to the right. The unfortunate mix of colors makes it a bit confusing.)

The weaker, sunward side of the auroral oval is supplied by electrons from the dayside magnetopause which are funneled down through the cusps to the poles along flux lines that intersect the upper atmosphere at the auroral oval. The aurorae on the sunward side of the oval are generally more diffuse than those facing the magnetotail. These electrons are also accelerated by reconnection events, but the picture here is a bit more complicated and beyond the scope of this discussion. Suffice it to say that these events are also a source of accelerated, aurora-bound electrons.

Flux lines originating outside the auroral ovals (that is, lines originating more equatorward) stay relatively close to Earth, within a few Earth radii, and so are largely closed off from sources of auroral electrons. These lines do not participate in auroral processes except during especially strong magnetic storms which can greatly distort the field near Earth.

This is a highly simplified explanation of course, but it does describe in general terms why aurorae tend to form an oval pattern with a dark center. It is these particular sets of flux lines that connect to ready supplies of electrons along with the means to accelerate them poleward.