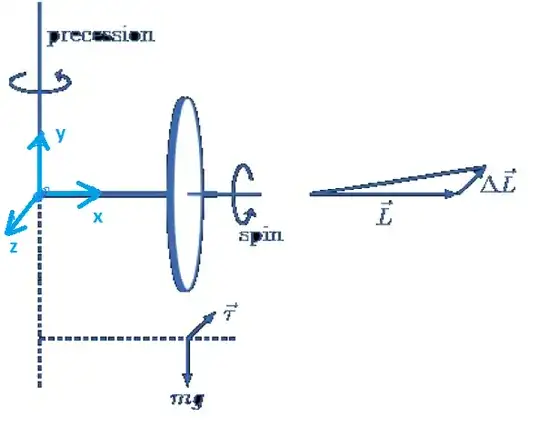

I have a question about the dynamics of a horizontally suspended rotating wheel subjected to the gravitational force, like in the following picture I took from here:

At the beginning, the wheel has an angular momentum $\vec{L}:=L \vec{e_x} $ in the horizontal plane, which coincides with the axis of rotation (considered as the initial condition before the gravitational force starts to act). Then, we let the gravity act on the wheel, and we observe that the wheel axis performs a precession movement on the horizontal plane.

For the sake of completeness, here's a video discussing it.

The theory says that gravity exerts torque $M \vec{e_y}$ (directing into the drawn 2d plane) on the wheel around the mounting point as a fixed point, so that according to the angular momentum law, in an infinitely small period of time $\tau$ the new angular momentum $ L' $ has the value $\vec{L} + \Delta L = \vec{e_x } + \tau \cdot M \vec{e_y} $ also rotates infinitesimally in the horizontal xy plane. That's clear so far.

Question: What I don't understand is why the axis of rotation follows this movement precisely? i.e., tries to align with the direction of the angular momentum evolving directly by gravitational force on the horizontal plane to $\vec{L} \to \vec{L} + \Delta\vec{L}$ as shown in the picture? In general, the angular momentum and the axis of rotation of the considered rigid body are not necessarily parallel. Only if the rotation is about one of its major axes.

So the question is not why the angular momentum moves that way (it's clear to me), but why the angular velocity pseudovector of the wheel "strives" towards this alignment with respect to the direction of the angular momentum? Which principle forces this behaviour?