When two forces act on a point mass,we add the forces like we usually do and i have no problem understanding that. When the same forces are applied on a rigid body,how are we able to add them the same way?

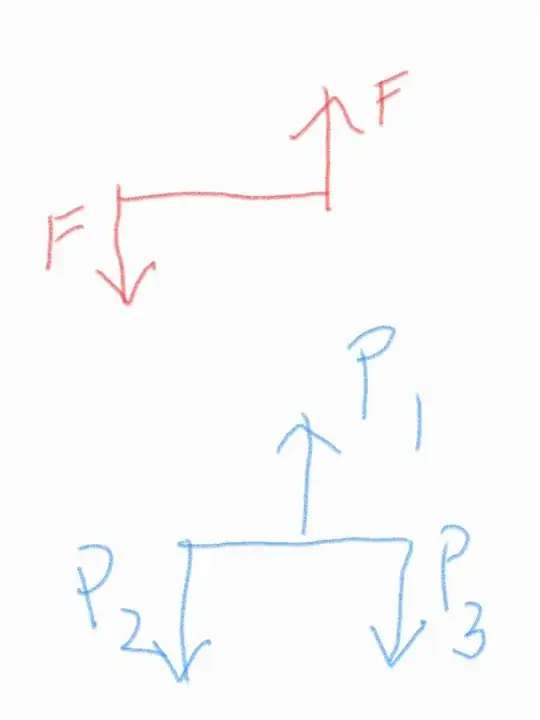

- In the first diagram,what we have is a couple. And almost everywhere it is said that it can only produce rotational motion and no translational motion since opposite forces cancel out. But don't we cancel out opposite forces if they acted on the same particle? What is the proof that we can cancel out forces like this when the scenario is extended to a bigger body? So when doing $F+(-F)=0$ aren't we considering that bigger body as a point particle? I just wanted to know why it is justified to treat the bigger body as a point particle in terms of adding forces.

2)The second diagram is also the same thing. Typically when we say that the extended body is in equilibrium, we at first add the downward forces in $-y$ axis $P_2+P_3$ just as if the bigger body was a point particle,meaning both the forces $P_2$ and $P_3$ are acting at the same point mass. Then we say for equilibrium we need $P_1=P_2+P_3$. I would have no problem admitting these only if it were a point particle instead of an extended body. But i am finding it hard to digest why we can treat the extended body like a point mass while adding forces.

So my main dilemma is to find a proof why we can treat extended objects as if they were point particles while adding forces and also what is the proof that the whole body will experience the same linear effect due to the force which is actually applied at only one certain point of the body.