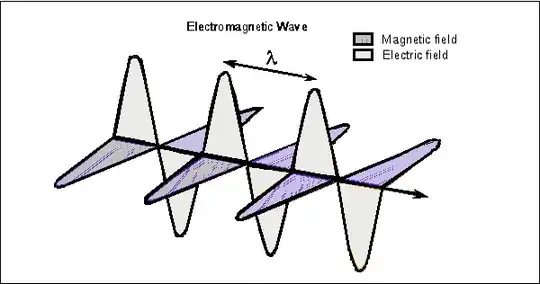

From an Electromagnetic Theory classical standpoint and energy-wise description, form my experience, educationally it is perfectly fine to equalize a single photon with one wavelength period of a Poynting vector of monochromatic light, during its propagation in space.

Since the energy of a single photon is equal with the energy of a single wavelength of monochromatic light consisting from these photons according to the general expression:

$$E_{Ph}=E_{wl}=hc/λ.$$

where $h$, $c$ and $λ$ are the Planck constant , the speed of light in free space and the wavelength of light accordingly.

Notice, the Poynting vector illustration shown in the question's figure could represent a beam of monochromatic light with the photoemitter calibrated to output sequentially an ideally one photon each time. Of course if there are more than one photons output each time then they would stack together and increase the intensity of the beam (i.e. amplitude in the poynting vector shown). But yes, the figure shown assumes one photon is transmitted each time in sequence on the poynting vector.

Sine wave function is 100% compatible with the spin 1 thus 2π-symmetry characteristic of a normal photon. Energy-wise, with the assumption that the amplitude shown in the Poynting vector wave illustration herein corresponds to a single photon each time present in the photon train, the illustration is correct. Surely as an isolated particle the photon is not a sine wave rather a standing wave however its interaction with its environment when propagating through space is as an electromagnetic sine wave. The later is exactly what this Poynting vector is showing.

Also, to complete the above Poynting vector educational representation of a single photon of monochromatic light propagating through space with $c$ speed and say of angular frequency $ω$ in rad/s shown in the question's figure above, we must be able to calculate the Poynting vector amplitude (i.e. intensity of single photon of monochromatic light of a given frequency).

"The magnitude of amplitude of the Poynting vector (energy flow) of the photon is:

$$

\mathscr{P}_0=\varepsilon_0 c E_0^2=\hbar \omega^4 / 4 \pi \alpha c^2

$$

Where, $\hbar$ is the reduced Planck Constant and $α$ the Fine Structure Constant" [1].